by Xenogoth

0

Such a lot the gods gave to me — to me, the dazed, the disappointed; the barren, the broken. And yet I am strangely content, and cling desperately to those sere memories, when my mind momentarily threatens to reach beyond to the other.[note]H.P. Lovecraft. “The Outsider” in The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories. (London: Penguin Classics, 2002), 43.[/note]

H.P. Lovecraft’s short story The Outsider first appeared in the April 1926 issue of pulp fiction magazine Weird Tales. It certainly suits such a publication. A surreal story full of inconsistencies and implausibilities, theories abound as to the scenario it is actually describing.

S.T. Joshi, writing explanatory notes for the story in a Penguin Classics collection of Lovecraft’s tales, wonders if the story is an account of a dream or if the unnamed protagonist is a ghost or immortal being, doomed to haunt the shadowy castle in which they find themselves, with so much time having past that the outsider no longer remembers how they came to be.[note]S.T. Joshi, “Explanatory Notes: ‘The Outsider’” in Ibid., 373.[/note]

There is no final resolution to this endlessly interpretable story. What carries the narrative is not the horror of the unknown outside the castle, but the horror of the outsider’s own interiority; their imprisoned subjectivity — there are no mirrors with which they can see their appearance and they have no recollection of hearing another human voice, “not even my own; for although I had read of speech, I had never thought to try to speak aloud”.[note]H.P. Lovecraft. “The Outsider”, 44.[/note]

Whilst apparently more at home amongst the skeletal dead than the painted portraits of the ‘living’ that line the castle’s walls, and having little memory of how they came to arrive in their present circumstances, the Outsider is driven by a curiosity to discover the world outside the castle they habitually call home.

