Yesterday: ‘The Pepsoidal Fall: Pepsi & Teleoplexy’

DAY 2. Crystal Pepsi / Crystal Hyaline: or, How to See with your Gut

Pepsi invents itself from the future. The retrochronic force of these convergences-effects are registered as ripples — surface currents — in the poesy of a blind, seventeenth-century Christian prophet. Sing, sugar-infused Muse!

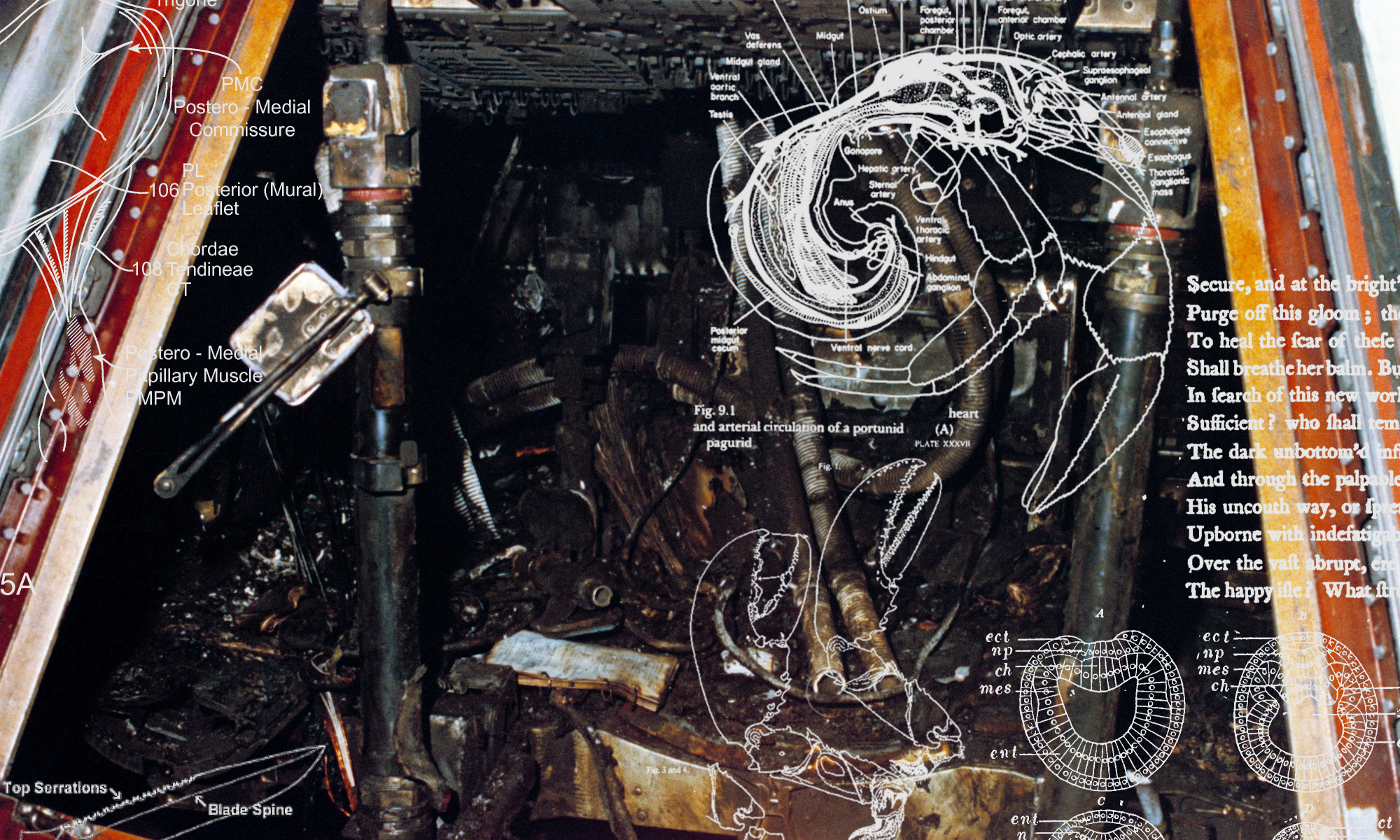

In the early 1990s PepsiCo introduced a colourless form of its now infamous soft drink, which sold under the name Crystal Pepsi. Following from a contemporary marketing fad geared towards selling transparent or colourless editions of familiar products (initiated by Ivory soap), the proviso was that transparency would evoke in consumers positive notions of ‘cleanness’ or ‘clarity’. Crystal Pepsi, however, was a market failure.[note]T. Triplett, ‘Consumers Show Little Taste for Clear Beverages’, in Marketing News, vol.28, no.11, (1994), 1-2.[/note] (The relentless juggernaut of nostalgia has recently resurrected it from limbo, however.) It seems, then, that in our fallen (capitalised) state we actually desire tartareous muck over any vitreous and crystalline elixir. Indeed, advertisers have since retroactively divined that Crystal Pepsi was a failure because consumers were disturbed by the unseemly conjunction of pellucid, heavenly aesthetics with saccharine, voluptuous taste.[note]L.L. Garber Jr. & E.M. Hyatt, ‘Color as a Tool for Visual Persuasion’, in Visual Persuasion. eds. R. Batra & L. Scott (Lawrence Erlbaum, 2000)[/note] Pepsi suits its blackness irrepressibly: as the cheerleader for Capital’s forces of terrestrial obscurity and liquidation, it inevitably and necessarily announces itself ocularly with the skotison of effervescing, liquid blackness.[note]Skotison, originally a rhetorical term, is an invocation and imperative towards darkening. To translate literally, skotison means “darken it!”.[/note] Ontological blackening demands the aesthetics to match: it seems, at the very least, that we subconsciously expect this to be the case (and, insofar as the crystalline marketing experiment therefore failed, our aesthetic-gastric sensibilities tend towards making this a reality). We get the blackness we desire.[note]In this sense, Crystal Pepsi was predestined to fail: accordingly, a ‘suprapepsarian’ reading of consumer ontology and market soteriology invites itself.[/note] The heavenly, vitreous Crystal Pepsi rebounds from our fallen tastebuds: we expect tartar to taste accordingly. Our gullets — like our sinful wills — clamour for nigredo rather than albedo. The Crystal was just too heavenly, too painfully pre-lapsarian. Indeed, the connection of ‘crystal’ with pre-lapsarian perspicuity is — long prior to the modern machinations of PepsiCo marketing psychomancy — a venerable aesthetic collocation. (PepsiCo was only trying to retrospectively capitalise on this: a failed trick to sell post-lapsarian tar as pre-lapsarian philtre.) From Milton’s Paradise Lost:

Witness this new-made world, another Heaven

From Heaven-gate not far, founded in view

Of the clear hyaline, the glassy sea. [PL; vii.617-9]

Here Milton describes the freshly created world by comparing it to the “clear” and “glassy” spheres of outer heaven, as depicted in pre-Copernican and Biblical cosmology. Our “pendant” planet reflects the highest cosmic realms in their shared crystal appearance: the Earth is “founded in view” of these glassy spheres, and they resonate together — in crystalloid harmony — in their new-made cosmic clarity. Specifically, the “hyaline”[note]A nominalized adjective, denoting crystallific nature. See below for more.[/note] described here denotes the “waters above the Firmament” of Genesis 1:6-7.

