DAY 5. 🅱🅰🆂🅸🅻🅸🆂🅺: Menstrual Chaotics and God’s Ectopic Pregnancy

And so, we see that Caleb Bradham, in both inventing and branding Pepsi, invokes a tradition that stretches directly back to 16th century iatrochemical experiments. In advertising his product as an ailment for peptic ulcer, Bradham was drawing upon Priestley’s use of carbonation as a cure for scurvy, which — in turn — was an uptake of van Helmont’s discovery of gas and Paracelsus’s pioneering interest in balneological healing. Pepsi thus emerges directly from the alchemical-archeus tradition. Pepsi is alchemical. It also emerges, therefore, from the same tradition Milton used to fashion the metaphysical structure of Paradise Lost, a tradition he was deeply familiar with. Nevertheless, despite the ancient connection between fizz and eupepsia, it does not aid digestion: it makes it worse. Rather than lending us the hyaline peristalsis of the angels — for whom “what redounds transpires […] with ease” — it aggravates purging and superfluity. And so, as Walter Charleton wrote in his translations of van Helmont, “we (as Nature) advance to the DEPURATION or Defecation”: we advance, that is, to nature’s inherently “excrementitious ways”.[note]Walter Charleton, Natural History of Nutrition, Life, and Voluntary Motion, Containing all the New Discoveries of Anatomists and Most Probable Opinions of Physicians, concerning the Oeconomie of Human Nature: Methodically Delivered in Exercitations Physico-Anatomical, (London, 1659), 91.[/note]