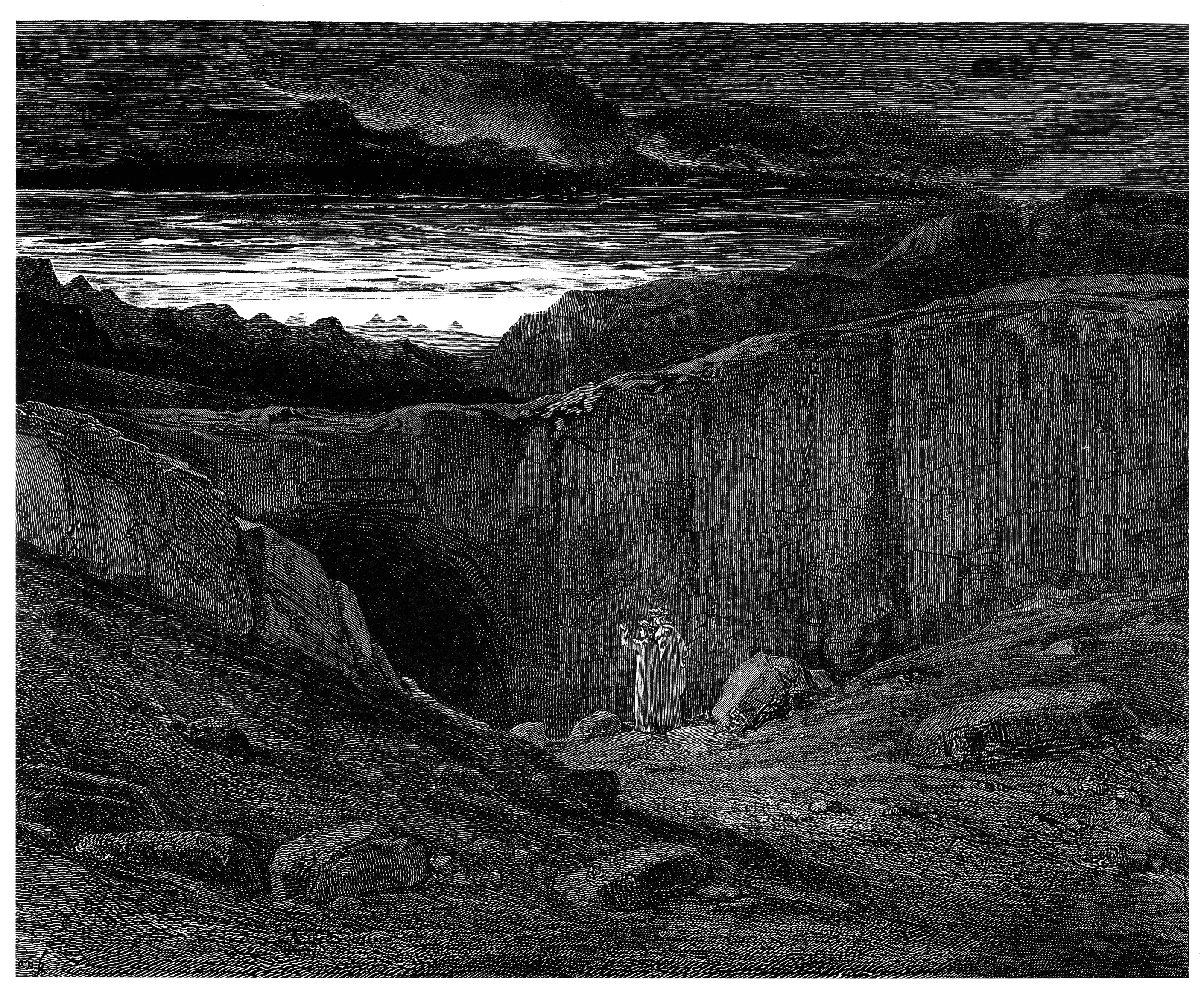

The journey to the Outside is fragmentary and dream-like. Stumbling bewilderedly through non-Euclidean environs trying to glimpse the night sky, the Outsider eventually comes across a party in a castle that looks unnervingly like their own, albeit ruinous in other parts than the one they are familiar with. They enter only for all in attendance to flee in terror.

Seeing the horror from which the revellers have fled — something “not of this world — or no longer of this world — […] a leering, abhorrent travesty of the human shape”[note]Ibid., 48.[/note] — the Outsider soon realises that this terrifying face belongs to them, at first unable to reconcile the interior Self with the gruesome image of the Other reflected in “a cold and unyielding surface of polished glass”.[note]Ibid., 49.[/note]

With this revelation, that the Outsider is the Other and always was, the story ends…

1

Lovecraft’s weird tale speaks specifically to a passage found in the introduction to Mark Fisher’s 2016 book The Weird and The Eerie — a passage which echoes persistently throughout the rest of the text, signalling to Fisher’s best-known writings on the psychosocial affects of capitalism.

Considering capital as the ultimate “eerie entity”, Fisher wonders about the ways

that “we” “ourselves” are caught up in the rhythms, pulsions and patternings of non-human forces. There is no inside except as a folding of the outside; the mirror cracks, I am an other, and I always was.[note]Mark Fisher, The Weird and the Eerie (London: Repeater Books, 2016), 11-12.[/note]

Following this, it is fitting that Fisher then begins his book with an exploration of the works of H.P. Lovecraft. He notes that “it is not horror but fascination — albeit a fascination usually mixed with a certain trepidation — that is integral to Lovecraft’s rendition of the weird”.[note]Ibid., 17.[/note] For Fisher, on both an aesthetic and political level, it is the weird that is desirable for its ability to “de-naturalise all worlds, by exposing their instability, their openness to the outside”.[note]Ibid., 29.[/note]

This contrasts, for example, with the eerie ghost stories of M.R. James, explored later in the book, for whom “the outside is always coded as hostile and demonic”.[note]Ibid., 81.[/note] Fisher continues: “the glimpses of exteriority [James’ stories] offered no doubt brought a thrill to his listeners, but they also came with a firm warning: venture outside this cloistered world at your peril”.[note]Ibid.[/note]

The Outside is a concept that has long haunted the history of philosophy under various different names and formulations — from the Kantian noumenon to the Lacanian Real, et al. — with each functioning as a challenge to subjectivity that attempts to think beyond phenomenal limit-experiences. Whilst this broad definition is applicable to the narratives in much weird fiction, these tales explore the Outside through narrated ‘experience’ rather than objective academic analysis and they do so with an imaginative flare that has fascinated many.

Eugene Thacker, for instance, in his book In The Dust of Our Planet, explains that rather than write a “philosophy of horror” he hopes to articulate “the horror of philosophy: the isolation of those moments in which philosophy reveals its own limitations and constraints, moments in which thinking enigmatically confronts the horizon of its own possibility — the thought of the unthinkable that philosophy cannot pronounce but via a non-philosophical language”.[note]Eugene Thacker, In the Dust of Our Planet (London: Zero Books, 2011), 2.[/note]

Lovecraft’s The Outsider is an interesting example of such non-philosophical language as it is written from a seemingly impossible perspective. Its narrative viewpoint actively resists being imaginable to the reader. Imprisoned by their own subjectivity, the Outsider is shielded from the objective truth of their existence, but to see themselves — to witness the inside as a folding of the outside — is as intolerable as any encounter with pure exteriority. There is no moving beyond the weird tale’s final moment when the Outsider crosses the event horizon of their subjectivity and irreversibly lets the Outside in.

Whilst Lovecraft’s tale explores the horror of the Outside in the first-person (or, more accurately, non-person), most stories like it are told one step removed, exacerbating the intolerability of such a first-hand experience. Those who have experienced the horror of the Outside first-hand are often driven insane, unable to articulate their experience with any lucidity. A typical example of this can be found in Lovecraft’s best-known tale, The Call of Cthulhu, which is told through a first-hand reading of secondary accounts, including a police report written by Inspector John R. Legrasse who, notably, describes his encounter with a ‘Cthulhu Cult’ of Outside-worshippers.

The cult represent the Outside as a comprehensible and material social threat, far more visibly dangerous than the misadventures of the atomised individual in their collective channelling of the powers of the great Cthulhu. Whatever horrifying and unthinkable form the Outside may take, the fact remains that it is seemingly through community alone that its affects can be harnessed (whilst nonetheless remaining intolerable to the individual human mind).

Another example of this communal channelling can be found in Joan Lindsay’s 1967 novel Picnic at Hanging Rock, the focus of the last chapter of The Weird and the Eerie. Fisher writes that the novel “invokes an outside that certainly invokes awe and peril, but which also involves a passage beyond the petty repressions and mean confines of common experience into a heightened atmosphere of oneiric lucidity”.[note]Mark Fisher, The Weird and the Eerie, 122.[/note]

The novel begins with the disappearance of three students and one teacher from an all-girls’ boarding school in Victoria, Australia. The women, exploring a rock formation at the titular local beauty spot, go through a truly bizarre experience. Suddenly overcome by drowsiness, they fall asleep. One of the group, Edith — who is less susceptible to the lure of the Outside: “her inability to let go of [her] everyday attachments […] ultimately prevents her from making the crossing”[note]Ibid., 128.[/note] — awakens to find her peers in a trance, disappearing one by one behind the rocky monolith they had just been exploring, giving themselves over to an unknown agency.

The women are never seen again. The effect of their disappearance on the rest of their community is catastrophic. With no explanation for their absence, locals assume all kinds of violent ends for the women. The boarding school eventually shuts down as concerned parents withdraw their children and members of staff resign. The communal stress and grief reach their peak with two separate suicides: namely, a student, Sara, and the school’s headmistress, Mrs Appleyard. Whilst the missing women collectively embrace the Outside, the school community is traumatically undone by their exit.

The final sentences of Fisher’s book note how — unlike Edith — the women are

fully prepared to take the step into the unknown. They are possessed by the eerie calm that settles whenever familiar passions can be overcome. They have disappeared, and their disappearances will leave haunting gaps, eerie intimations of the outside.[note]Ibid.[/note]

Following Fisher’s suicide in January 2017, this ending is unsettling to read. Death is, of course, the ultimate limit-experience, the ultimate challenge to subjectivity, and here grief becomes the affective result of being haunted by the Outside through the absences that death imposes upon both individual and community.

Fisher’s death explicitly intensifies the stakes of his thought in this way, as his absence has become an eerie intimation of the very Outside that lurked in the background of all his writings. It must be remembered, however, that whilst death was a topic he discussed frequently, so was the collective subjectivity he saw as essential to any postcapitalist future.

Caring for one another with the intensity that so often follows grief renews the possibility of such a collective subject being established, a subject which “does not exist, yet the crisis, like all other global crises we’re now facing, demands that it be constructed”.[note]Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism (London: Zero Books, 2009), 66.[/note] Again, even in the very real instance of an individual’s death, it is through community that the affects of the Outside are channelled, whilst still remaining intolerable, and the political implications of this communal channelling are considerable.

Whilst such implications are not discussed in The Weird and the Eerie explicitly, in the context of Fisher’s wider writings the book reads like an aesthetic toolkit for ontopolitical ‘egress’ — that now-familiar new addition to the Fisher lexicon which he details, in his usual style, with pop-cultural instantiations rather than academic exposition. He writes:

Lovecraft’s stories are full of thresholds between worlds: often the egress will be a book (the dreaded Necronomicon), sometimes […] it is literally a portal. […] The centrality of doors, thresholds and portals means that the notion of the between is crucial to the weird.[note]Mark Fisher, The Weird and the Eerie, 28.[/note]

Fisher’s use of the word ‘egress’ is not expanded upon beyond this passage, yet it is striking in its unfamiliarity and remains in the imagination as a name given to a particular kind of paraontological experience. It is a word synonymous with ‘exit’ that was most commonly used in nautical and astronomical contexts in the 18th and 19th centuries — it is archaic whilst exemplifying a twinned relationship between oceanic depths and the vast cosmos, making it an appropriate term to invoke in the orbit of Lovecraft. Its etymological relationship to ‘transgress’ is suggestive also.

In his next book, Acid Communism, left in an unknown state of completion at the time of his death, Fisher was to address the political reality of egress more explicitly. He hoped to reinvigorate the psychedelic praxes of consciousness-raising/-razing that have come to culturally define the 1960s and ’70s, channelling them through his postcapitalist desires.

Similar approaches are already becoming visible within contemporary politics. For instance, the Conservative party in the UK continues to habitually ridicule and criticise the Jeremy Corbyn-led Labour party for wanting to drag the country back to the 1970s. Fisher would perhaps argue that what the Labour party are instead suggesting is the return of that decade’s rising class consciousness; a return to its potentials.[note]Fisher’s reappraisal of the 1970s is not unprecedented and he publicly cited John Medhurst’s That Option No Longer Exists: Britain 1974-76 (London: Zero Books, 2014) and Jefferson Cowie’s Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class (New York: The New Press, 2012) as major influences on his most recent thought — not to mention the philosophical texts by Deleuze & Guattari, Lyotard, Baudrillard, Marcuse, and Irigaray that emerged in that period following May ‘68.[/note]

In the unpublished introduction to Acid Communism, Fisher writes of this potential (if seemingly paradoxical) return of the new that capitalist realism[note]Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism (London: Zero Books, 2009). From Fisher’s book of the same name, capitalist realism can be very briefly summarised as the deeply held social belief — propagated by capitalism itself — that there is no realistic alternative to the capitalist system.[/note] repeatedly ungrounds:

In recent years, the sixties have come to seem at once like a deep past so exotic and distant that we cannot imagine living in it, and a moment more vivid than now — a time when people really lived, when things really happened. Yet the decade haunts not because of some unrecoverable and unrepeatable confluence of factors, but because the potentials it materialised and began to democratise — the prospect of a life freed from drudgery — has to be continually suppressed.[note]Mark Fisher, Acid Communism. (Unpublished).[/note]

Fisher seemed to want to encourage a community of Lovecraftian Outsiders, unsure of how they arrived at their present situation but nonetheless curious to leave the cloistered world in which they find themselves. Perhaps, like Lovecraft’s Outsider, this is a naïve position — but naïvité is hard to avoid in life at the limits of drudgery. The more immediate problem is that others have already begun to set in motion a similar political project of their own and perhaps it was this similarity that occasioned Fisher’s use of the word ‘egress’.

‘Exit’ was already taken…

2

In many of his writings, particularly on his K-Punk blog, Fisher was never shy about acknowledging the influence of Nick Land on his thought. The two had worked together as part of the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit at the University of Warwick in the late 1990s — a collective of ‘renegade academics’ whose potent homebrew of cybernetics and philosophy, flavoured with a Lovecraftian sci-fi mythos, continues to have considerable occultural influence today. Whilst the group was largely anonymous, always opting for a collective voice, much of its output has subsequently become readily associated with Land as the group’s most infamous member.

Whilst Fisher’s approach to politics seems fundamentally at odds with Land’s — at least in his later writings, the public perception of which has led to Land being quietly blacklisted by a number of publishers — they nevertheless share much in common philosophically.

Just as Thacker wrote of his interest in a philosophy that “enigmatically confronts the horizon of its own possibility”, the shared project of Land and Fisher is arguably one of applying the implications of such a speculative approach — often used to discuss more abstract questions of ontology and metaphysics — to the more immediate concerns of political philosophy.

Fisher’s most famous project, in his book Capitalist Realism, was to explore the notion that the end of the world is easier to imagine than the end of capitalism. Land, in The Dark Enlightenment — his controversial essay on Neoreactionary thought — instead explores the end of democracy as the limit of contemporary sociopolitical thinking.

The initial focus of Land’s essay is exit — a concept that has previously been put to use by thinkers across the political spectrum since the publication of Albert Hirschman’s 1970 book Exit, Voice, and Liberty, but is here given a uniquely Landian twist.[note]See: Albert O. Hirschman, Exit, Voice and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1972)[/note] Similar to egress, Land’s exit refers to both an epistemological and practical exit from hegemonic social structures and belief systems. Land, however, proposes that exit be used against democracy. He writes:

Democracy and ‘progressive democracy’ are synonymous, and indistinguishable from the expansion of the state. Whilst ‘extreme right wing’ governments have, on rare occasions, momentarily arrested this process, its reversal lies beyond the bounds of democratic possibility. Since winning elections is overwhelmingly a matter of vote buying, and society’s informational organs (education and media) are no more resistant to bribery than the electorate, a thrifty politician is simply an incompetent politician, and the democratic variant of Darwinism quickly eliminates such misfits from the gene pool. This is a reality that the left applauds, the establishment right grumpily accepts, and the libertarian right has ineffectively railed against. Increasingly, however, libertarians have ceased to care whether anyone is ‘pay[ing them] attention’ — they have been looking for something else entirely: an exit.[note]Nick Land, The Dark Enlightenment, http://www.thedarkenlightenment.com/the-dark-enlightenment-by-nick-land/[/note]

Land goes on to define the social model he sees as politically desirable with the phrase: “no voice, free exit”, drawing explicitly on Hirschman and Curtis ‘Mencius Moldbug’ Yarvin.[note]See: Mencius Moldbug, “Patchwork: a positive vision (part 1)”, Unqualified Reservations, November 13, 2008, http://unqualified-reservations.blogspot.co.uk/2008/11/patchwork-positive-vision-part-1.html[/note] This formulation describes a non-democratic system of government in which citizens have no ‘voice’ but are free to leave whenever they wish.

Here, a citizen’s relationship to government is made analogous to the relationship between customer and business: customers have no say in how the business itself is run but they are welcome to opt for another competing service provider if they are unsatisfied with their experience. Land describes this model another way on his blog:

Government, of whatever traditional or experimental form, is legitimated from the outside — through exit pressure — rather than internally, through responsiveness to popular agitation. The conversion of political voice into exit-orientation (for instance, revolution into secessionism), is the principal characteristic of neoreactionary strategy.[note]Nick Land, “Premises of Neoreaction”. Xenosystems, February 3, 2014, http://www.xenosystems.net/premises-of-neoreaction/[/note]

What is missing here — and likewise missed by the simplification of “no voice, free exit” — is the temporal complexity of Land’s maneuver. He describes how conservative and reactionary ideologies are made paradoxical in their retreat towards or repetition of what has come before. Neoreaction suggests a new approach to the old — it is a ‘progressive’ ‘conservatism’ that disembowels the meanings usually attached to either of those two words. Land’s exit, in this way, is a movement through these ideologies which, in their cyclonic relation to each other, offer new approaches towards progress and, therefore, time itself in their coupled divergence from the classic liberal model of teleological progressivism.

Here Land, too, invokes the Lovecraftian Outsider — a voiceless shadow out of time driven by exit — in opposition to the political establishment’s Jamesian warnings against the outer edges of this cloistered world. On his Xenosystems blog, with its penchant for abstract horror, Land could not be clearer:

The Outside is the ‘place’ of strategic advantage. To be cast out there is no cause for lamentation, in the slightest.[note] Nick Land, “Outsideness”. Xenosystems, August 1, 2014, http://www.xenosystems.net/outsideness-2/[/note]

Neither Land nor Fisher shy away from the horrors that the traversing of these limits might summon within the human mind. Even though these limits have migrated to the realm of political philosophy, in corners both left and right Lovecraft remains a cogent reference point.

Fisher may have agreed with the strategic advantage of the Outside but, whilst the ends are similar, the means could not be more different.

For Fisher, thinking through the work of Herbert Marcuse, the history of Western art is littered with exit strategies. He presents a leftist instantiation of Land’s Outsider position, challenging the contemporary populist left, that can at best be described as working to a model of all voice and no exit, calling for new attempts at finding exits through other ways of living — attempts that have all too often been neutered by capitalism’s cooptive mechanisms.

The counterculture of the 1960s and ’70s is a prime example of this. Fisher writes that,

as much as Marcuse’s work was in tune with the counterculture, his analysis also forecast its ultimate failure and incorporation. A major theme of [his 1964 book] ‘One Dimensional Man’ was the neutralisation of the aesthetic challenge. Marcuse worried about the popularisation of the avant-garde, not out of elitist anxieties that the democratisation of culture would corrupt the purity of art, but because the absorption of art into the administered spaces of capitalist commerce would gloss over its incompatibility with capitalist culture. He had already seen capitalist culture convert the gangster, the beatnik and the vamp from “images of another way of life” into “freaks or types of the same life”. The same would happen to the counterculture, many of whom, poignantly, preferred to call themselves freaks.[note]Mark Fisher, Acid Communism (unpublished).[/note]

However, Fisher’s is not an anarcho-primitivist position, supporting a return to a time before capitalism and its technologies. His accelerationist position is an advocation of the use of capitalism’s forces to modulate past potentials, transducing them into the future by collectively harnessing capital’s deterritorializing capacities for outside aims and egresses.

Again, it can be argued that this is not so far from Land’s position either, but their arguments pivot on a battle between humanism and inhumanism. For example, Fisher and Land both share an acknowledgement of capitalism’s blobjective tendency to absorb everything it comes into contact with. On his Xenosystems blog, Land notes that the left’s analyses of capitalism — more perceptive than the right’s — remain indebted to the Deleuzo-Guattarian critique that capital “is highly incentivized to detach itself from the political eventualities of any specific ethno-geographical locality, and — by its very nature — it increasingly commands impressive resources with which to ‘liberate’ itself, or ‘deterritorialize’”.[note] Nick Land, “Capital Escapes”. Xenosystems, November 21, 2014, http://www.xenosystems.net/capital-escapes/[/note]

Capital’s stifling of any meaningful exit other than its own remains a central point of contention within many contemporary leftist discourses, particularly in black and queer studies, many of which share Fisher’s attempt to rethink the pessimism of an exit-as-apocalypse ideological default.[note]See, for example, Lee Edelman’s No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive (Durham: Duke University Press, 2004) — notable for its titular challenge to heteronormative temporality — and Denise Ferreira da Silva’s essay “Towards a Black Feminist Poethics: The Quest(ion) of Blackness Towards the End of the World” (The Black Scholar, 44, No. 2, States of Black Studies (2014), 81-97), in which she ponders explicitly black exit strategies: “Would Blackness emancipated from science and history wonder about another praxis and wander in the World, with the ethical mandate of opening up other ways of knowing and doing?” See also, for a more recent consideration of Land’s writing and Afropessimism: Jehu, “Land, Wilderson and the Nine Billion Names of God”, The Real Movement, August 20, 2017, https://therealmovement.wordpress.com/2017/08/20/land-wilderson-and-the-nine-billion-names-of-god/[/note] Land, however, in this framework, doubles down on capital’s deterritorializing capacities, removing any purely humanistic agency and suggesting that, at present, exit is the sole prerogative of capital and not of those caught up in its rhythms, pulsions and patternings.

Whilst Land seems to suggest that we must channel the inhumanist exit of capital as an already-existing path towards exteriority, Fisher argues for a collective channelling of Lovecraftian aesthetics leading to the formulation of new cultures, which remain the only way for the left to egress — and, in order to do this, it is essential that the left learn from the countercultures that have come before.

To return to our Lovecraftian metaphor: if Land is an Outsider, having looked in the mirror and identified with the inhumanism of capital, Fisher is rather hoping to collectivise, organising an Acid Communist Cthulhu Cult of Outsider-worshippers. His focus on the aesthetic challenge is no doubt influenced by his subcultural affiliations. What are Goths if not Outside-worshippers who already live amongst us? However, even this subculture has been subsumed within capitalism — commodified, its vague political potentials have long been neutralised.

Elsewhere, the Alt-Right‘s repeated exclamation that they are the ‘new punk’ preempts any renewed channelling of the 1960s and ’70s — a cry that is so often met with derision, despite punk’s well-documented on-off political and aesthetic flirtations with fascism.

Aesthetic questions of exit are further complicated here. Even post-punk, which Fisher wrote about at length and which he acknowledged as his primary cultural influence, flirted with fascist imagery. Writing on Joy Division’s aesthetic appropriations of images of the Hitler Youth on their debut EP, An Ideal for Living, he writes:

The Virilio / Deleuze-Guattari analysis of Fascism, remember, maintains that Fascism is essentially self-destructive: a line of pure abolition. As such, Fascism is just the name for one more variant of the Romantic lust for the Night when all identity, all individuation, is subsumed in ‘an ecstatic aestheticized experience of Community’ (Zizek).[note]Mark Fisher, “Nihil Rebound: Joy Division,” K-Punk, January 9, 2005, http://k-punk.abstractdynamics.org/archives/004725.html — here Mark is quoting from Slavoj Žižek, The Plague of Fantasies (London: Verso Books, 2009)[/note]

Here again community emerges as central to processes related to the channelling of the Outside. Fisher’s invocation of communism is obviously communal but even Land’s model of ‘exit pressure’ surely relies on a collectivised desire for exit within a given system if that pressure is to have any weight at all. Different means, similar ends.

Whilst Fisher does not advocate an anti-democratic position like Land does, his recommended practices are certainly extra-democratic. Capitalism cannot be ‘voted out’ but a big enough change to the cultural status quo could make it politically redundant.

This double-pincer of ‘community’ — with its equally dystopian and utopian potentials — grounds many takes on the ‘question of Communism’ as it has been discussed in recent years by continental philosophy. Whereas fascism seems to hold self-destruction as its central motif, much writing on communism holds the destruction of the Other as a folded destruction of the Self. As Maurice Blanchot writes in his book The Unavowable Community:

To remain present in the proximity of another who by dying removes himself definitively, to take upon myself another’s death as the only death that concerns me, this is what puts me beside myself, this is the only separation that can open me, in its very impossibility, to the Openness of a community.[note]Maurice Blanchot, The Unavowable Community, trans. Pierre Joris (Barrytown: Temple Hill Press, 1988), 9.[/note]

To engage with this Openness, this Opening, is precisely to ‘egress’.

3

Maurice Blanchot’s comments on community were initially written in response to Jean-Luc Nancy’s 1985 essay on Bataille, The Inoperative Community, and this response triggered a correspondence between the two which would last for a number of decades.

Nancy was to have the final word.

In late 2001, just prior to Blanchot’s death in 2003, Nancy wrote the preface for a new edition of The Unavowable Community. Detailing the history of their conversation, Nancy describes the essence of “community” (which he had — he admits — first failed to account for) as “the space between us — ‘us’, remaining in the great indecision where this collective or plural subject stands and stays condemned never to find its own proper voice.”[note]Jean-Luc Nancy, “The Confronted Community”, trans. Jason Kemp Winfree, in The Obsessions of Georges Bataille (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2009), 25.[/note]

What Nancy describes here — now in line with Blanchot’s own thought — is a paraontological community that is constituted by an unknowable and unavowable bond that dares us “to think the unthinkable, the unaccountable, the intractable of being-with, but without subjecting or submitting it to any hypostasis”.[note]Ibid., 27[/note]

It should be noted that Nancy is writing here just one month after the events of September 11th 2001. Such an event of international trauma is “all at once a confrontation and an opposition, a coming before oneself so as to challenge one’s self, so as to part within one’s being a gash that is the condition of this being”.[note]Ibid.[/note]

This gash is presented here as a primal wound. It is not created by tragedy — tragedy is rather a finger stuck through it, making us all too aware of its presence. For Nancy, the events of 9/11 instigated a colossal questioning of the self — not unlike the horrors of the Second World War that influenced Bataille’s original writings. Whilst one nation or people may have suffered the brunt of a particular attack, the event nonetheless highlights a rupture within all of us, requiring a paraontological questioning of the collective subject that extends far beyond national and cultural ‘communities’ and into the ever-elusive outside ‘us’.

Nancy continues: “the sudden offensive strike that has taken in a stunning figure with the collapse of the symbol of global commerce (and therefore of exchange, of relations, and of communication) presents itself, or wants to present itself, as a religious confrontation, with fundamentalist monotheism, on the one side, humanist theism, no less fundamentalist, on the other”.[note]Ibid., 28[/note] What is interesting is that this same topic became the site of Land and Fisher’s final convergence.

Dual essays posted on the Urbanomic website at the end of 2016, just a month before Fisher’s death, contended with the communal wounding of the terror attacks of November 13th 2015, in which 130 people were killed and almost 500 injured when bombers and marauding gunmen attacked the streets of Paris, most catastrophically targeting an Eagles of Death Metal concert at the Bataclan music venue in the 11th arrondissement.

Both Land and Fisher are here responding, more specifically, to Alain Badiou’s 2016 essay on the attacks, Our Wound is Not So Recent.[note]Alain Badiou, Our Wound Is Not So Recent: Thinking the Paris Killings of 13 November, trans. Robin Mackay.(Cambridge: Polity Press, 2016)[/note] Whilst Fisher “calls for a new politics to counter the decadence of capitalist realism”, Land “reconfigures the battlefield of the future, and plays devil’s advocate for globalised capitalism”.[note]Mark Fisher, “Cybergothic vs Steampunk”, Urbanomic, 2016, https://www.urbanomic.com/document/cybergothic-vs-steampunk-response-to-badiou/; Nick Land, “Sore Losers”, Urbanomic, 2016, https://www.urbanomic.com/document/sore-losers/[/note] Nevertheless, both arguments find themselves in orbit of community and its outside.

“Capital is nothing if it is not parsimonious”, Fisher writes, “and for the last thirty years it has sustained itself by relying on readymade forms of existential affiliation”.[note]Mark Fisher, “Cybergothic vs Steampunk”.[/note] For Fisher, ISIS is most certainly an abhorrent death cult, but it is a death cult that should nonetheless be recognised and taken seriously for its success in offering some young Muslims — the West’s Outsiders du jour — something that capitalism never can.

What ISIS forces into capitalism’s global currents is an extremist neoreactionary community — “a cybergothic phenomenon which combines the ancient with the contemporary (beheadings on the web)”[note]Ibid.[/note] — that appears incompatible with the West’s hegemonic moral structures and culturally Judeo-Christian belief systems.

As an example of “the rising tide of experimental political forms [appearing] in so many areas of the world”, ISIS presents us with an extreme and potently unthinkable example of a people “rediscovering group consciousness and the potency of the collective” outside the reach of capitalism, and neoliberal (post)colonialism more specifically.[note]Ibid.[/note]

For Fisher, the left must find its own community, a new community, that opposes such abject violence whilst nonetheless sharing with ISIS a dual resistance against and utilisation of the technologies of coercive capital. Their violent example must not occasion a rallying behind the symbol of Western capitalism under siege. This new community must instead harness the exacerbation of capitalism’s failures that those fighting for an Islamic State continue to violently reveal for us.

It is Land who demonstrates this entangled problematic most damningly. He similarly takes on the limitations of capitalist collectivities but, by contrast, directs his polemic towards Badiou’s universalised ‘Frenchness’ as the symbol of modernity’s failures.

When Badiou proclaims that ‘Our wound is not so recent’, we are compelled to ask: How far does this collective pronoun extend? A response to this question could be prolonged without definite limit. Everything we might want to say ultimately folds into it, ‘identity’ most obviously. Whatever meaning ‘communism’ could have belongs here, as ‘we’ reach outwards to the periphery of the universal, and thus (conceivably) to the end of philosophy.[note]Nick Land, “Sore Losers”.[/note]

With his focus on a nationalistic identitarianism, Badiou stifles his own reach towards an outside that the terror attacks themselves have instigated. Land writes, and Fisher also suggests, that the horror of the question of community, taken as Blanchot radically intended it, must include ISIS.

Any Western conception of ‘us’ that resists the folding of that which we deem outside ‘us’ — as ISIS are both judged and choose to be — is to remain trapped within the damned and damning subjectivity of contemporary neoliberalism. To insist ‘we are not like them’ and ‘they are not like us’ is to double down on our failures.

Land continues:

French identity, radically conceived, corresponds to a failed national project. Is it not, in fact, the supreme example of collective defeat in the modern period, and thus — concretely — of humiliation by capital? It is the way the ‘alternative’ dies: locally, and unpersuasively, without dialectical engagement, dropping — neglected — into dilapidation. It can be inserted into a limited, yet not inconsiderable, series of identities making vehement claim to universality without provision of any effective criterion through which to establish it. When frustrated by the indifference of the outside, such objective pretentions tend to turn ‘fascist’ in exactly the sense Badiou employs.[note]Ibid.[/note]

He concludes:

The ‘liberation of liberalism’ has scarcely begun. None of this is a concern for Badiou, however, or for the Islamists. It belongs to another story, and — for this is the ultimate, septically enflamed wound — as it runs forwards, ever faster, it is not remotely theirs.[note]Ibid.[/note]

This wound is all of ours, even when the collective ‘our’ is radically extended into infinity. Modernity, however, is not a cold and unyielding surface of polished glass — at least not for the West. It is obfuscated; fogged.

To be confronted by ISIS is precisely to look in the mirror and not recognise the inhuman face of modernity looking back. The accelerated destruction of ISIS, occasioned — the West hopes — by the fall of Mosul, is to only prolong our own self-destruction.

Fisher concludes:

The growing clamour of groups seeking to take control of their own lives portends a long overdue return to a modernity that capital just can’t deliver. New forms of belonging are being discovered and invented, which will in the end show that both steampunk capital and cybergothic ISIS are archaisms, obstructions to a future that is already assembling itself.[note]Mark Fisher, “Cybergothic vs Steampunk”.[/note]

As Land, too, has consistently insisted, whether the trajectory is towards communism or any other political future, the unthinkable must be thought and recognised and this will never be without risk:

“To find ways out, is to let the Outside in.”[note]Nick Land, “Quit”, Xenosystems, February 28, 2013, http://www.xenosystems.net/quit/[/note]

![]()

[/note] Always obsessed with digestion, Paracelsus was quick to focus discussion upon the supposedly eupeptic properties of the water. He praised carbonated spring water as “driv[ing] away gout, and mak[ing] the stomach as strong in digestion as that of a bird that digests tartar and iron”.[note]Walter Pagel, Paracelsus: An Introduction to Philosophical Medicine in the Era of the Renaissance (Karger, 1982), 26.[/note] Imagining the ‘occult’ powers of the earth’s chthonic healing laboratories — fizzing forth at the surface in this natural medicine — Paracelsus became enthused: he attempted to artificially recreate the fizziness, but met with no success. It was, as we have seen, only with his apprentice, van Helmont, that this effervescence first became the subject of reverse engineering, thus opening the pathway to the industrial and globalised production of soft drinks. Speculating even that the acidity of the spa waters held some occult connection with gastric acid, Paracelsus and van Helmont enthusiastically opined that carbonated waters were better than almost any other medicines. Bolstering an enduring fascination with the fizziness that seeps from the planet’s chthonic depths — stretching back to Hippocrates, and becoming more popular throughout the Middle Ages — the iatrochemical tradition helped to fully entrench the connection between fizz and eupepsia in the public consciousness.

[/note] Always obsessed with digestion, Paracelsus was quick to focus discussion upon the supposedly eupeptic properties of the water. He praised carbonated spring water as “driv[ing] away gout, and mak[ing] the stomach as strong in digestion as that of a bird that digests tartar and iron”.[note]Walter Pagel, Paracelsus: An Introduction to Philosophical Medicine in the Era of the Renaissance (Karger, 1982), 26.[/note] Imagining the ‘occult’ powers of the earth’s chthonic healing laboratories — fizzing forth at the surface in this natural medicine — Paracelsus became enthused: he attempted to artificially recreate the fizziness, but met with no success. It was, as we have seen, only with his apprentice, van Helmont, that this effervescence first became the subject of reverse engineering, thus opening the pathway to the industrial and globalised production of soft drinks. Speculating even that the acidity of the spa waters held some occult connection with gastric acid, Paracelsus and van Helmont enthusiastically opined that carbonated waters were better than almost any other medicines. Bolstering an enduring fascination with the fizziness that seeps from the planet’s chthonic depths — stretching back to Hippocrates, and becoming more popular throughout the Middle Ages — the iatrochemical tradition helped to fully entrench the connection between fizz and eupepsia in the public consciousness.