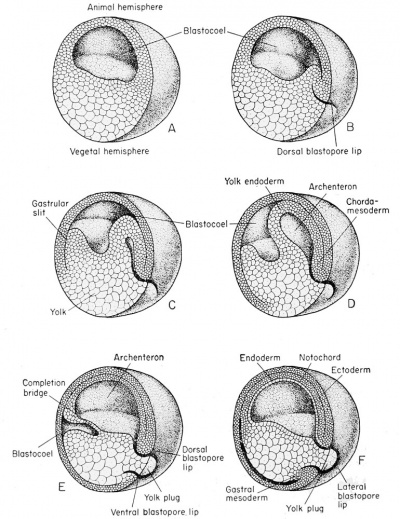

Biblical cosmogony pictures a watery creation whereby God initiates a world-generating and oceanic separation between an originary supernal sea (the “hyaline”) and the derivative sublunary spheres (our cosmos).[note]“And God said, Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters” & “And God made the firmament, and divded the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament: and it was so.”[/note] This hydraulic cosmogony serves to individuate the creation via God’s act of filtration, separating ‘above’ from ‘below’, but it also serves to retain an analogical (placental) connection between these two separated realms (exploiting the fact that they are made from the same, pellucid, medium). This is poetically instanced by the symbolic resonance between what Milton, lines later, calls the “nether ocean” here on Earth, and the original “crystalline ocean” that circumscribes (“circumfus’d”) the entire cosmos [PL; vii.624, vii.271]. The cosmos is separate from (in a derivative sense) but also contained by this thalassal ur-ocean (much as the ‘individual I’ stands in relation to the ‘absolute I’). As a “bright sea” of “jasper” and “liquid pearl” above the outer firmament [PL; iii.484], this cosmic crystal-ball therefore englobes the created universe at the outer limit of its nine concentric spheres, and, in line with Genesis, it is through this supernal sea that Milton’s God is witnessed as having precipitated the universe with “waters beneath from those above dividing” [PL; vii.261-75]. It is through the establishment of this individuating outer boundary, or limit, that the ordered cosmos is separated from the surrounding medium of Chaos: the establishment of this “hyaline” represents the blastulation of the universe.[note] [/note] Milton describes how God “as with a mantle did invest / The rising world of water dark and deep, / Won from the void and formless infinite”: he provides it with a protective skin, a form-suffusing “mantle”. As such, through wrapping the entire created universe in a “clear” liquid sack, this “crystalline ocean” becomes purposed with protecting the cosmos from the “loud misrule” of the Chaos that lies just beyond it [PL; vii.269, vii.271].[note]Chaos is, thus, analogical to the ‘energetic excess’ that Freud describes as facilitating the epithelial individuation of the originary vesicle, in his account of metapsychological abiogenesis, in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (Penguin, 2003).[/note] It is therefore a prophylaxis against an external chaoticism, and — as such — a spheroid cosmic immune system and metaphysical life support.[note]Cf. Peter Sloterdijk, Globes: Macrospherology, Volume II: Spheres (Semiotexte, 2014).[/note] A crystallic womb. Certainly, pre-Copernican cosmology is precisely a cosmology of ‘immuno-containment’, and containment takes place across similar mediums (containment implies infinite divisibility); thus, to stress the ‘containment’ of the sublunary within the “hyaline”, as Milton does, is to impart some of the latter’s “crystalline” perfection to our own world. In other words, through its vitreous dialysis, this primum mobile acts as a vesicle purposed with separating Creation from Chaos: the happy harmony of this amniotic encasement — a placental harmony, therefore, between sublunary fundament and crystalline firmament and achieved through the shared medium of crystal perspicuity — announces the pre-lapsarian stability of Paradise Lost’s “new-made world”. Nonetheless: just as there was something wrong at the heart of the Crystal Pepsi venture, predestining it to fall, so too is there a blackening necrosis within this pellucid womb of Milton’s fictional cosmos.

[/note] Milton describes how God “as with a mantle did invest / The rising world of water dark and deep, / Won from the void and formless infinite”: he provides it with a protective skin, a form-suffusing “mantle”. As such, through wrapping the entire created universe in a “clear” liquid sack, this “crystalline ocean” becomes purposed with protecting the cosmos from the “loud misrule” of the Chaos that lies just beyond it [PL; vii.269, vii.271].[note]Chaos is, thus, analogical to the ‘energetic excess’ that Freud describes as facilitating the epithelial individuation of the originary vesicle, in his account of metapsychological abiogenesis, in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (Penguin, 2003).[/note] It is therefore a prophylaxis against an external chaoticism, and — as such — a spheroid cosmic immune system and metaphysical life support.[note]Cf. Peter Sloterdijk, Globes: Macrospherology, Volume II: Spheres (Semiotexte, 2014).[/note] A crystallic womb. Certainly, pre-Copernican cosmology is precisely a cosmology of ‘immuno-containment’, and containment takes place across similar mediums (containment implies infinite divisibility); thus, to stress the ‘containment’ of the sublunary within the “hyaline”, as Milton does, is to impart some of the latter’s “crystalline” perfection to our own world. In other words, through its vitreous dialysis, this primum mobile acts as a vesicle purposed with separating Creation from Chaos: the happy harmony of this amniotic encasement — a placental harmony, therefore, between sublunary fundament and crystalline firmament and achieved through the shared medium of crystal perspicuity — announces the pre-lapsarian stability of Paradise Lost’s “new-made world”. Nonetheless: just as there was something wrong at the heart of the Crystal Pepsi venture, predestining it to fall, so too is there a blackening necrosis within this pellucid womb of Milton’s fictional cosmos.

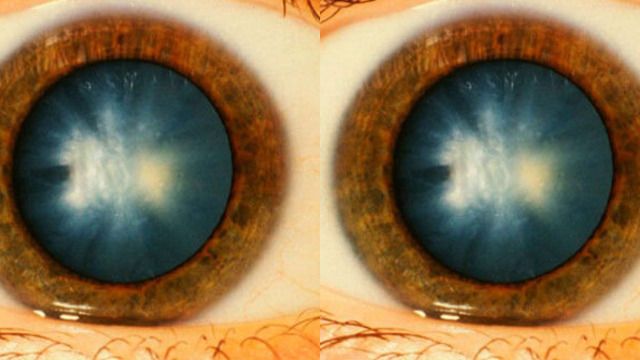

We do not live in a “new-made world” or “another heaven” — and neither did Milton. “The world wears, as it grows”, and crystal turns to cataract, water to pepsi, albedo to nigredo. Indeed, Milton lived in a thoroughly fallen universe: one of gargantuan political, theological, and philosophical upheaval. Witnessing the only military coup d’état in English history, residing in a London under siege, experiencing the divine trauma of regicide, Milton would have likewise passed among not only Arminians and Calvinists, but also Baptists, Diggers, Behmenists, Socinians, Fifth Monarchists, Quakers, Muggletonians, and Levellers. These groups represent the anomalocaris, the oppabinia, and the hallucigenia of Protestant cladistics. It was an intellectual historical explosion of tumultuous size. Certainly, legislative events like the ‘1650 Act against Atheistical, Blasphemous & Excreable Opinion’ evidence this: a response to sectarianism and intestine strife that — unlike any cosmo-hyaline immune system — arise as reactionary rather than prophylactic. The rot was already inside. Madness ensued. In 1656, James Nayler rode into Bristol on an ass attempting to replay Jesus’s arrival in Jerusalem; men like John Pordage — believing themselves daily in “visible communion with angels” — conversed with those like Thomas Tany, who was convinced that he had found cherubs and demons living inside of “vegetables”; and men like Abiezer Coppe, gripped by the conviction that seraphim walked amongst us, inspired sexual radicalism and licentiousness among his admirers. Indeed, the so-called Ranters — with whom Coppe was affiliated — promoted a proto-Sadean and proto-anarchist vision of a sacral sexuality that sought to deify the individual through a nihilistic vision of the unrelenting omnipotence of sovereign selfhood and summit experience. Perceiving all law and morality as limits to freedom, they sought to emulate the ultimate freedom of omnipotent divinity by stripping away from themselves all such legalistic limits to their behavior: nevertheless, they were wise enough to prophesy that doing this successfully would also be a form of self-annihilation (because all personal identity and subjectivity is inextricably couched in normative understanding). They indulged in the so-called antinomian heresy, believing that one could literally become God through the breakdown of all moral structure and limitation: henosis with the divine was achieved not through subservience but, rather, through emulating His crushing omnipotent freedom, transcending all suppressive notions of ‘Good’ and ‘Evil’.[note]As Cohn has identified in The Pursuit of Millenium (OUP, 1970), they were thus a continuation of the late-medieval Brethren of the Free Spirit. Pettman, in After the Orgy (SUNY, 2012), has recently concatenated these earlier upswells of rapturous rupture into a lineage stretching down towards Bataille and Y2K apocalypticism.[/note] A kind of sacral and divine libertinage. This led to orgiastic worship, outrageous voluptuosity, and public nudity. Milton himself was only a few steps removed from such ideologies: he was close to Roger Williams, a proponent of radical toleration, who was, in turn, affiliated with Anne Hutchinson, the centre of a famous antinomian controversy. Put simply, Milton moved through heterodox[note]J. Mueller, ‘Milton on Heresy’, in Milton and Heresy, ed. S.B. Dobranski & J.P. Rumrich (CUP, 1998), 21-38.[/note] and revolutionary times and idea-formations; his own cosmos was by no means perspicuous or “hyaline”.[note]Against the servile, genuflecting readings emanating from the Milton constructed by C.S. Lewis and his followers (the ‘neo-Christians’, as Empson called them, and their ‘invented Milton’, a Milton cleansed of any doctrinal aberrations and radical heterodoxies), we promote — to the point of remedial ‘invention’ — the possibility of a heretical Milton. We know, indeed, that Milton was very much aware of the Greek root of haîresis: which he deems not “of evil note, meaning only the choise […] of any opinion good or bad in religion or any other learning” [A Treatise of Civil Power in Ecclesiastical Causes, vol.vi of The Works of John Milton, ed. F.A. Patterson (Columbia University Press, 1931), 11]. Following this justification, he would variously defend the idea of the free-thinking individual: from the seraph Abdiel (who stands alone, in radical free conscience, as arbiter against Satan’s actions) to Galileo (lionized as “prisoner to the Inquisition [for] thinking […] otherwise then the [orthodox] thought”) [Areopagitica, in vol.iv of Ibid., 330.].[/note]

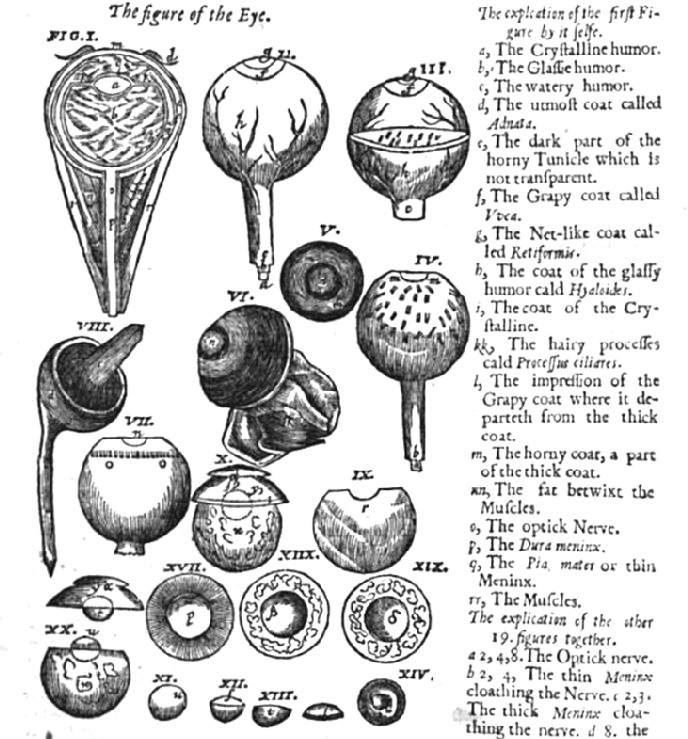

“Hyaline” itself is an intriguing word. It is Milton’s transliteration from Greek, appearing to be the first use of the word as such in English (in prior print it appears, notably, only in the dictionary written by Milton’s nephew, Edward Phillips[note]Edward Phillips, The New World of English Worlds, or, a General Dictionary (London, 1658)[/note], before later appearing in Blount’s 1661 revision of Glossographia.[note]J. Blount, Glossographia; or, a Dictionary Interpreting the Hard Words of Whatsoever Language, Now Used in our Refined English Tongue (London, 1661).[/note] Milton, in the passage quoted above, goes out of his way to inmmediately gloss the word with the phrase “glassy sea”; nevertheless, readers would have likely already inferred the word’s denotation via cognates that where in contemporary circulation. Whilst most editors only note the Greek source-word (ὑάλινος) and its appearance in the Greek bible signifying ‘glassy’ or ‘vitreous’ (it is used to describe the “thalassa hyaline”, or crystal sea, at Rev. 4:6), we also point out the connection to the cognate Greek ὑαλοειδής: which was transliterated as ‘hyaloides’ and referred, in contemporaneous medicine, to the vitreous humours of the eyeball’s lens. Certainly, ‘hyaloides’ had been circulating in English as a medical term for decades before Milton’s writing. Denoting the eye’s vitreous layer, it is significant that Milton also describes the firmament as “vitreous”: moreover, alongside the “vitreous” humour, the eye was also said to contain “crystalline” and “aqueous” humours, which, again, are all adjectives Milton grants to his firmament. Accordingly, it is no surprise that eyeballs in Paradise Lost and other works redound in the same qualities as the “hyaline” ocean above: “enamell’d eyes”[note]Lycidas (ll.139) in Milton: The Complete Shorter Poems, ed. J. Carey (Longman, 2007).[/note], tears of “crystal sluice”[PL; v.113], “liquid notes” from “the eye of the day”[note]’Sonnet I’ (ll.5) in Milton: The Complete Shorter Poems, ed. J. Carey (Longman, 2007).[/note], even “carbuncle” eyes all appear [PL; ix.1500]. Again: as the Earth’s oceans reflect the primum mobile, so too — at an even smaller scale — do our eyes: microcosm and macrocosm, in clear concord. The correspondence goes both ways, however, as cosmic bodies themselves become ocular: the sun is the “eye” of this “great world” [PL; v.171] and the stars are designated as heaven’s “eyes” [PL; v.44]. Furthermore, Jesus’s chariot is said to be “set with eyes” [PL; vi.755]. These eyes are not only described as a litany of gemstones (ὑαλοειδής/hyaloides also signifying “precious stone”), but they are also linked with the “crystal firmament” above (itself adorned with “living sapphires” [PL; iv.605]). This mineral-ocular train is, indeed, described as a “panoply” (likely referring to Argus Panoptes, the many-eyed giant of Greek mythology[note] [/note]). Just as the planets are ‘contained’ within the life-support of the supernal realm, so too are our bodies, vouchsafed via the microcosm-macrocosm concordance of eyeball and firmament. ‘[T]here is a double firmament, one in the heavens and one in each body, and these are linked by mutual concordance’[note]Walter Pagel, Joan Baptista Van Helmont: Reformer of Science and Medicine (CUP, 2002), 99.[/note] This semantic entanglement between eyeball-strcuture and cosmos-structure is, unsurprisingly, ancient. As the Talmud, which Milton was familiar with, puts it:

[/note]). Just as the planets are ‘contained’ within the life-support of the supernal realm, so too are our bodies, vouchsafed via the microcosm-macrocosm concordance of eyeball and firmament. ‘[T]here is a double firmament, one in the heavens and one in each body, and these are linked by mutual concordance’[note]Walter Pagel, Joan Baptista Van Helmont: Reformer of Science and Medicine (CUP, 2002), 99.[/note] This semantic entanglement between eyeball-strcuture and cosmos-structure is, unsurprisingly, ancient. As the Talmud, which Milton was familiar with, puts it:

This world is like a human eyeball. The white in it is like the ocean, which surrounded the whole world. The black in it is the world itself.[note]Zohar, the Book of Enlightenment, ed. Daniel Chanan Matt (Paulist, 1983), 243.[/note]

Milton, moreover, would have been aware of the influence this ancient mystical heritage exerted upon the verbiage of contemporary ophthalmic anatomy (i.e. the derivation of ‘hyaloides’ from ‘hyaline’). Engaging in “perpetual tampering with physic”[note]Edward Phillips, Life of Milton (London, 1694).[/note], Milton, for obvious reasons, will have thoroughly investigated medical material surrounding eyes. Indeed, Milton would have been specifically motivated to research the hyaloides in particular.

Deep under ground, materials dark and crude,

Of spirituous and fiery spume,

[…]

These in their dark nativity the deep

Shall yield to us, pregnant with infernal flame, [PL; vi.478-83]

In 1645, Milton delineates the onset of his blindness in a letter to be passed to the French opthamologist François Thévenin, via Leonard Philaris. “It is ten years,” he writes,

more or less, since I noticed my sight becoming weak and growing dim, and at the same time my spleen and all my viscera burdened and shaken with flatulence.[note]John Milton, The Complete Prose Works, ed. D. Wolfe, vol.iv (Oxford University Press, 1966), 867-71.[/note]

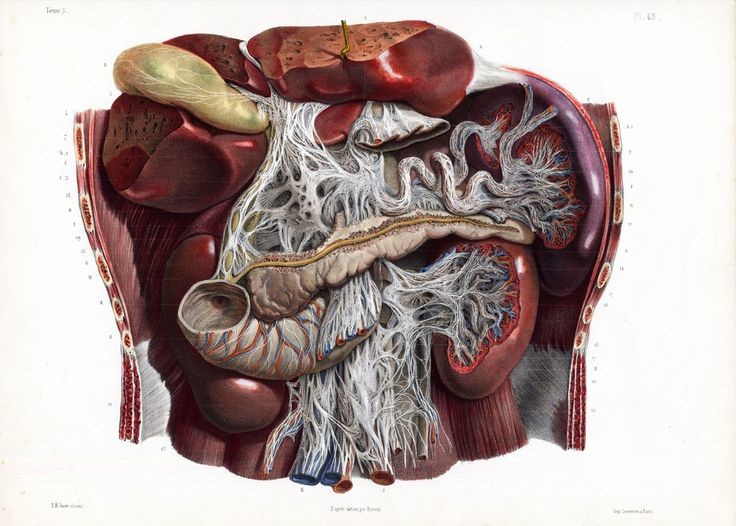

Milton links the eye’s failing sight to the gut’s failing digestion: “flatibusqe vexari”, as he puts it in the original Latin. The ocular “vapores” occur “a cibo præsertim” he reports, meaning that they occur after eating. Indeed, the contemporaneous medical wisdom had it that the aetiology behind the denaturation of the hyaloides in gutta serena was precisely ‘ill digestion’.[note]Kerrigan, W. The Sacred Complex: On the Pyschogenesis of Paradise Lost (Harvard University Press, 1983), 203.[/note] Ill digestion causes blindness.

Milton frequently connects digestion with perception. Both processes arise as the subject’s integration of external modalities: they are both forms of navigating within an external world. And — identically for both — this ‘assimilation’ can proceed with more or less success. The disruption of one results in blindness; the disruption of the other results in indigestion. Failing sight is failure to behold the ocular world; failing digestion is failure to behold the culinary world. As Milton puts it: to be “exiled from light” is to be pushed to “the land of darkness”; whilst, correlatively, “nourishment” that is not properly digestion leads to “wind”. Both arise as problems of incorporation or integration with the world. As Nietzsche so wisely said, “truly, my brothers, the soul is a stomach!”. Just as the deposition of a gut wall is what individuates the organism as a self-enclosed energetic economy, we likewise observe that the later generation of transcendental categories (as a productive conceptual limit, aping the metabolic limit entrenched by the archenteron) identically provides the enclosure of finitude that marks out, and thus potentiates, the subject as an attentional economy.[note]Concepts and language provide the special envelope that marks out or delimits the reasoning subject. In Book IV, Eve experiences this by looking at her own reflection, which splits her in two, encasing her in self-representation. She recalls, “I first awak’t […] wondering where / And what I was” [iv.450-2]. Soon she finds the answer: “With unexperienced thought / As I bent down to look, just opposite, / A shape within the watery gleam appeared / Bending to look on me, I started back, / It started back, but pleased I soon returned” [iv.457-63]. An image of herself allows her to ‘see’ herself, becoming thus ‘self-conscious’, but only through means that are external to her, separating her from herself, providing reflexivity only through mediation. Conceptual language is the prime form of mediation (which finds its literalization in the watery mirror deployed here), and in that provides the protective shell (by allowing for the ‘cut’ in continuity) within which a self-conscious subject can emerge.[/note] By schismatically incising a boundary in continuity, both finitude-generating blockages potentiate the individual as individual, providing a self-infolding block that empowers selective navigation of modalities, a separation that — in turn — feeds back into itself and becomes self-deepening. Concepts are the epithelium or gut wall of the transcendental ego (language acquisition is thus transcendental enterocoely). Either way, be it in splanchnogenesis or noogenesis, organismic finitude is generated by an enfolding and englobement: either within concepts or within abdominal cavities. The sphere of the transcendental was preceded by the sphere of the coelom (the endodermal layer that folds into a gut in all organisms exhibiting the complex internal differentiation required for the dynamism of digestive metabolism). Indeed, the interface chauvinism — possibly unique to us as bilaterally symmetric animals — which presumes that CNS-derived world-interfaces (the electric vagaries attendant upon congeries of overgrown ganglia) are the only ways we locomote the world forgets this enveloping gastric ur-relation, which functionally enveloped all forms of representative interface up until very recently, when intelligence lifted off from this its functional substrate and into its own self-selecting auto-catalysis.

Milton, on the contrary, did not forget this: he was acutely sensitive to it. Indeed, he couldn’t not be — even if he wanted to — because his own viscera were so violently wracked with “flatibus”. Accordingly, deeply aware of the quasi-transcendental entanglements of the alimentary and the perceptual, Milton’s Raphael — in his angelic wisdom — pronounces that “[k]nowledge is as food” [PL; vii.126] and he explains that, just as “[w]isdom” leads to “nourishment”, “folly” leads to “wind” [PL; vii.130]. To quote in full:

But Knowledge is as food, and needs no less

Her Temperance over appetite, to know

In measure what the mind may well contain;

Oppresses else with surfeit, and soon turns

Wisdom to folly, as nourishment to wind. [PL; vii.126-30]

Such intertwining of digestive and epistemic assimilation — and “Temperance” likewise — makes perfect sense in a story centring around Eve’s consumption of the apple: which itself is, of course, as Milton stresses “intellectual food” [PL; xi.768]. So, just as folly leads to wind, the acquisition of the forbidden knowledge encrypted deep within the apple leads directly to cosmological indigestion and the depuration of the whole of nature illustrated in the Fall. The Fall affects everything, not only is the ground “Cursed… for thy sake” [PL; x.201], as Jesus proclaims to Adam (Milton here lifting the wording straight from the King James Bible). Indeed, only a couple of decades after Paradise Lost, Thomas Burnet wrote his physico-theological tract entitled Telluris Theoria Sacra (which, later on, Coleridge liked to compare to Paradise Lost), in which he recounted how the entire planet itself had been geometrically ‘perfect’ prior to the Fall — that is, entirely smooth, totally spherical — and it was the entry of Sin into the world that had thrown up the mountains, the crags, and the jagged and broken aspect of our post-lapsarian world. Such orogenic harmatiology is presaged by Milton, who writes that, upon Eve’s ingestion of knowledge,

Earth felt the wound, and Nature from her seat,

Sighing through all her works, gave signs of woe. [PL; ix.782-3]

The ingestion, via “intellectual food”, of knowledge into the world — as the ability to be Wrong or Right — gives nature itself chronic indigestion. If “[s]ighing” from “her seat” was not enough to alert us to the fact that the entire planet is farting, Milton immediately hammers the point home:

Earth trembled from her entrails, as again

In pangs, and Nature gave a second groan [PL; ix.1000-1]

Because knowledge of Good and Evil introduces the capacity for being Right or Wrong, so too does it generate the capacity for digestion or indigestion (in affairs both alimentary and epistemic). And so, again, just as “folly” leads to “wind”, the original formation of epistemic fallibility is signposted and announced by nature itself as the very planet lets off two volleys of tortured “flatibus”, trembling “from her entrails”. (An indigestion that, for Burnet, was registered in the crumpling of the earth’s skeleton into mountainous ruins.) The birth of epistemology is the birth of metabolism, for both are — essentially — the same thing. With fallibility comes excrement. In Lycidas, Milton would talk of the sheep (allegorical placeholders for the Christian flock) who, fed with theological blunders by irresponsible prelates, become “swol’n with wind” and “Rot inwardly” upon knowing wrongly, spreading “foul contagion”.[note]Lycidas, ll.125-7.[/note] Nutrition fails in expulsion, thus ignorance and falseness lead to intellectual vomiting or epistemic diarrhoea: in his antiprelatical Of Reformation, Milton thus singles out “the new-vomited Paganisme of sensuall Idolatry”.[note]John Milton, Of Reformation, in Complete Works of John Milton, ed. Don M. Wolfe (Yale University Press, 1966), 1:519-20.[/note] Epistemology, through the poet’s writing, is entrenched — again and again — as a deeply metabolic endeavour. Thus, it becomes a civic duty to keep a good diet in nutritive and noetic matters.

Accordingly, Milton-the-propagandist would promote “the right possessing” of the body in “Diet or Abstinence” in order to render “it more pliant [and] useful to the Common-wealth”.[note]John Milton, The Reason of Church Government Urged Against Prelaty, in vol.iii of The Works of John Milton, ed. F.A. Patterson (Columbia University Press, 1931), 187.[/note] Similarly, the “abatement of a full diet” can stave off unwanted sexual desires.[note]John Milton, Doctrine & Discipline of Divorce, in vol.iii of The Works of John Milton, ed. F.A. Patterson (Columbia University Press, 1931), 308-10.[/note] It should come as no surprise, then, that nutrition and consumption has been deemed the ‘central animating metaphor’ for the discussion of knowledge-economy in Areopagitica.[note]N. Smith, ‘Areopagitica: Voicing Contexts, 1643-5′, in Politics, Poetics, and Hermeneutics in Milton’s Prose, ed. D. Loewenstein & J.G. Turner (CUP, 1990), 109.[/note] Defending “the Liberty of Unlicenc’d Printing”, this influential pamphlet is riddled with metabolic-epistemology, centred around the hooking up of eating habits to reading habits, and deploying this as a prime heuristic in Milton’s argument contra censorship. “[T]o the pure all things are pure”, Milton decrees. This applies not only to “meats and drinks”, but also — naturally — to “knowledge”.[note]Areopagitica, 308-9.[/note] Epistemology is metabolism, and metabolism epistemology. He is claiming here that assimilation or indigestion rest primarily upon the moral character of the imbiber (thus, if a readership is ‘good’ it should be able to consume morally putrescent ideas without risk of corruption). To the sinful, everything leads to “wind”; to the pious, everything is “nourishment”. As “wholesome meats to a vitiated stomack differ little or nothing from unwholesome”, so too — correlatively — do pure ideas become flatus to compromised minds. Because the opposite therefore also holds (i.e. an unvitiated stomach can safely handle rotten ideas), Milton argues for a free press and free circulation of mental ‘nourishment’. The negative effects of a heterodox diet of books would only be felt by people already spiritually or morally compromised:

When God did enlarge the universal diet of man’s body, [he] then also, as before, left arbitrary the dyeting and repasting of our minds; as wherein every mature man might have to exercise his owne leading capacity.[note]Areopagitica, 308-9.[/note]

This subjectivist account of digestion is part and parcel with the central place of free will in all of Milton’s philosophy. Again, it stresses the fact that indigestion is — therefore — a result of the entrance of the choice between good and evil into the world: indigestion is a thoroughly post-lapsarian affair. Before the Fall, there was — ontologically — no such thing as tummy ache (and, accordingly, Paradise Lost would go on to stress digestive ailments as particularly emblematic afflictions of our postlasped pathology). Yet, by connecting digestion so thoroughly with free will, Milton implicitly sets up a model of perfect assimilation as symptom of moral perfection. Good digestion is the model of good civic understanding, and vice versa. As such, just as the model and ideal of cognitive apprehension is total understanding, so too would the model and ideal of digestion be one of total metabolic assimilation, of 100% digestive efficiency. In this perfect digestive tract, no “meats” could resist incorporation, no recalcitrance would arise from ingested matter, all items would be fully absorbed (thus, no excrement). The meat would become whatever the consumer chooses (again, “to the pure all things are pure”). Indeed, if it is possible that man’s understanding could overcome the boundaries of post-lapsarian finitude, would it not also make sense that man’s stomach could overcome the resistance of fallen foodstuffs? If man’s “glassy essence” can be utterly devoid of dioptrics, can not man’s “dyeting” be devoid of putrescence and excrement? Can we aspire to crystalline perspicuity in both our cognitive and our gastric “dyeting”? Can we stop desiring sugary blackness and return to pre-lapsarian vitreosity? Certainly, images of a state of crystalline epistemic concord do occur in Milton: moments where experience is ‘digested’ perfectly, so to speak. Accordingly, in ‘Prolusion III’, a young Milton had written that the “mind should not consent to be limited and circumscribed by the earth’s boundaries, but should range beyond the confines of the world”[note]John Milton, ‘Prolusion III’, ll.171, in vol.xii of The Works of John Milton, ed. F.A. Patterson (Columbia University Press, 1931)[/note] and, in ‘Elegy V’, the narrator writes that his “mind is whirled up to the height of the bright, clear sky: freedom from my body”.[note]John Milton, ‘Elegy V’, ll.15-20, in Milton: The Complete Shorter Poems, ed. J. Carey (Longman, 2007). Carey’s translation from the Latin is used here.[/note] It is even claimed here that the “unseen depths of Tartarus do not escape my eyes”. That is, in this state of perceptive-concord, even darkness is eliminated from perspectival perspicuity (just as, presumably, pre-lapsarian digestion would eliminate the need for excretion). (Note, moreover, that Milton deploys the words “liquidi raptatur” to describe this ascent: his “mind’s eye” becomes fully aqueous like the firmament; and, hence, his intellect resembles the “clear hyaline”; ocular recalcitrance evaporates.) Consequently, unlike an alimentary canal that excretes, an eye that fails to see with clarity, or a mind that pierces the “innermost sanctuaries”, Milton here hints towards the potential for subjects in pure accord with the Outside. Relinquished of the complications of excess matter, there are no cataracts, nor any indigestions. Nothing can exceed this ideal subject; it experiences epistemological eupepsia. As his years lengthened, however, and he grew older, the reality, for Milton, could not have been more different: vexed by flatibus, tortured by internal putrescence, and quaking with dyspepsia. Just as Crystal Pepsi’s attempt at perspicuity collapsed back into sugary nigredo, so too did Milton’s dreams of perfect epistemic-metabolic assimilation crumple into flatulent darkness. Man’s “glassy essence” denatures into excremental occlusion, as chaotic Pepsi — avatar for desiring-revolution — comes to invade it.

Tomorrow: ‘Peristaltic Metaphysics and the Invention of Pepsi’