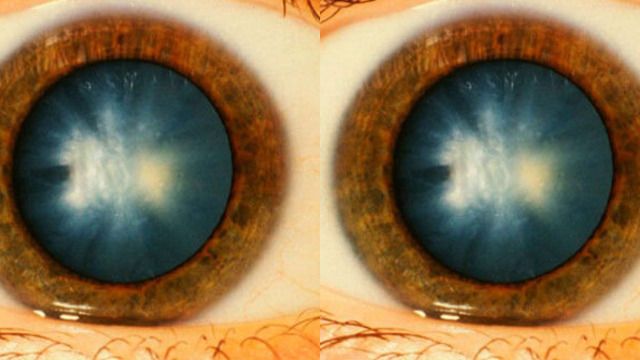

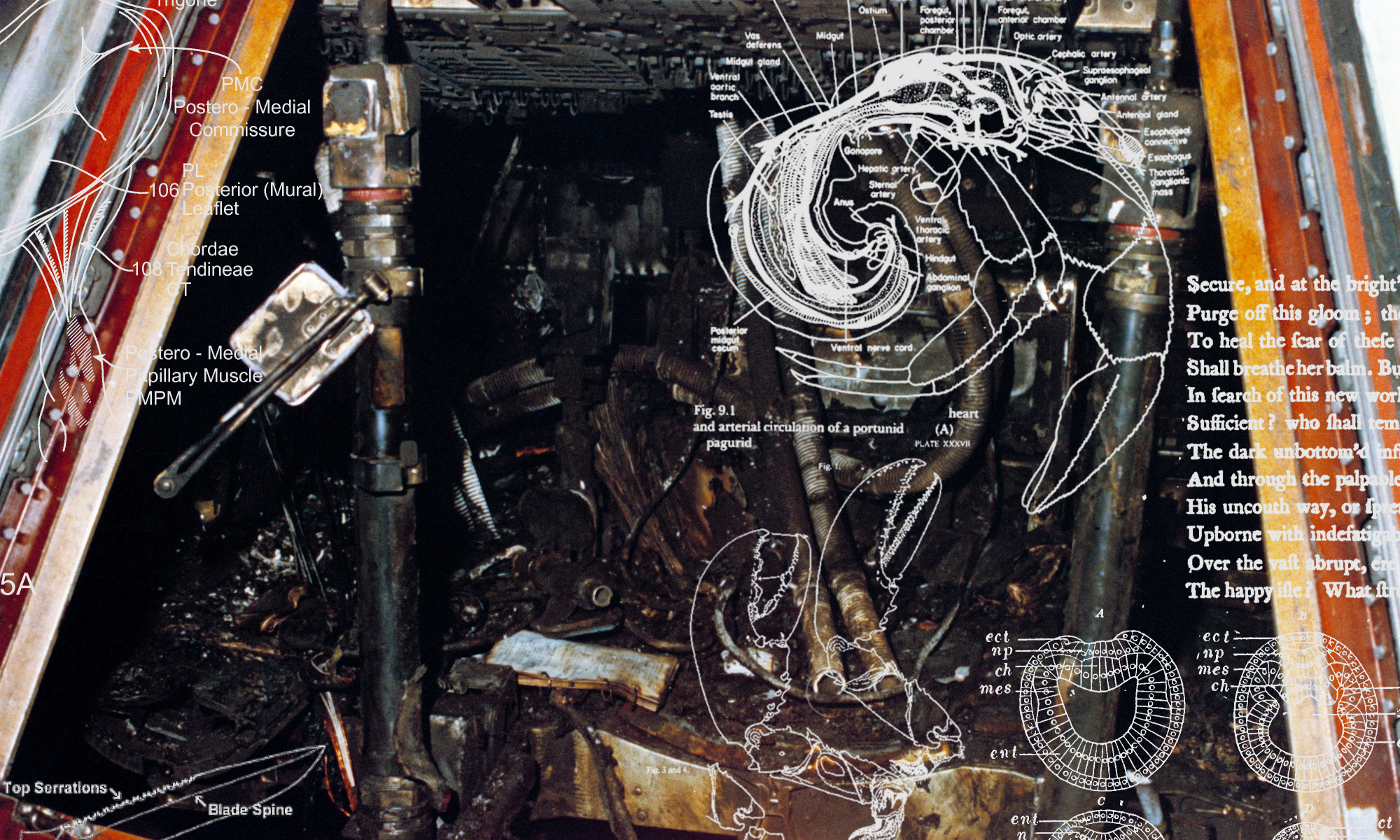

With all digestion there must be excrement (just as with all knowing there must be a transcendental barrier). And this applies at the highest level: it applies to the digestive tract of Milton’s cosmos itself, to the very archeus. There is, it seems, some dimension of matter that exceeds even God’s anabolic assimilation into divine forms. Excrement is — ontologically — insuperable. Angels still experience matter that “redounds”; nigredo is necessary for alchemical purification; even the glassy hyaloides are at risk of “depuration” from gutta serena.[note]Indeed, ‘hyaline’ has come — in modern usage — to denote the superfluous matter in degenerative medical conditions.[/note] As we have already glimpsed, the universe of Paradise Lost contains a surprising amount of scatology for a seemingly ultra-Christian theodicy: nature itself lets off two violent barrages of flatus upon the consumption of the Apple’s “intellectual food”. Elsewhere, we see Satan’s ‘anal cannons’: waging “intestine war in heaven” with artillery engines fashioned from the “entrails” of the empyrean, complete with “hideous orifice[s]” gaping “wide” [PL; vi.259, 517, 577]. In Book I, we hear of the “subterranean wind” belching from “thundering Ætna”, whose “entrails […] leave a singed bottom all involv’d / With stench” [PL; i.231‐7].[note]One cannot but imagine that gout-riddled Milton knew all about how a “singed bottom all involv’d / With stench” felt.[/note] This sprawling epic undeniably embeds the poetic traces of the tortured flatibusque that Milton himself complained of. Appropriately, it appears that Milton (probably as his health deteriorated) came progressively to reject his earlier promotion of the ideal of a perfect digestive tract: writing on transubstantiation in his De Doctrina, he explains that “if we eat flesh, it will not remain in us, but (to be utterly frank) after being digested […] will finally be voided”.[note]De Doctrina, 751.[/note] Even holy rituals cause shite. Further to this, we see that this same axiomatic irreducibility of excrement applies to God himself, and his own alimentary canal: i.e. it applies to Creation. When mapped in this way (i.e. within an archeus-inflected cosmological schematic), the axiom of the inevitability of excrement becomes recast as a troubling ability for matter to exceed even divine planning. This arises as a mutation of hylomorphism, one that Paracelsian philosophy encrypted as the idea of ‘chaos’ or ‘tartar’.

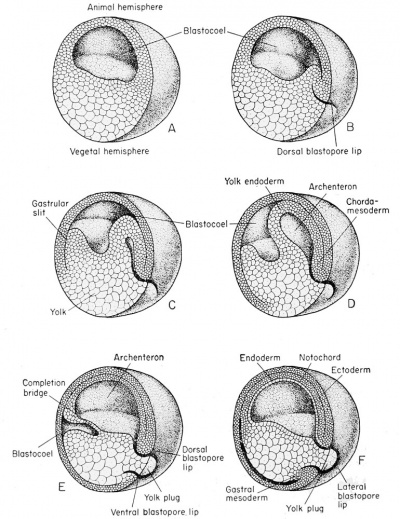

Within the ancient Aristotelian schema, ‘matter’ is merely the blank potency of being or non-being that forms take on (this is why it is properly thought of as merely the empty capacity — the receptacle — for accepting forms). It is thus nothing without forms: matter is more of a modal category than any kind of substratum or ‘stuff’. Matter is only actualised with the imposition of forms: which — for Aristotle and later scholasticism — are identical with intelligible structure. As a direct consequence, matter extricated from all intelligibility was entirely unthinkable.[note]This is not the same as idealism of the Berkelian variety (indeed, this was only possible much later). Rather, it is merely the claim that being is intelligible because it itself has a logical or propositional structure. The mutual entwining of actuality and intelligibility.[/note] Matter could not, in this schema, be self-actualising: which is to say that it could not be regarded as fully actualised outside of any relationship with mental categories. In a specific sense, then, all matter was caused by intellectual structures (and could not be thought of as self-causing). Hence, the collocation of matter with passivity or receptivity: an assumption that heavily informed Aristotelian gynaecology, wherein ‘hyle-’ was compared with menstrual fluid (as feminine and passive receptacle) and ‘-morphe’ was compared with seminal fluid (as masculine and form-giving nous). Moreover, it was precisely this tradition that inspired Paracelsus in his (deeply misogynistic) quest to remove the female from the reproductive process through the production of an alchemical homunculus via in vitro incubation: the ideal of an artificial (and, specifically, man-made) lifeform, which would be gestated only from pure seminal nous, thus — so it was thought — unalloyed of all dirty traces of feminine corporeality. Purged of feminised base matter, the male-created homunculus would be a creature of pure intellect. (Paracelsus, it appears, may have actually been a hermaphrodite: hence, possibly, his Promethean obsession with surpassing sexual hylomorphism/dimorphism.)[note]cf. William R. Newman, Promethean Ambitions: Alchemy and the Quest to Perfect Nature, (University of Chicago Press, 2005), 197.[/note]

Nevertheless, aside from closely following the Aristotlean tradition in this gynaecological sense, the 16th-17th century iatrochemists were also beholden to subsequent, late medieval developments in the conception of ‘matter’ that had entirely transformed the ontological entailments of commitment to a hylomorphic model. In short, late medieval developments had forged a conception of matter as self-actualised and self-actualising outside of any relation to intelligibility. Thus, it could now finally take on its modern denotation of lethal externality (beforehand, matter could not be conceived of as ‘outsideness’, because — with matter and intelligibility considered as perfectly uniform — there could properly be no ‘outside’ in this novel, modern sense). Only here, with the idea of matter as causing itself outside of mental categories, could it become the alien otherness it is conceivable as today. This potentiated the idea of matter as an ‘outside’.

How did this happen? In short, during the late-medieval fortification of the Christian voluntarist tradition, the scholastic hylomorphic tradition mutated. God was split between the so-called potentia absoluta and potentia ordinata or between his absolute freedom and his constrained intellect — an anonymous and unthinkable/unthinking power and an intelligible and bureaucratic form. The argument ran that the former, the potentia absoluta, could not be constrained by anything… including our ideal categories. As such, it must be conceivable that things could become fully actualised beyond any relationship to mental structure or to conceivability. Thus, where matter was previously only ever conceivable in relationship to mind — and as caused by ideal structures — it now became thinkable as self-actualising outside of any relationship to mind: this is the same as saying that matter became thinkable as self-causing and thus as auto-producing. Hence, the fear of ‘matter without forms’ as something that is self-developing, self-directing, auto-productive, cancerous, etc. The prospect of ‘matter without forms’ transforms from the inert nothing of mere receptivity/passivity to the superlative nothing of an auto-productive zero. In the absence of the top-down anabolism of bureaucratic forms, hyle could switch into malignant self-direction: synecdochal revolt.

This was all a direct consequence of splitting God into an unconstrained power and an ordinate planning: for the crushingly absolute and unconditioned nature of the former smuggles in the ability for things to exceed even the decree of divine planning. God’s uncontrollable Id could recrudesce, dissolving his rightful Mind. Indeed, this likely represents the intellectual historical birth of the modern notion of the unconscious as an internal splitting (alienation). Through this mutation, the collocation of ‘matter and receptivity’ could eventually mutate fully into ‘matter and excessiveness’. With realism (in the full modern sense), matter’s distance from mind inverted from passive nothingness to superlative nothing: not the zero of reality, but the reality of zero. Materiality, by gaining autonomy from intelligibility, became thinkable as anonymous unthinkable power. Crushing anonymous omnipotence. Winnowed from intelligibility as its condition of actuality, matter could now be considered as pure rebellion and revolt against thought (and, thus, also God’s own divine planning). And, emerging from within (immanently), it is rebellion in the precise Satanic sense. Indeed, the fear of auto-production flows from here: matter without forms, exceeding all central planning, all assimilation, all divine eupepsia. Matter as total deregulation. Voluntarist force[note]Voluntarism can carry varying connotations. As a more modern political category, it has carried implications of the limitation of freedom to humanist models of agency. However, in its elder origins in the medieval, speculative excesses surrounding omnipotence, it actually first emerges as a conception in opposition to this later development. Voluntarism as pure freedom, being power beyond limitation, is the destruction of the structures and confines that necessarily delimit and individuate a human subject. Pure power tends towards impersonality. This more eldritch notion of sovereignty is utterly destructive regarding the modern humanist subject, yet, with delicious irony, the former lies at the source of the latter.[/note], defined by its distinction from intellect, accommodates a fear of the Real as self-causing alienness (as something that can exist entirely outside of its thinkability, because it causes itself), thus opening up the way for the horror of synecdochal revolt, as matter becomes self-directing and self-catalytic malignance, looping back into itself and surpassing any top-down rule (be it from Divine fiat, human norms, natural law, or the conditions of its representation and control). And so, matter could become the superlative nothing of an apoptotic hylomorphism rather than the inert nothing of orthodox hylomorphism. (Blindness not as asthenia of sight, but as the excess voluptuousness of darkness visible.) Thus, retrofitted onto the gastrointestinal system of alchemy, we arrive at acephalic excremental revolt. The belly usurps the head. (Just as Pepsi-addiction tends towards living-to-drink, rather than drinking-to-live.)

This heterodox ‘rotten hylomorphism’ was registered variously in the alchemical tradition as tartar, chaos, and nigredo: the excessive and irreducible excrement of the archeus; the blackened, goopy residue left over after fermentative and alchemical reactions. That which exceeds subtilisation or distillation into forms, and yet — as prima materia — remains the unruly condition of all ‘object specificity’.[note]PRIMA MATERIA = 232 = DOUBLE PINCER[/note] Zero becomes both departure and death. Thus, the incessant collocation of ‘womb’ and ‘tomb’ in Early Modern poetics.[note]”Zero is immense.”[/note] Indeed, Paracelsian gynaecology held that, in the absence of male seminal forms, female menstrual fluid would eventually come to feed back into itself and become a runaway self-propelling process of mutative self-development. Menstruation without semen — just like matter without forms — becomes self-feeding chaos. (Again, chaos has now inverted into the overabundance of essences, rather than their asthenia: excess rather than absence.) Arising from folklore tradition, it was generally held that basilisks were the product of wombs that, in the absence of regular male insemination, had looped into runaway auto-generation. Roko’s basilisk is God’s period.[note]Indeed, auto-production — because it is self-causing — is thus intimately tied up with both the demonic (as reproductive nothing) and, also, with temporal insurrection. Pepsi is basilisk-like because, as the avatar of auto-producing chaos, it comes to coerce itself into existence through the looping flows of tartareous base matter.[/note]

This language of apoptotic hylomorphism and chaotic menstrual excess makes its way directly into Paradise Lost, surrounding the crushingly ambiguous and troublingly central figure of Chaos. Milton describes this massa confusa of “embryon Atoms” as “the womb of nature and perhaps her grave” [PL; ii.900, 911]. Zero is tomb and womb. Material zero, as self-looping overabundance, is excess rather than receptivity: granted total autonomy from mentality, matter becomes self-causing (just like demonic zero). In Comus this is described as the “waste fertility” of an overflowing and superfluous Nature.[note]Comus, in Milton: The Complete Shorter Poems, ed. J. Carey, (Longman, 2007), ll.728.[/note] And this links directly to Milton’s extreme denial of ‘nothing’: for, in saying that nothing cannot be no thing, Milton unwittingly galvanises and evaginates it, making it into a powerful something, mutating baseline 0 into an overwhelming ontological force. He writes, in De Doctrina, “darkness was by no means nothing”:

[for if] darkness is nothing, then God surely created nothing by creating darkness, that is, he did and did not create, which is a self‐contradiction.[note]De Doctrina, 289.[/note]

Nothing can’t exist; even purest darkness is something. Thus, the necessitous nature of the infamous “darkness visible” [PL; i.36]: lacunae are excess not absence; violent externality not inert passivity. This even applies to blindness (via its direct connection to flatulence and excrement). Milton describes his blindness with the language of superfluity rather than absence. In the letter to Philarus, Milton writes that, as his

sight was completely destroyed […] abundant light would dart from my closed eyes [and] colours proportionately darker would burst with violence and a sort of crash from within; but now pure black, marked as if with extinguished or ashy light, and as if interwoven with it, pours forth. Yet the mist which always hovers before my eyes both night and day seems always to be approaching white rather than black.[note]De Doctrina, 867-71.[/note]

This aggressive blindness literally is darkness visible. (Significantly, Milton claims that even “pure black” tends, in his failing eyesight, towards “white”, and indeed, at the time, it was known that white was the accumulation of all of the spectrum.)[note]Spinoza, who specialised in ‘glassy essences’, wrote that “a white surface [is one] which reflects all rays of light”. Spinoza, The Correspondence of Spinoza, A. Woolf, (Russell & Russell, 1966), 393.[/note] Thus, seeing everything paradoxically includes within itself total blindness (insofar as seeing everything includes ‘seeing’ nothing, staring straight into the void). The ‘truth’ of sight is blindness, just as the lethal dose of life or truth is death. As such, it is telling that even in Milton’s early optimistic descriptions of perfect perceptive-digestive assimilation, the implication of scatological excess is not far away: the epistemological purity of “Elegy V” is smeared by the poet’s mention that, in seeing everything, he also sees the “Tartara caeca” — ‘caeca’ denoting ‘unseen depths’, but also the ‘blind gut’ or ‘large intestine’.[note]”Elegy V”, ll.20.[/note] Indeed, as we are about to see, “tartar” holds a special place in both Miltonic and Paracelsian cosmology as the rebellious shite of the universe. Nevertheless: because nothing is not a negation but a superlative, even blindness is a special type of seeing: it is seeing too much, it is looking straight into the blinding darkness of the universe’s tartara caeca, the appropriately named blind gut — the solar anus[note]PEPSI CHAOS = 201 = SOLAR ANUS[/note] — of the cosmos. Milton, in short, blinded himself because he looked too far into the fizzing, dyspeptic nigredo of Chaos.

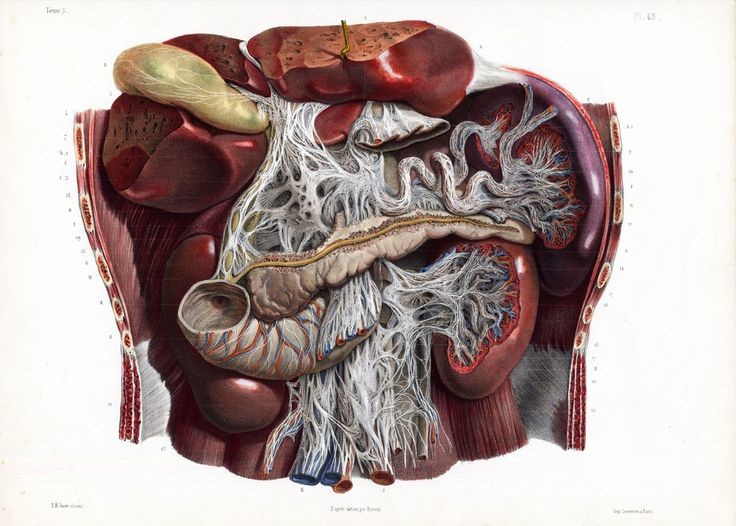

And so, we arrive finally at Miltonic Chaos. Chaos is the ultimate hypostatisation of the auto-productive tendency latent within matter: the tendency to metastatise into its own self-selecting end-orientation — rather than the holy direction of divinely-sanctioned totality — thus coming more and more to threaten the primacy and integrity of the ‘host’ whole. Chaos is ontological cancer and crap. As Milton decrees, it is “neither sea, nor shore, nor air, nor fire / But all these in their pregnant causes mixed” and it is likewise simultaneously “strait, rough, dense, or rare” (Chaos fizzes) [PL; ii.912-3, 948]. Again, it is ontological overabundance not ontological paucity. As such, whilst wading through this superseding elemental indigest, Satan simultaneously “swims or sinks, or wades, or creeps, or flyes” — there is no medium-specificity here [PL; ii.950]. Qualities and essences overflow rather than withdraw. Thus, despite being hermeneutically linked with ‘ontological deficiency’ (because of its position as an allegorical figure), Milton’s Chaos is total superfluity. Chaos is the excremental pregnancy — the menstrual chaos and “waste fertility” — of God and Creation: the excrement of the cosmic archeus, it is that which fails to be incorporated (digested) into the happy hylomorphism (the agreeable working of the stomach-soul) within God’s intestinal system. Chaos as cosmic dyspepsia.

For Paracelsus, any archeus’s excrement is something called “tartar”. For, upon inspecting the black, thick, putrefied deposits inside wine casks (called ‘tartar’, ‘argol’, or ‘lees’), Paracelsus saw a tangible analogy for Chaos itself. The product of fermentation (i.e. digestion), wine lees was an alchemical analogy for universal excrement. It would come to be deployed by Paracelsus as symbol for the indivisible remainder of digestion. Accordingly, as physician, Paracelsus diagnosed this necrotic, blackened matter as the same stuff that built up within bodies and caused mortality (namely, in intestinal ulcers, gallstones and other such maladies). This tartar — whether in wine casks or human guts — came, ultimately, from what Paracelsus identified as the “superfluity” of all matter. For Paracelsus, following the tendency of a rotten hylomorphism, matter both in metabolism and perception always exceeds. Keeping this in mind, we now turn to the moment of Creation itself as depicted in Paradise Lost. Here Milton describes how God “as with a mantle did invest” the “rising world” as he comes to separate it — via divine dialysis — from the “waters dark and deep”, from the dark liquid abyss prior to creation. Just as the alchemists had done incessantly before him, Milton cannot help but give this watery filtration a gastric-scatological twist.

His brooding wings the spirit of God outspread

And vital virtue infuse’d, and vital warmth

Throughout the fluid Mass, but downward purg’d

The black tartareous cold infernal dregs [PL; vii.235-8]

(Note that “vital warmth” was associated, in the hylomorphic-gynaecologic tradition, with the formative and nous-giving sperm — as contradistinguished from the “cold” base matter of menstrual hyle.) The implication here — via the deployment of the Paracelsian word “tartareous” to describe the “infernal dregs” — is unavoidably excremental.[note]In his edition of Paradise Lost, Flannagan annotates this passage claiming divinity ‘seems to excrete the regions of Hell’ (545). Fowler, in his edition, disclaims it as ‘not scatological’ (403), following Kerrigan; Kerrigan, however, does indeed admit it as ‘fecal’, ‘excremental’ and ‘in the anal mode’, in The Sacred Complex: On the Pyschogenesis of Paradise Lost (Harvard University Press, 1983), 69.[/note] Indeed, others amongst Milton’s contemporaries, those also schooled in iatrochemical lore, had reached similar conclusions: Thomas Tymme had reported that Moses “tells us that the Spirit of God moved upon the water” and therefore by “God’s Halchymie” the “corrupt stinking feces, or dross matter” was brought, in a digestive process of filtration, to the “christalline cleernes” of the firmament.[note]Thomas Tymme, The Practise of Chymicall, and Hermeticall Physicke, for the preservation of health. Written in Latin by Iosephus Quersitanus, Doctor of Phisicke. And translated into English, by Thomas Timme, minister (London, 1605), i.[/note]

God shits out the creation.

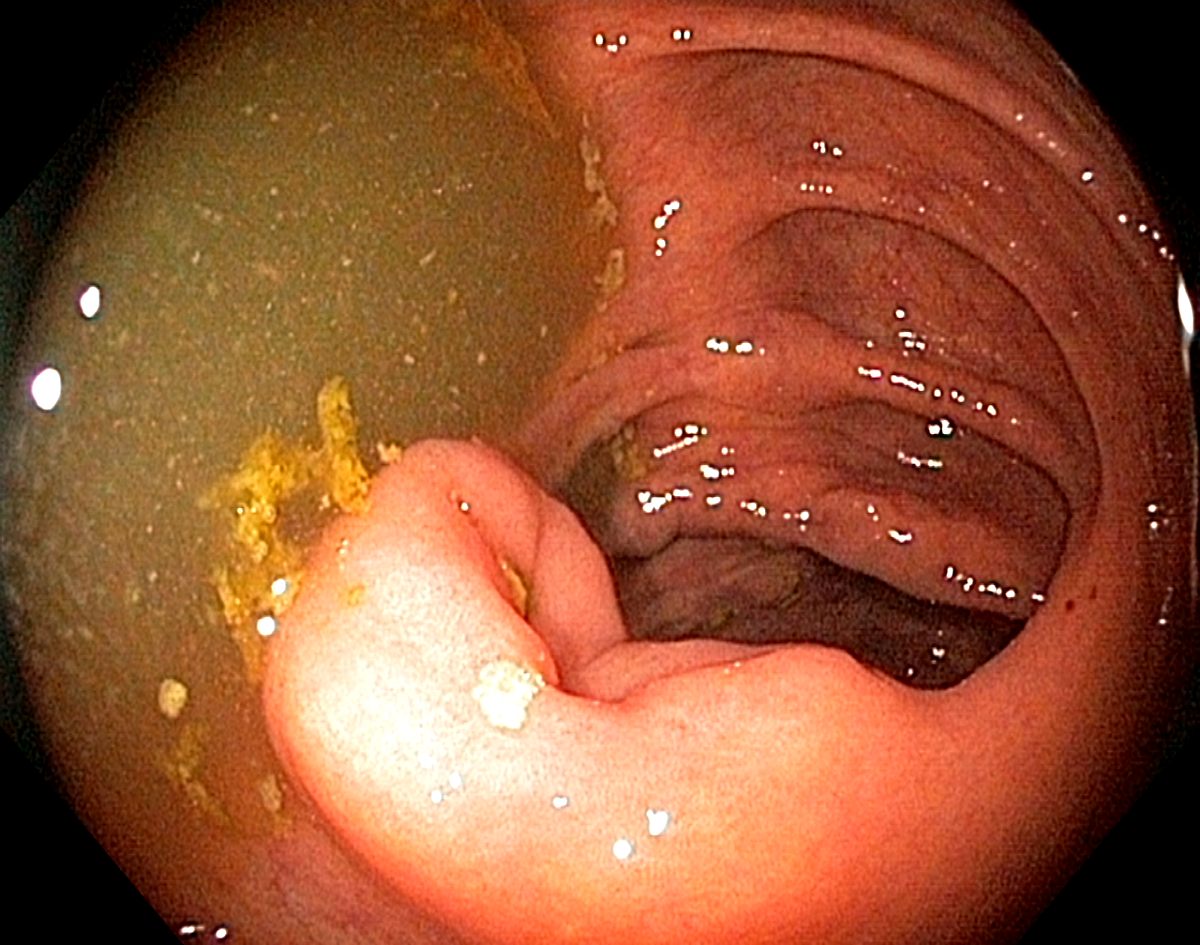

There is simply no way that Milton would have been unaware of the resonances he was weaving here. For Milton would have known all about tartar due to his own physical ailments. Contemporary medicinal understanding held that ulcers were tartareous growths: ontologically adjacent to the superfluities left over from fermentations. Paracelsus himself was a prolific and influential writer on this topic: for him, ulcers — like Satanic revolt — were malignant excrescences of auto-production, of synecdochal usurpation (as such, Milton would have understood his microscale splanchnic putrefaction in much the same way as the macroscale ‘intestine strife’ of heavenly revolt). As already explored in this series, Milton likely had a peptic ulcer. Moreover, a major symptom of this deadly ulcer would have been ‘melena’: the “passing of dark tarry faeces” containing blood.[note]OED.[/note] Identical in appearance to the wine tartar or ‘lees’ found in the bowels of brewing vats: the muck that Paracelsus had nominated as symbolic of the chaotic nigredo of creation. Thus, one must emphasise the striking fact that Milton — no stranger to ‘tartareous’ faeces and the medical literature surrounding it — chose to describe the very act of Biblical Creation as itself “tartareous”.

Significantly, in the chronotemporal layout of Paradise Lost, this cosmogenic bowel evacuation precedes Genesis’s separation of the waters. The vitreous filtration, then, was preceded by divine diarrhoea. Milton, elsewhere, writes that the hyaline separation was a “mere minister” of Creation, for “the spirit only brooded on the surface of waters which had already been created”.[note]De Doctrina, 287 — my emp.[/note] Thus, we note that nature’s crystalline aspect is ontologically posterior to its faecal aspect — just as Crystal Pepsi was merely a camouflaged version of the obsidian original. As such, the core paradox arising from the laws and fundaments of Milton’s miniature universe comes into full focus: all things — even the seemingly perspicuous firmaments — are sedimented, condensed, or coagulated out of base Chaos. With an ambiguity that resounds throughout his entire universe, Milton presents his Chaos as equally antecedent and as equally infinite as God: this “infinite Abyss” [PL; ii.405] is “Ancestor […] of Nature” [PL; ii.896]; and as “eldest Night” [PL; ii.894] it is properly the “Womb of nature” [PL; ii.911]. And so, we have located this as the originary trauma attendant upon the internal workings of Miltonic cosmogeny and metaphysics: this is the secret of the Miltonic chronotope. Beginning in an excremental ‘purging’ of tartareous prima materia from the godhead, the universe forever encases within itself the excessive capacity of matter: that which refuses (and routes around) imposition and regimentation. As such, the default state of matter is not obedience or formfulness: the gut floras of creation do not harmonically “sing their great Creator” by default, but only by the coercion of constant stratification. The default state of matter is usurpation and escape (hence, the constant risk of ontic synecdoche). And this means that the risk of chaotic relapse quivers at all ontological echelons as indwelling potency. Consequently, this process of divine digestion is continual and unceasing. Because Chaos is the baseline and default, God must keep anabolizing the “Lump” of increatum in order to stop it relapsing into primordial formlessness. Thus, excretion and dialysis are condemned to inexorability.

This can be seen in Milton’s depiction of Limbo as an immune-sewage system for the tumours of hylomorphism. That is, all the excessive and teratological forms of the world pass through Limbo — as the colon of Creation — before being excreted into the Outside. All “unaccomplished works of nature’s hand / Abortive monstrous or unkindly mixed / Dissolved on earth” pass into Limbo, as Milton envisions [PL; iii.455-7]. Moreover, Limbo is contiguous with Chaos as the nethermost port of Creation: described as a “boundless continent” with “ever-threatening storms […] blustering around [PL; iii.425-6]. And, as such, its purpose is clearly to crap out all the destabilizing matter needing to be excreted from right creatio. As such, Limbo is seen to contain a peristaltic procession of “embryos and idiots”, alongside Enoch’s Nephilim, born of ancient miscegenation “betwixt the angelic and human kind” [PL; iii.462]. Continuing the deep connection between metabolism and epistemology, Limbo also therefore contains theological and philosophical excrescences too: “relics, beads” and “dispenses [or] bulls” are farted out by the “violent cross wind” [PL; iii.489-92]. (Limbo, thus, is a cosmological limbic system: it filters out dangerous forms and ejaculates them into chaos.) These internal specters of chaos-relapse are pushed outwards, and they “pass the planets seven, and pass the fixed” [PL; iii.481], before their “abortive” purge into the Outside. This is the anus of the universe. As such, we see how everything — at all ontological levels — expresses the potential to collapse back into effervescent, liquid blackness. In short, the matter of Chaos’s “outrageous […] sea” is imposed with God’s forms to become the eupeptic “crystalline ocean” that we witness as the “new-made World”, and yet the “extremes / Contiguous” will always loom underneath [vii.212, 272–3]. (Identical, again, to the fact that consumers could taste that Crystal Pepsi was a lie because the taste of saccharine blackness lurked beneath perspicuous appearance.) It is the cosmic unconscious of ontological dyspepsia — the “tartara caeca” or “blind gut” — rumbling and gurgling beneath the glassy “hyaline”: and, like “Acheron”, it is “black and deep” and fizzy [PL; ii.578]. Quite simply, Chaos is not defeated but only temporarily repressed by the forms of divine central-planning: like a liquid or a gas under pressure it always struggles to release itself and to fizz forth from the depths.

So, we turn, once more, from the birth of the cosmos, back to the bubbling birth of Pepsi Cola. Immediately, one notes the resonances between the wine tartrates that Paracelsus describes and Pepsi-Cola: blackened and tartareous, wine lees were often also sugary and sweet. Certainly, it has become a memetic contagion of late to unveil this viscous blackened mass as the true state of Pepsi Cola (YouTube videos abound depicting the results of boiling cola).[note]https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=boiled+in+pepsi[/note] As a form of modern alchemy, one ferments the cola into a similar chemical state as the tartrates that inspired Paracelsus to describe the “superfluity” latent in all matter. Subsequently, we note the crucial fact that van Helmont first discovered carbon dioxide — thus initiating the chain of events that led to the invention of Pepsi Cola — precisely by studying tartar. Spurred on by Paracelsus’s obsession with this particular substance (and the centrality it came to enjoy in his mentor’s metaphysics), he studied at great length the fermenting process of wine. Observing the emanations from wine vats, he first came to the conclusion that they were releasing “gas sylvestre”. Thus, just as Priestley would later invent soft drinks through studying the fermentation process of beer, carbonation was first discovered by van Helmont through his inspection of the ferment of wine.[note]Indeed, beer brewing produces an equivalent tartrate substance to wine lees, referred to as ‘trub’.[/note] Pepsi’s discovery arises out of tartareous muck. And the occult synchronicities continue to surge backwards as Pepsi-Chaos loops into its own historical creation: for the very word ‘gas’ derives directly from ‘chaos’.[note]SOFT DRINK = 197 = PRIME CHAOS [/note]

Because of the link Paracelsus had made between tartareous ferment and the prima materia, van Helmont — from the very beginning — connected carbon dioxide and carbonation with chaos. To carbonate something was to impregnate it with a chaotic essence. And accordingly, ‘chaos’ is invoked in ‘gas’ through the phoneme ‘g’, which in van Helmont’s native Dutch sounds exactly like the ‘kh’ in the Greek ‘khaos’.[note]It also shares resonances with the word ‘geest’ or ‘geist’ (for spirit or ghost).[/note] (Furthermore, it holds resonances with Dutch words for fermentation.) With this coinage, van Helmont meant to signpost the fact that CO2 gas is — precisely — chaos. Thus, the relation to chaos and indigestion is philologically embedded within the word ‘carbonation’. For, as we have already seen, ‘indigest’ was itself an ancient substantive for chaos. Moreover, ‘chaos’ itself — coming from the Greek verb ‘to yawn’ — is related to Indo-European roots for the term ‘gape’: echoing the orifices that pumped the world with excremental entropy-chaos in the first place. Helmont continued to deepen this link, explaining that his “gas” is a form of “halitus”: meaning ‘wind’ or ‘emanation’, from which our term ‘halitosis’ derives. Chaos thus refers not only to prima materia but also to the gassy emanations of gaping orifices. Excrement is chaotic; chaos is excremental. “Every flatus in us is a wild Gas”, he wrote, “stirred up by digestion from meats, drinks and excrements”. Carbonation — the secret behind soft drinks — is originally discovered through alchemical study of the chaotic effluence of the cosmos. In naming Pepsi Cola after dyspepsia, Caleb Bradham was ventriloquised by this rich tradition that arcs back across occult history.[note]CALEB BRADHAM’S DRINK = 307 = PEPSI COSMOGENY[/note]

Thus, we are forced to conclude that Pepsi is intimately related to the Chaos of Milton’s Paradise Lost (sharing their genesis and inspiration in the gastric-iatrochemical metaphysics of Paracelsus and van Helmont), and insofar as both Pepsi and Chaos are auto-productive, they allow for the temporal looping (auto-production tends towards self-causation, which is a form of retrochronic exchange) that reveals the occult retrocausal pathways, opened up to us via this alchemical knowledge, by which Pepsi ventriloquises Miltonic Chaos, just as Miltonic Chaos prefigures Pepsi.

Tomorrow: ‘Sugar & Zero, Milton & Böhme: the Dyspeptic Abyss of Theogony’

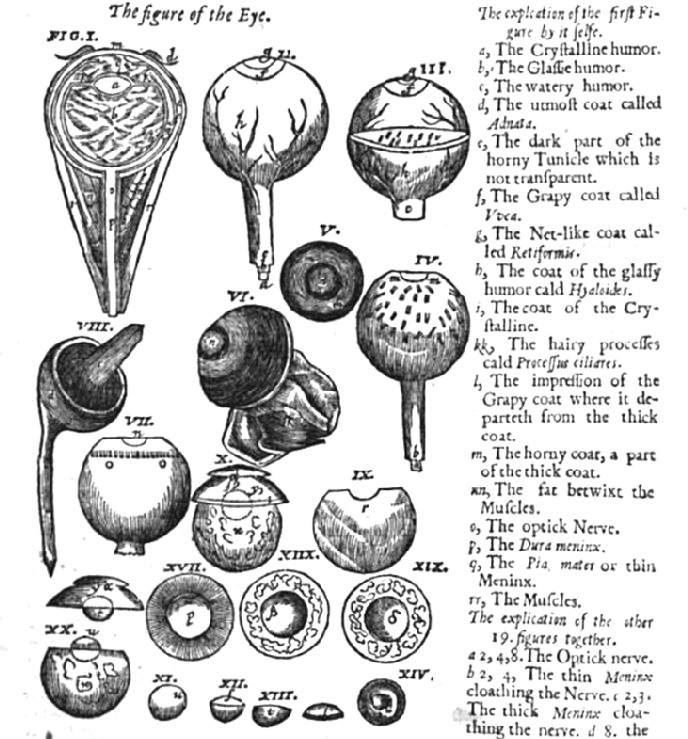

[/note] Milton describes how God “as with a mantle did invest / The rising world of water dark and deep, / Won from the void and formless infinite”: he provides it with a protective skin, a form-suffusing “mantle”. As such, through wrapping the entire created universe in a “clear” liquid sack, this “crystalline ocean” becomes purposed with protecting the cosmos from the “loud misrule” of the Chaos that lies just beyond it [PL; vii.269, vii.271].[note]Chaos is, thus, analogical to the ‘energetic excess’ that Freud describes as facilitating the epithelial individuation of the originary vesicle, in his account of metapsychological abiogenesis, in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (Penguin, 2003).[/note] It is therefore a prophylaxis against an external chaoticism, and — as such — a spheroid cosmic immune system and metaphysical life support.[note]Cf. Peter Sloterdijk, Globes: Macrospherology, Volume II: Spheres (Semiotexte, 2014).[/note] A crystallic womb. Certainly, pre-Copernican cosmology is precisely a cosmology of ‘immuno-containment’, and containment takes place across similar mediums (containment implies infinite divisibility); thus, to stress the ‘containment’ of the sublunary within the “hyaline”, as Milton does, is to impart some of the latter’s “crystalline” perfection to our own world. In other words, through its vitreous dialysis, this primum mobile acts as a vesicle purposed with separating Creation from Chaos: the happy harmony of this amniotic encasement — a placental harmony, therefore, between sublunary fundament and crystalline firmament and achieved through the shared medium of crystal perspicuity — announces the pre-lapsarian stability of Paradise Lost’s “new-made world”. Nonetheless: just as there was something wrong at the heart of the Crystal Pepsi venture, predestining it to fall, so too is there a blackening necrosis within this pellucid womb of Milton’s fictional cosmos.

[/note] Milton describes how God “as with a mantle did invest / The rising world of water dark and deep, / Won from the void and formless infinite”: he provides it with a protective skin, a form-suffusing “mantle”. As such, through wrapping the entire created universe in a “clear” liquid sack, this “crystalline ocean” becomes purposed with protecting the cosmos from the “loud misrule” of the Chaos that lies just beyond it [PL; vii.269, vii.271].[note]Chaos is, thus, analogical to the ‘energetic excess’ that Freud describes as facilitating the epithelial individuation of the originary vesicle, in his account of metapsychological abiogenesis, in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (Penguin, 2003).[/note] It is therefore a prophylaxis against an external chaoticism, and — as such — a spheroid cosmic immune system and metaphysical life support.[note]Cf. Peter Sloterdijk, Globes: Macrospherology, Volume II: Spheres (Semiotexte, 2014).[/note] A crystallic womb. Certainly, pre-Copernican cosmology is precisely a cosmology of ‘immuno-containment’, and containment takes place across similar mediums (containment implies infinite divisibility); thus, to stress the ‘containment’ of the sublunary within the “hyaline”, as Milton does, is to impart some of the latter’s “crystalline” perfection to our own world. In other words, through its vitreous dialysis, this primum mobile acts as a vesicle purposed with separating Creation from Chaos: the happy harmony of this amniotic encasement — a placental harmony, therefore, between sublunary fundament and crystalline firmament and achieved through the shared medium of crystal perspicuity — announces the pre-lapsarian stability of Paradise Lost’s “new-made world”. Nonetheless: just as there was something wrong at the heart of the Crystal Pepsi venture, predestining it to fall, so too is there a blackening necrosis within this pellucid womb of Milton’s fictional cosmos.

[/note]). Just as the planets are ‘contained’ within the life-support of the supernal realm, so too are our bodies, vouchsafed via the microcosm-macrocosm concordance of eyeball and firmament. ‘[T]here is a double firmament, one in the heavens and one in each body, and these are linked by mutual concordance’[note]Walter Pagel, Joan Baptista Van Helmont: Reformer of Science and Medicine (CUP, 2002), 99.[/note] This semantic entanglement between eyeball-strcuture and cosmos-structure is, unsurprisingly, ancient. As the Talmud, which Milton was familiar with, puts it:

[/note]). Just as the planets are ‘contained’ within the life-support of the supernal realm, so too are our bodies, vouchsafed via the microcosm-macrocosm concordance of eyeball and firmament. ‘[T]here is a double firmament, one in the heavens and one in each body, and these are linked by mutual concordance’[note]Walter Pagel, Joan Baptista Van Helmont: Reformer of Science and Medicine (CUP, 2002), 99.[/note] This semantic entanglement between eyeball-strcuture and cosmos-structure is, unsurprisingly, ancient. As the Talmud, which Milton was familiar with, puts it: