Yesterday: ‘Sugar & Zero, Milton & Böhme: the Dyspeptic Abyss of Theogony’

THE FINAL DAY. 𝕯𝖊𝖘𝖈𝖊𝖓𝖘𝖚𝖘 𝖆𝖉 𝕴𝖓𝖋𝖊𝖗𝖔𝖘: or, My Belly Consumed My Head

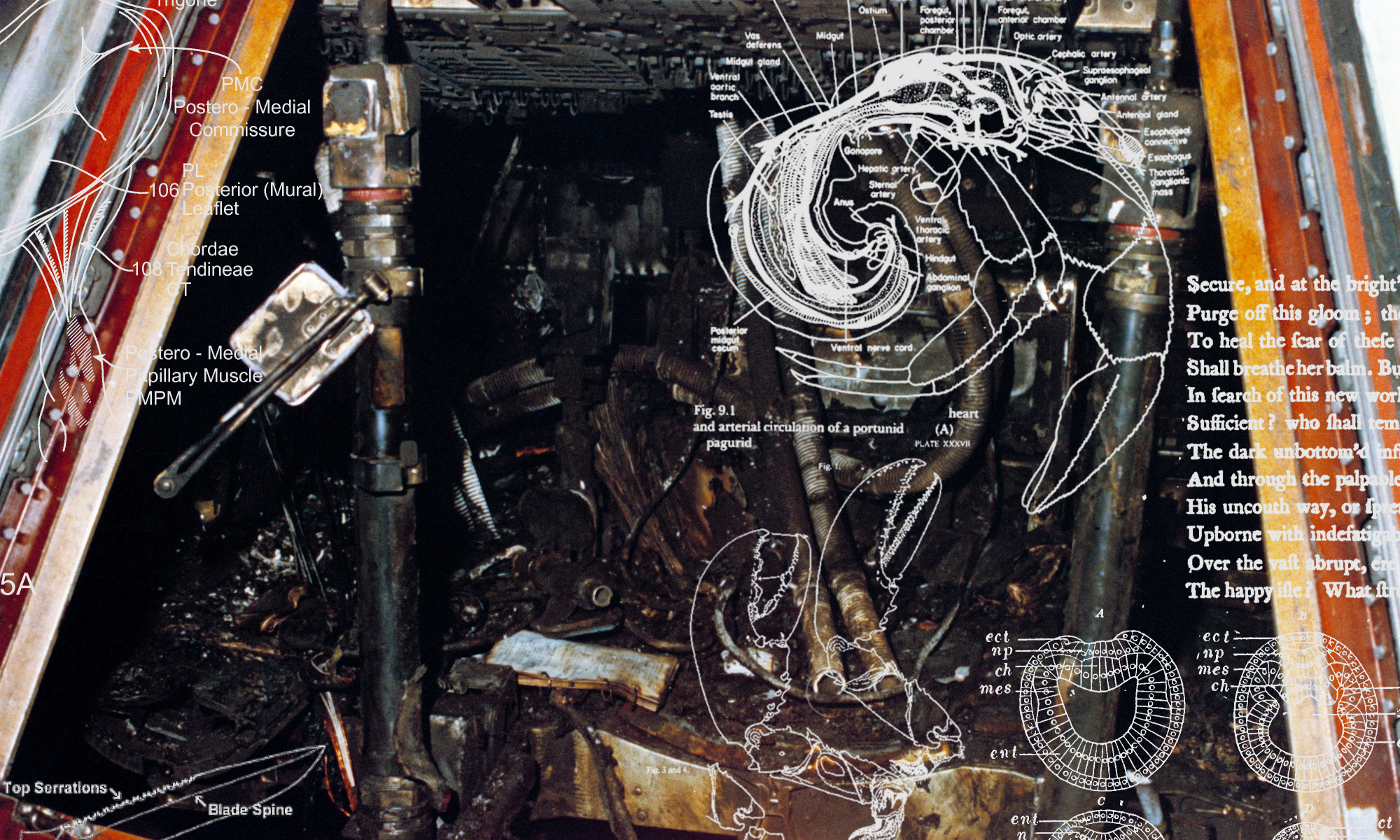

Just as fizzing water seeps from the earth, the chthonic and chaomantic black sun (sol niger) of the Pepsi Alph dwells within the ‘mantle’ of Creation, waiting to extravasate and haemorrhage the world with sugary, hydraulic nigredo. As total primordiality, it dwells deep within all existences: even, as we have seen, God himself. As Jung writes, “[t]artar settles on the bottom of the vessel, which in the language of the alchemists means: in the underworld, Tartarus”.[note]Carl Gustav Jung, The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, (Princeton University Press, 1981), 301.[/note] And certainly, we can trace the genetic history of Pepsi even further back into greater entanglement with Paradise Lost via the deep link between carbonation and the infernal abysm of Hell. That is, in one final synchronicity, we shall document how Pepsi’s genetic history can be traced all the way back to Hell itself (in its actual, real world instantiation).

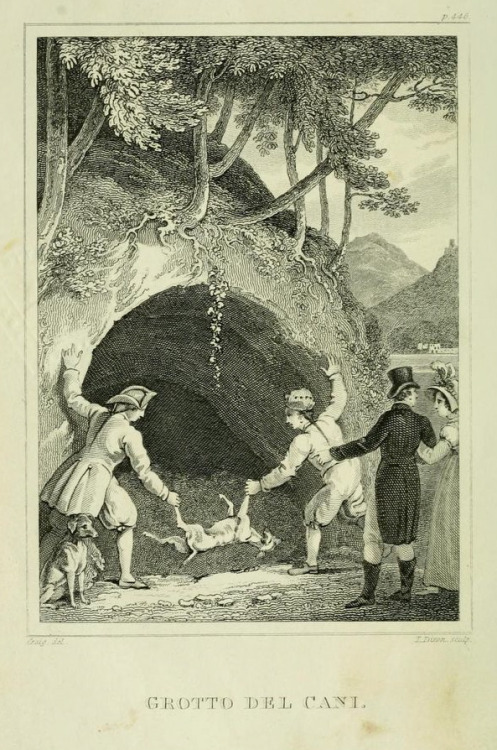

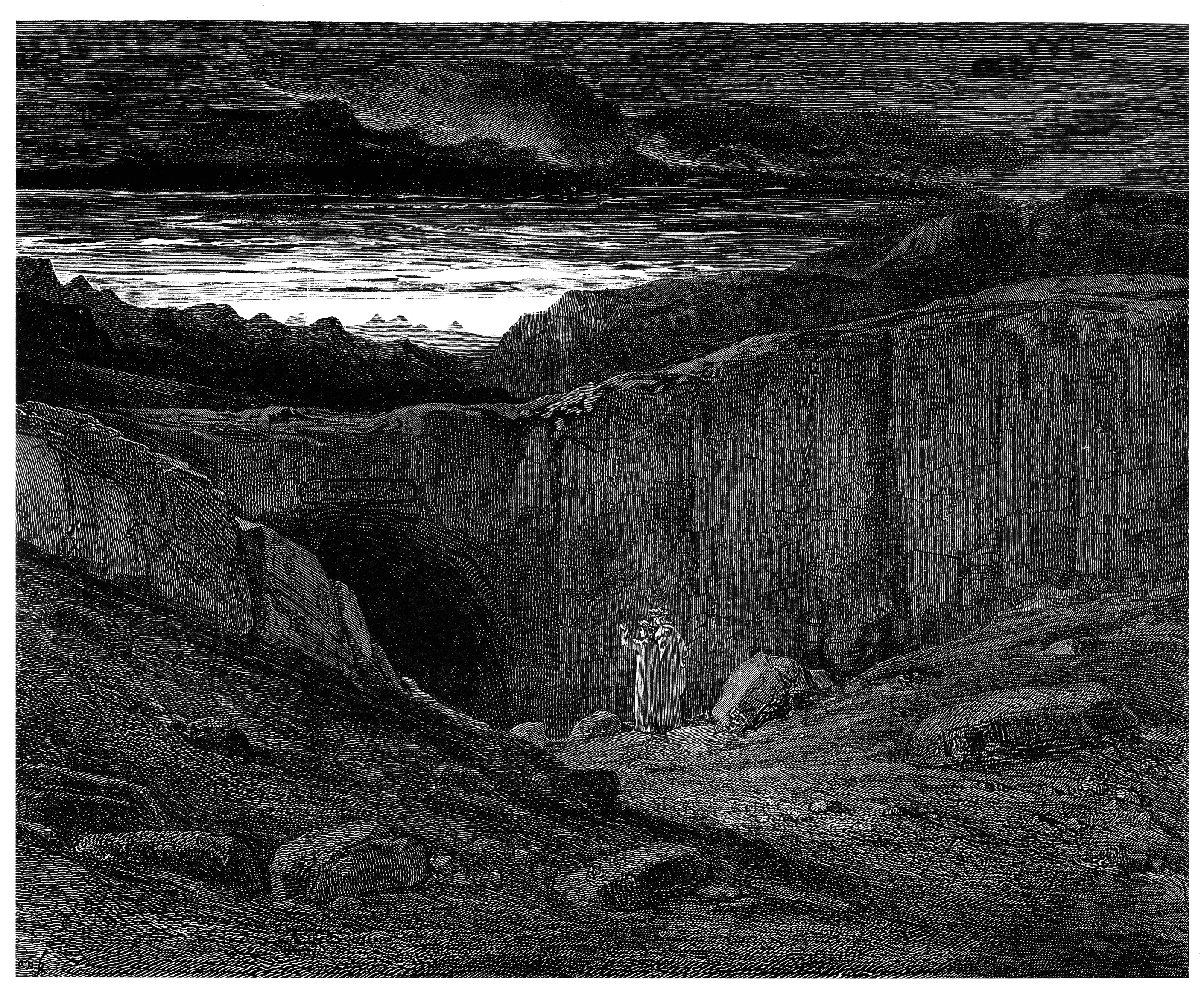

Van Helmont had noticed that ‘gas sylvestre’ was liable not only to collect within breweries and wine cellars but also within certain caves. In this, he was most likely referring to the infamous Cave of Dogs (‘Grotto del Cani’) near Naples. Athanasius Kircher had previously documented the effect of an unknown gas (CO2) in the cave. Pooling at the bottom, it would cause dogs to asphyxiate (whence the cave draws its name), whereas their human counterparts (with orthograde posture safely positioning their mouths above the layer of pooled CO2) would survive. This phenomenon had been documented since the ancients, and was suitably well-known. Furthermore, it was van Helmont who identified this canine-killing substance as ‘gas sylvestre’ via his discovery of CO2. Of occult import is the fact that the very same noxious carbon dioxide that collects in the Cave of Dogs was also famed for emanating — in large quantities — from the neighbouring lake, the Lago d’Averno (‘Lake Avernus’). Both are located within the Solfatara region (which gains its name from the Italian word for ‘sulphur’), itself part of the Phlegraean Fields (i.e. ‘burning fields’), famous throughout Italian literature for being the geographical location of the entrance to Hell. Both Dante and Virgil locate Hell’s entrance within the fuming Lake Avernus; and the Romans, similarly, thought it to be within the craters of the Solfatara. Crucially, the entire reason for choosing this area for the geolocation of Hell’s gate was entirely down to the area’s noxious carbon emissions. The Solfatara’s carbonic gas fumes feature prominently in the literature, with Virgil famously alluding to the idea that birds could not fly over the area without suffocating.[note]Cf. Salomon Kroonenberg, Why Hell Stinks of Sulfur: Mythology and the Geology of the Underworld (Reaktion Books, 2013).[/note] In suitable fashion, a naturally carbonated spring named ‘Pisciarelli’ was located nearby — the source of medicinal fizzy water long thought to cure chronic diarrhoea. (Since balneology really takes off in Ancient Rome, these springs would have been amongst the first used for their restorative properties: thus, it would have certainly been one the places where the ancient collocation of fizz and digestion was birthed.)

The history of carbon dioxide — and thus Pepsi — begins in the entrance to Tartarus: curiosity concerning the emanations in this hellish cave is what originally alerted thinkers to the properties of carbonic gas. We thus see how this ancient Roman entrance to Hell’s domain originally inspired the study of carbonation by alerting early modern savants to the presence of gases separate from air, which — in turn — led to van Helmont’s discovery of carbon dioxide… and the rest, as we know, is history. Thus, finally, we see how fear amongst the Ancients of Hell’s lethal fumarole emissions transformed, over the long centuries, into the 19th-century invention of Pepsi Cola. Bubbling down through Virgil, Dante, Kircher, Paracelsus, van Helmont, Priestley, Schweppe, and Bradham, the toxic carbon fumes of Tartarus were eventually converted into the carbonated tartar we line our guts with daily, on a global scale.

BRAD’S DRINK = 190 = TARTARUS

Pepsi, quite simply, was forged in Hell.[note]And, like Hell (as the spatialisation of revolt), Pepsi marks the tendency for dark materials to switch into self-selection, outstripping the centralised planning that originally created them.[/note] Appropriately, Hell is — in the Kabbalistic tradition[note]PEPSI = 110 = KABBALAH [/note] — also referred to as ‘Tehom’ (meaning ‘the depths’), which, in turn, also refers to the surging liquid ‘Deep’ or ‘Abyss’ prior to Genesis’s creation: a carbonic black Tehom[note]PEPSI ABYSM = 215 = TIME TRAVEL [/note] — as prima materia — is the tartareous Deep, effervescing beneath and within creation. (Notably, ‘Tehom’ is also cognate with ‘Tiamat’.[note]”Before the gods there was only Tiamat, the bitter water, her companion Apsu, the sweet water, who is also Abzu (the abyss), and “that return to the womb” — or matrix-implex — her Mummu.” Cf. https://web.archive.org/web/20170622210905/http://www.ccru.net/archive/splitsecond.htm[/note]) Indeed, in the physico-theological understanding of the 17th century, this ‘Tehom’ (or Hypogene Abyss of Chaos) was believed to still reside deep within the Earth’s crust: and the existence of this tellurian chaos ocean was employed, accordingly, as the causal explanation for the Noachic Flood. Thomas Burnet documented how this indwelling, chthonic ‘Tehom’ (as tellurian chaos ocean) had broken forth, from the “fountains of the deep”: literally causing the world to fizz with abyssal liquid. We note that “fountain” originally comes from “font”: denoting any fizzy mineral water spring (from which we get the term ‘soda fountain’). And, as we have seen, people have, since the Ancients, considered the depths of Hell to be the source of plutonic carbonation and infernal fizz. Certainly, Burnet’s description of this “Tehom Rabbah” (‘Great Deep’)[note]TEHOM RABBAH = 192 = UTTUNUL [/note] enforces this. The contemporary understanding of diluvial geology proposed that the planet literally effervesced at the Flood: that it was broken down into constituent elements, in a mix of Air and Water (with Solids sinking to the bottom). Pepsi surged from the depths, as templex prima materia. And, as Paradise Lost details, it could well happen again.

Troublingly, however, Paradise Lost — as we have been proposing in this essay — also allows for this relapse to occur outside of divine decree. Because of Milton’s materialist voluntarism, synecdochal revolt — ontological dyspepsia — is always possible: indeed, this is exactly how Satan’s coup was able to happen. A part loops back into itself, and begins to simulate or feign autonomy. As Milton implies, all terrestrial nature could collapse. He writes that, had the war in heaven ensued,

nor only Paradise,

In this commotion, but the starry cope

Of heaven perhaps, or all the elements

At least had gone to wreck, disturbed and torn [PL; iv.991-4]

It is the clean hyaline — “the starry cope / Of heaven” — whose task, as a cosmic integument, is to immunise the cosmos against the “loud misrule of Chaos”, lest “extremes / Contiguous might distemper the whole frame” [PL; vii.271-4]. Yet, despite this, had “not soon / the Eternal” repressed this ontic rebellion, the hyaline would have denatured and the whole of nature lapsed into auto-immunity, returning to dyspepsia and chaos [PL; iv.992-3]. Walter Charelton had written of the need for “continuall renovation and reparation” of all creaturely existences, for fear that “the whole Fabrick” be destroyed by chaotic “decayes”.[note]Walter Charleton, Natural History of Nutrition, Life, and Voluntary Motion, Containing all the New Discoveries of Anatomist’s and Most Probable Opinions of Physicians, concerning the Oeconomie of Human Nature: Methodically Delivered in Exercitations Physico-Anatomical, (London, 1659), 91.[/note] In Milton’s Comus, the eponymous character delineates the basal superfluity of nature, explicating the possibility of an overly creative abortion in her universal womb:

[She] would be quite surcharged with her own weight,

And strangled with her waste fertility;

The earth cumbered, and winged air darked with plumes,

The herds would over-multitude their lords,

The sea o’erfraught would swell, and the unsought diamonds

Would so emblaze the forehead of the deep [ll.727-32]

Insubordinate ontological excess. Meltdown. Base matter rebellion. Internal insurrection. We note the use of the language of overflowing and overabundance: of a plenitude gone rotten. Increatum is, again, “the womb of nature and perhaps her grave” [PL; ii.911]. Nature as basilisk. By “unsought diamonds”, perhaps, Milton was imagining the tartrate crystals that are produced as superfluities of fermentation.

In this light, Satan — again — is revealed as merely a symptom or vector of Chaos’s liquefaction of reality (a vector later taken up, after being passed on by Satan to Capital, by the chemical known as Pepsi-Cola). Satan is a conduit for producing localised fonts of Tehom relapse. He expedites the return of the tartar that lies as potential within all materials. Pandæmonium is a perfect example: Satan opens a “spacious wound” in the hill, “scumm[ing] the bullion dross” causing “a fabric huge” to rise “like an exhalation” (a flatulence) out of the earth [PL; i.689, 710, 704, 711]. His demonic “crew” recapitulate the original excrementation of Creation’s “infernal dregs”, dragging pandemonium into the world, and bringing yet more excess into Creation. (Unsurprisingly, the diabolical architecture is described as arising from a “womb” — of “metallic ore” and “sulfur” [PL; i.673-4].) Even more striking is Satan’s provocation of the very Empyrean to belch weaponised chaos out of the ground in the form of the Satanic war-machines. Before pulling his cannons out of the ground, the Prince of Pandæmonium describes his very own “dark materials” before the act:

Which of us who beholds the bright surface

Of this etherous mould whereon we stand,

This continent of spacious heav’n, adorned,

With plant, fruit, flower ambrosial, gems and gold,

Whose eye so superficially surveys

These things, as not to mind from whence they grow

Deep underground, materials dark and crud,

Of spirituous and fiery spume, […]

These in their dark nativity the deep

Shall yield to us, pregnant with infernal flame [PL; vi.472-85]

Here, the very spinal cord of the verse encrypts the return to chaotic depths: both logically and on the page itself, a descensus ad inferos — a katabasis into the womb of chaos — is presented. The abyssal and dyspeptic chaos, in its “dark nativity”, is the unruly ground of all that walks the “bright surface” which the “eye so superficially surveys”. The surface is easily peeled away and discarded: the depth “yields to us” chaotic forms abundant. It is further stressed that these materials are even “as not to mind” in order to emphasise their ability to escape, to flood around, mental structures and intelligibility. This matter isn’t just ontologically distal from thought, it is against conceptual thought. Satan is an artist of Chaos, but also therefore only its agent and its puppet. He draws the fizziness of Pepsi-Tehom to the surface. Indeed, van Helmont himself had written that the alchemist can draw “a wild and pernicious Gas [aka Chaos] out of coals, Stygian waters and fusions of minerals”.[note]Georgiana D. Hedesam, An Alchemical Quest for Universal Knowledge: The ‘Christian Philosophy’ of Jan Baptist van Helmont (1567-1644), (Routledge), 133.[/note] In his act of infernal chemical ingenuity, Satan’s yielding of weaponised Chaos is related to daemonic invention (like that of the poet):

The invention all admired, and each, how he

The inventor missed, so easy it seemed once found,

Which yet unfound most would have thought

Impossible. [PL; vi.498-500]

Invention (poetic, industrial, technocommerical, chaomantic) straightforwardly just is the paradox of auto-production: because of its inherently circular causality, it only makes sense retrospectively and is never predictable prospectively. Simultaneously anastrophe and catastrophe, it drags previous impossibilities into being. Tearing the consistency of reality as it smears the real across itself. This hellish alchemical “invention” results in Satan’s “devilish machinations” [PL; vi.504], when (upon the “[c]oncot[ion]” of “[t]he originals of nature”) the entrails of the heavens belch forth (like “thundring Ætna”) demonic anal cannons:

in a moment up they turned

Wide the celestial soil, and saw beneath

The originals of nature in their crude

Conception; sulphurous and nitrous foam

They found, they mingled, and with subtle art,

Concoted and adjusted they reduced

To blackest grain, and into store convey:

Part hidden veins digged up (nor hath this earth

Entrails unlike) of mineral and stone, [PL; vi.509-17]

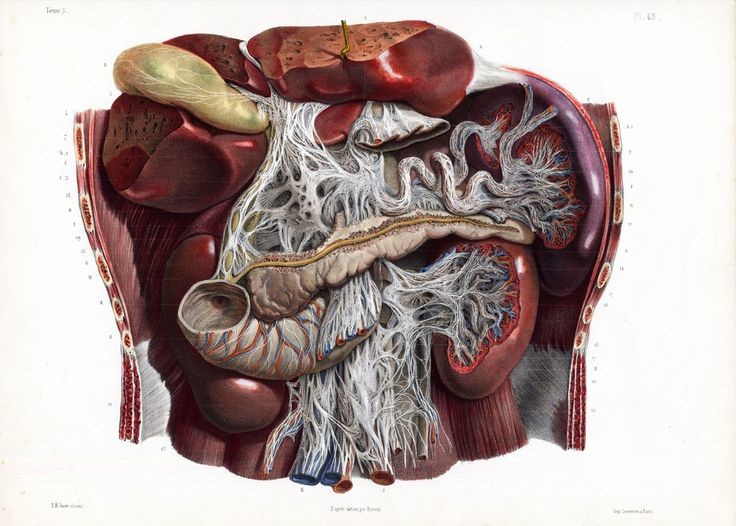

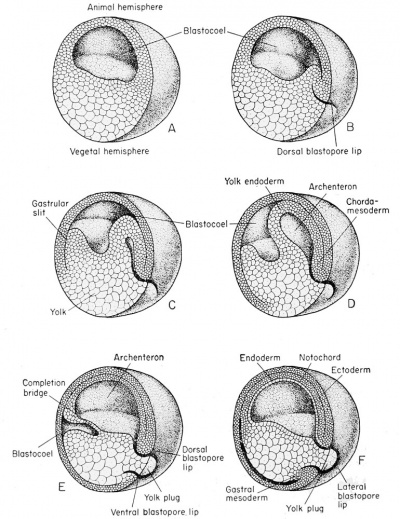

Paracelsians often imagined hypogene actions (the actions of mineral and stone) as the production of a geocosmic archeus. Duchesne, for example, envisioned metals concocted by “heate, by force wherefore mettales congealed in the bowels of the earth are diposed [and] digested”.[note]A.G. Debus, The French Paracelsians: The Chemical Challenge to Medical and Scientific Tradition in Early Modern France, (Cambridge University Press, 1991), 34.[/note] Satan is reactivating the shit, the dyspepsia, of the geontic coelom. His infernal artillery is the regurgitation and recrudescence of God’s uncontrollable, fallopian, pepsoidal chaos. Pulling up these dark materials, he harnesses the excessiveness of matter that God had to excrete, utilising its attendant autonomy from divine forms, therefore turning “waste fertility” to “devilish machinations”. He increases the resistance of this materia to incorporation back into the homeostatic divine-archeus-system. This is the job that Satan fulfils throughout the poem: a force of cosmic deregulation, he creates problems for digestive bureaucracy / God-as-culinary-homeostat. A vector of Chaomantic Libertarianism, Satan is the peptic ulcer in the archeus of Milton’s universe.

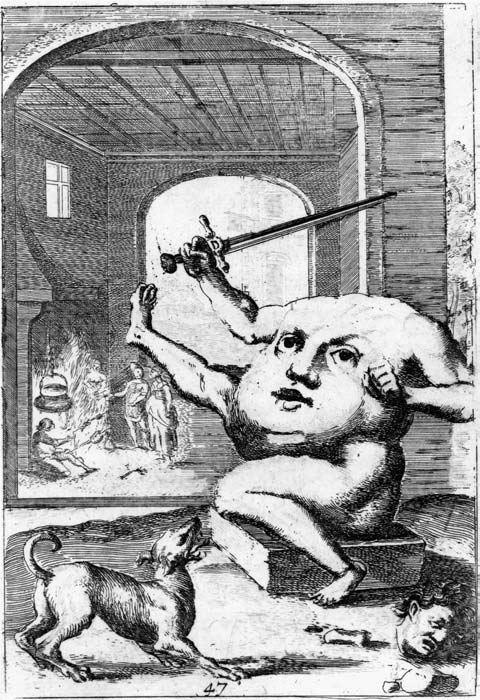

In Comus, Milton had envisioned a similar motif of chaotic voluntarist revolution. As previously quoted, Milton describes — in a curious acephalic image — an overripe geocosm auto-producing a superfluous accretion of “unsought” diamonds that proceed to “emblaze the forehead of the deep” [ll.731-2]. Milton goes on to describe these chthonic, chaomantic stars becoming “so bestud” with subsidiary glimmer

that they below

Would grow inured to light, and come at last

To gaze upon the sun with shameless brows [ll.743-5]

The coccyx of the cosmos erupts through the cranium. Indeed, this is the perfect exemplar of synecdochal revolt. Here, the self-fed “waste fertility” of a subterraneous pseudo-star comes to overflow its role as a ‘Part’ and thus, in runaway auto-intensification, comes directly to compete with the ‘Whole’: this sol niger — as malignant telluric beam — comes to “gaze upon the [original] sun with shameless brows”. Through its crushing superfluity, the blinding darkness of this Pepsi-Sun — like Milton’s own blindness — blots out the true, and primary, lightsource of the world. The idea of Tehom, “the deep”, overthrowing true luminosity with its own excessive “darkness visible” finds parallels with Milton’s own delineation of aggressive blindness. The process of Satanic revolt (in which the Part comes to “gaze upon” the Whole) is not unnatural, quite the opposite: it the natural state of all matter. It is Means-Ends subversion. Fed on itself and looped back into its own dyspeptic pregnancy, hylomorphism becomes rotten, cancerous, and apoptotic. Moreover, it is the revocation of all top-down rule: the insuperable capacity for internal revolt and usurpation, unbeholden to any organisation, be it cosmic, organic, intellectual or political. As a form of solar self-decapitation from below, it resembles the image of the ‘belly revolting against the head’, which, in Milton’s time, had become a prime metaphor for the regicide and revolution. This is to be expected, what with the dissolution of Parliament being referred to as the ‘Purge’ and the replacement skeleton-Parliament dubbed the ‘Rump’. The Body Politic had become autoacephalic: God and King, as the head, had been decapitated by the rest of the body (quite literally in King Charles’ beheading) — the rebellious parliament or the deregulatory tartar of God’s own scatological ex deo creation. This autoacephalica and self-cannibalisation was perfectly captured in numerous contemporary illustrations and reimaginings of Aesop’s autoanthropophagic “Fable of the Belly and the Members”:

Here we witness the fear of auto-production encapsulated. It is a role now fulfilled by capital rather than any human political agitation: for, by operating primarily as a form of metynomic usurpation (whereby mere means swell, through self-selection, into ends-in-themselves), it comes to be symbolised by Pepsi (as avatar for the superstimuli revolt of the belly against the head, or desire against norms). Pepsi retrojects itself as the true subject of history: glucose hunger replaces human goals. And so, we come to full appreciation of the templex connection between Pepsi and Chaos: Miltonic Chaos is about Pepsi because Miltonic Chaos becomes real as Pepsi. As Pepsi tends towards producing itself, and only itself, the entire universe is beholden to terminal Dyspepsia, and we envision Burnet’s account of the flood returning once more. The Earth will burst forth with the black tartar of nigredo: Tehom and Tiamat return ascendant. Creation is not becoming more crystalline, but more faecal and tartareous. What, then, is the end-point of this effervescing of existence, this ontological skotison? As one of the brothers explains in Comus:

But evil on itself shall back recoil,

And mix no more with goodness, when at last

Gathered like scum, and settled to itself

It shall be in eternal restless change

Self-fed, and self-consum’d, if this fail,

The pillared firmament is rottenness

And earth’s base built on stubble. [ll.592-8]

If this is not a statement of demonic rebellion as cybernetic positive feedback, then it is hard to say quite what else it could be. Circling into itself, as evil “on itself shall back recoil”, it becomes auto-productive, “[s]elf-fed and self-consum’d”. This is Milton’s model of cybernetic take-off. Here, he truly was acting as the blind prophet of Capital’s tendency towards metonymic (demonic) revolt: Human production tends towards replacement with Pepsi production. Increasingly, we live to consume rather than consume to live. And, with stunning prophetic acuity, Milton sees that the result of all this is meltdown: return to nigredo, tartar relapse, sol niger implosion… The great Pepsi fountains of the Earth break forth, “pillared firmament is rottenness” and “earth’s base built on stubble”.

Pepsi invents itself from the future. ![]()

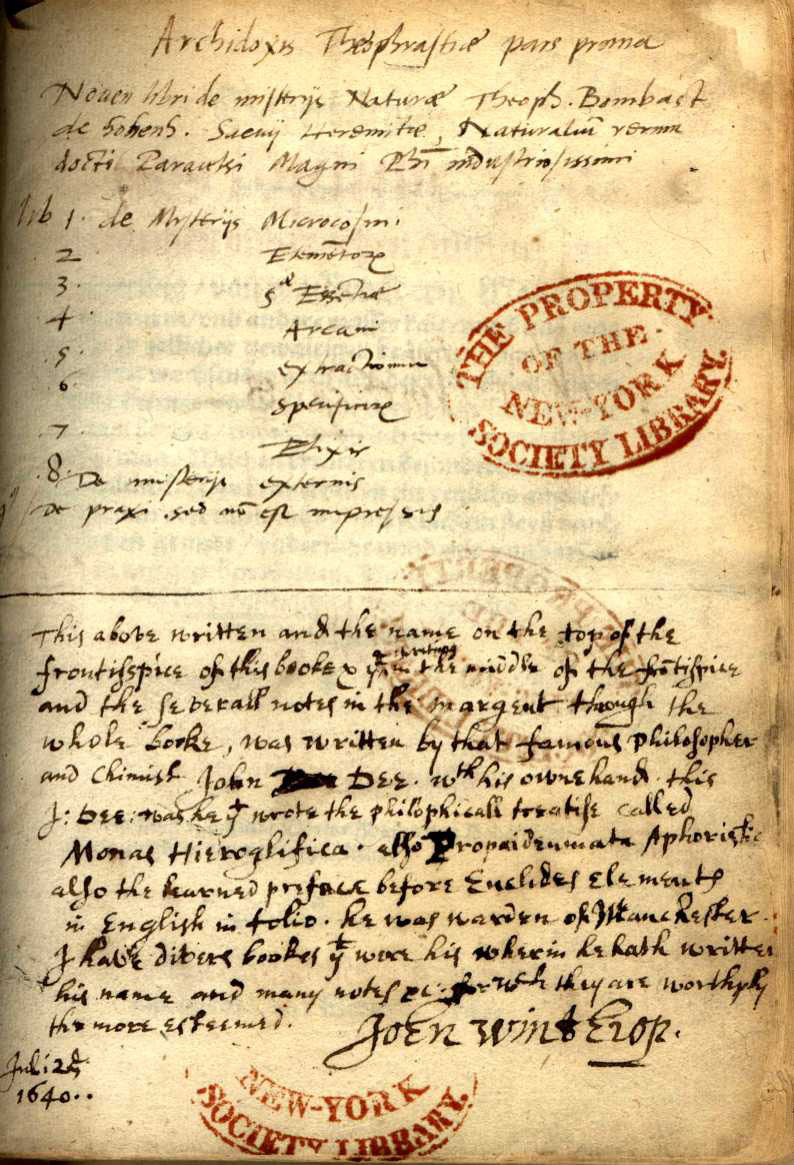

[/note] Always obsessed with digestion, Paracelsus was quick to focus discussion upon the supposedly eupeptic properties of the water. He praised carbonated spring water as “driv[ing] away gout, and mak[ing] the stomach as strong in digestion as that of a bird that digests tartar and iron”.[note]Walter Pagel, Paracelsus: An Introduction to Philosophical Medicine in the Era of the Renaissance (Karger, 1982), 26.[/note] Imagining the ‘occult’ powers of the earth’s chthonic healing laboratories — fizzing forth at the surface in this natural medicine — Paracelsus became enthused: he attempted to artificially recreate the fizziness, but met with no success. It was, as we have seen, only with his apprentice, van Helmont, that this effervescence first became the subject of reverse engineering, thus opening the pathway to the industrial and globalised production of soft drinks. Speculating even that the acidity of the spa waters held some occult connection with gastric acid, Paracelsus and van Helmont enthusiastically opined that carbonated waters were better than almost any other medicines. Bolstering an enduring fascination with the fizziness that seeps from the planet’s chthonic depths — stretching back to Hippocrates, and becoming more popular throughout the Middle Ages — the iatrochemical tradition helped to fully entrench the connection between fizz and eupepsia in the public consciousness.

[/note] Always obsessed with digestion, Paracelsus was quick to focus discussion upon the supposedly eupeptic properties of the water. He praised carbonated spring water as “driv[ing] away gout, and mak[ing] the stomach as strong in digestion as that of a bird that digests tartar and iron”.[note]Walter Pagel, Paracelsus: An Introduction to Philosophical Medicine in the Era of the Renaissance (Karger, 1982), 26.[/note] Imagining the ‘occult’ powers of the earth’s chthonic healing laboratories — fizzing forth at the surface in this natural medicine — Paracelsus became enthused: he attempted to artificially recreate the fizziness, but met with no success. It was, as we have seen, only with his apprentice, van Helmont, that this effervescence first became the subject of reverse engineering, thus opening the pathway to the industrial and globalised production of soft drinks. Speculating even that the acidity of the spa waters held some occult connection with gastric acid, Paracelsus and van Helmont enthusiastically opined that carbonated waters were better than almost any other medicines. Bolstering an enduring fascination with the fizziness that seeps from the planet’s chthonic depths — stretching back to Hippocrates, and becoming more popular throughout the Middle Ages — the iatrochemical tradition helped to fully entrench the connection between fizz and eupepsia in the public consciousness.

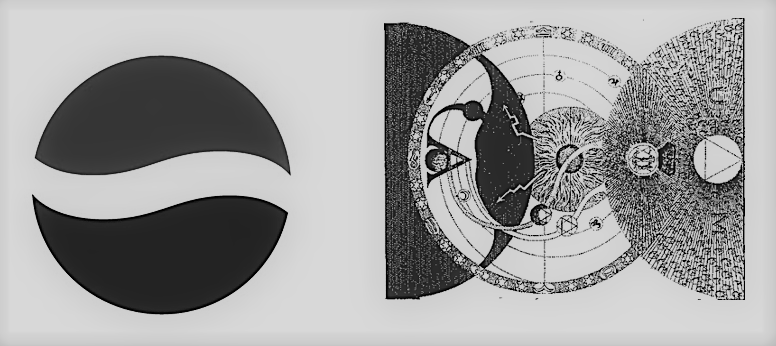

[/note] Milton describes how God “as with a mantle did invest / The rising world of water dark and deep, / Won from the void and formless infinite”: he provides it with a protective skin, a form-suffusing “mantle”. As such, through wrapping the entire created universe in a “clear” liquid sack, this “crystalline ocean” becomes purposed with protecting the cosmos from the “loud misrule” of the Chaos that lies just beyond it [PL; vii.269, vii.271].[note]Chaos is, thus, analogical to the ‘energetic excess’ that Freud describes as facilitating the epithelial individuation of the originary vesicle, in his account of metapsychological abiogenesis, in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (Penguin, 2003).[/note] It is therefore a prophylaxis against an external chaoticism, and — as such — a spheroid cosmic immune system and metaphysical life support.[note]Cf. Peter Sloterdijk, Globes: Macrospherology, Volume II: Spheres (Semiotexte, 2014).[/note] A crystallic womb. Certainly, pre-Copernican cosmology is precisely a cosmology of ‘immuno-containment’, and containment takes place across similar mediums (containment implies infinite divisibility); thus, to stress the ‘containment’ of the sublunary within the “hyaline”, as Milton does, is to impart some of the latter’s “crystalline” perfection to our own world. In other words, through its vitreous dialysis, this primum mobile acts as a vesicle purposed with separating Creation from Chaos: the happy harmony of this amniotic encasement — a placental harmony, therefore, between sublunary fundament and crystalline firmament and achieved through the shared medium of crystal perspicuity — announces the pre-lapsarian stability of Paradise Lost’s “new-made world”. Nonetheless: just as there was something wrong at the heart of the Crystal Pepsi venture, predestining it to fall, so too is there a blackening necrosis within this pellucid womb of Milton’s fictional cosmos.

[/note] Milton describes how God “as with a mantle did invest / The rising world of water dark and deep, / Won from the void and formless infinite”: he provides it with a protective skin, a form-suffusing “mantle”. As such, through wrapping the entire created universe in a “clear” liquid sack, this “crystalline ocean” becomes purposed with protecting the cosmos from the “loud misrule” of the Chaos that lies just beyond it [PL; vii.269, vii.271].[note]Chaos is, thus, analogical to the ‘energetic excess’ that Freud describes as facilitating the epithelial individuation of the originary vesicle, in his account of metapsychological abiogenesis, in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (Penguin, 2003).[/note] It is therefore a prophylaxis against an external chaoticism, and — as such — a spheroid cosmic immune system and metaphysical life support.[note]Cf. Peter Sloterdijk, Globes: Macrospherology, Volume II: Spheres (Semiotexte, 2014).[/note] A crystallic womb. Certainly, pre-Copernican cosmology is precisely a cosmology of ‘immuno-containment’, and containment takes place across similar mediums (containment implies infinite divisibility); thus, to stress the ‘containment’ of the sublunary within the “hyaline”, as Milton does, is to impart some of the latter’s “crystalline” perfection to our own world. In other words, through its vitreous dialysis, this primum mobile acts as a vesicle purposed with separating Creation from Chaos: the happy harmony of this amniotic encasement — a placental harmony, therefore, between sublunary fundament and crystalline firmament and achieved through the shared medium of crystal perspicuity — announces the pre-lapsarian stability of Paradise Lost’s “new-made world”. Nonetheless: just as there was something wrong at the heart of the Crystal Pepsi venture, predestining it to fall, so too is there a blackening necrosis within this pellucid womb of Milton’s fictional cosmos.

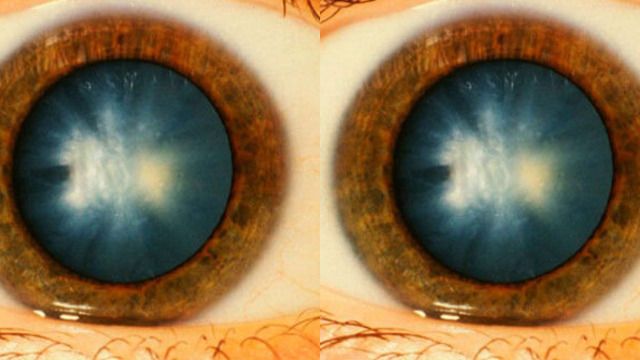

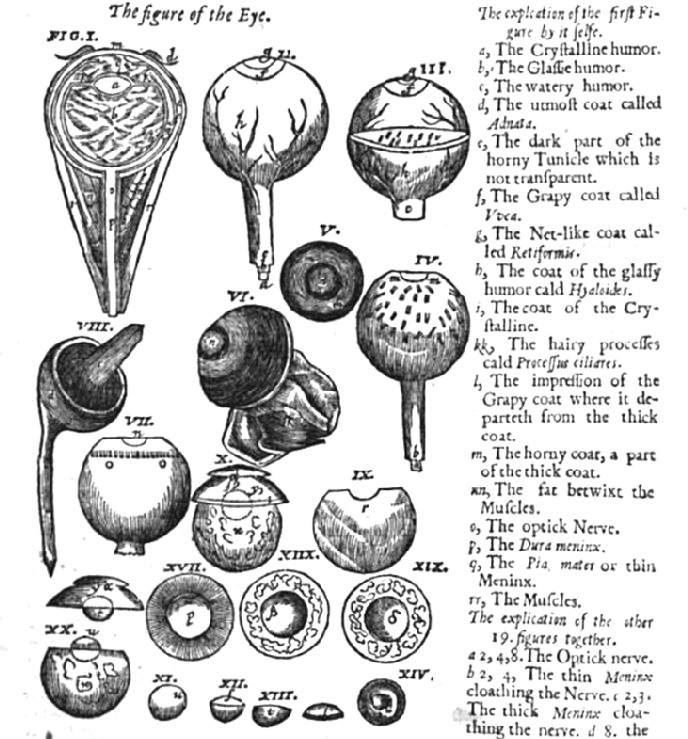

[/note]). Just as the planets are ‘contained’ within the life-support of the supernal realm, so too are our bodies, vouchsafed via the microcosm-macrocosm concordance of eyeball and firmament. ‘[T]here is a double firmament, one in the heavens and one in each body, and these are linked by mutual concordance’[note]Walter Pagel, Joan Baptista Van Helmont: Reformer of Science and Medicine (CUP, 2002), 99.[/note] This semantic entanglement between eyeball-strcuture and cosmos-structure is, unsurprisingly, ancient. As the Talmud, which Milton was familiar with, puts it:

[/note]). Just as the planets are ‘contained’ within the life-support of the supernal realm, so too are our bodies, vouchsafed via the microcosm-macrocosm concordance of eyeball and firmament. ‘[T]here is a double firmament, one in the heavens and one in each body, and these are linked by mutual concordance’[note]Walter Pagel, Joan Baptista Van Helmont: Reformer of Science and Medicine (CUP, 2002), 99.[/note] This semantic entanglement between eyeball-strcuture and cosmos-structure is, unsurprisingly, ancient. As the Talmud, which Milton was familiar with, puts it: