J-F. Lyotard[note]Jean-François Lyotard, “Petite mise en perspective de la décadence et de quelques combats minoritaires à y mener”. In Dominique Grisoni, ed., Politiques de la philosophie, 121-153. Paris: Grasset, 1976. This is the first English translation of this work.[/note]

translated by Taylor Adkins

Critique, minorities

Let’s begin with a sort of warning to say that we will seek to avoid the traditional “critical point of view”. Critique is an essential dimension of representation: in the order of the theatrical, it is what stands “outside”, with the exterior incessantly situated in relation to interiority, i.e. the periphery relative to the center. A so-called dialectical relation is established between the two; this relation does not safeguard the autonomy of critique, not by a long shot.

Two possibilities orient this relation: either the periphery conquers the center (first destiny of critique: through reversal and takeover); or the center situates the periphery and uses it for its own benefit, for its internal dynamics (second destiny: the putting into opposition). Thus, there are two cases of glorious death.

There are inglorious deaths. To name a few: the destruction of the peasant movement in Germany begun by the Frankenhausen massacre in May 1525; the liquidation of the Donatists and Circumcellions in Roman North Africa in the 4th century; that of the Cathars by the “French” armies; that of the Commune by Versailles and the Reich; that of the Catalan communes and committees by the Francoist armies and by the communist political police in 1937; the destruction of Hungarian communism in 1956; the liquidation of the Czech movement in 1968; the massacres and deportations of the Native American nations in the 19th century by the Yankees, etc. I am omitting many instances, and I am certainly omitting more “important” ones: but who can make that judgment call? This is a question of minorities crushed in the name of Empire. They are not necessarily critical (the Native Americans); they are indeed “worse”, they do not believe, they do not believe that there is an identity or coalescence between the Law and the central power, they affirm another space formed by a patchwork[note][English in the original — TN].[/note] of laws and customs (we now say cultures) that lacks a center. In this sense, they are polytheistic, whatever they may have said and thought about themselves: to each nation its authorities, without any having universal value or totalitarian reach.

These struggles are struggles of minoritarians that seek to remain minoritarian and to be recognized as such. Yet nothing is more difficult: they are transformed into new powers, into oppositions of His Majesty — or into mass graves. They are interpreted, i.e. inscribed in imperial space as tensions arising from the periphery, in imperial discourse as dialectical moments, in imperial time as apocalyptic pronouncements. In this way, they are depotentialized from the start. By banning their cultures, their dialect, one seeks to destroy their affirmative force, the “perspective” (in the Nietzschean sense) that each of these struggles traces — in a time that is not cumulative. (In this regard, capitalism faithfully fulfills the imperial tradition.) It is therefore necessary to insist on this: the force of the movements of their perspective does not come from the fact that they are critical, i.e. the fact that they are situated in relation to the center. They do not intervene as peripeteias in the course that Empire and its idea follow; they constitute events.

Yet, under further scrutiny, these movements reveal something that never stops being produced on the small or even microscopic scale in the everyday life of “the little people”. Minoritarian affirmation never stops being produced, even when it is imperceptible. It is subtle and refined, even before it manages to be said and enacted in the public sphere: the billions of unvoiced deliberations by women in the home, well before the MLF[note][Mouvement de libération des femmes, which arose in France after the events of May ’68, was adjacent to the Women’s Liberation movement in America, and questioned the legitimacy of the overarching dominance of patriarchal society — TN].[/note]; the billions of little tragic, heinous, woebegone shames suffered, well before the MLAC[note][Mouvement pour la liberté de l’avortement et de la contraception, which pushed for legal abortion in France and eventually dissolved after achieving its objective in February 1975 — TN].[/note]; the thousands of humorous and oft-repeated stories in Prague before the “Prague Spring”; the millions of little meeting rituals through mimicry and graffiti in semi-public places for homosexuals prohibited from the social scene, well before the FHAR[note][Front homosexuel d’action révolutionnaire, which was founded in 1971 and continues to strive to bring visibility to and fight for the rights of LGBT individuals — TN].[/note]; the billions of isolated or collective aggregates of laborers in workshops and offices, a repulsive matter that can only pass into syndical discourse disguised as negotiable demands. This reality is not more real than that of power, of the institution, of the contract, etc., it is just as much so; but it is minoritarian; thus, it is necessarily multiple, or if one prefers, always singular. It only occupies grand politics, on the same surface, but otherwise.

In what follows, as in every minoritarian movement, it will easily be able to be shown that there is a critical aspect, that this discourse repeats critical forms. But what is hidden there is an affirmative position. In the Marxist sense of critique, the negative is privileged. It is held to be an active capacity that can awaken, move, and “bring the masses to action” (to use a stereotype). In other words, it possesses what is commonly acknowledged to be an essential revolutionary virtue: the pedagogical function. In critique, the negative is the dynamic element of conviction, since it educates by destroying the false. However, what must be perceived here is a poorly disguised Socratism. And this is precisely what we are breaking with (albeit the idea of rupture is in all regards a naïve idea), i.e. with a tradition of thought that counts on the effectiveness of the negative, that praises the force of conviction, and that seeks to incite the awakening of consciousness. If theoretical and practical thought continues to imagine itself as pedagogy, then it necessarily repeats these aforementioned traits. To put oneself “on the side of” the affirmative supposes that one abandons the categories of “illness”, “deviation”, “degeneracy”, “decay”, etc. These categories are prejudices, stereotypes; they fall back on the conception of an organism whose calling is to be perfect but whose present state is that of perversion, degradation, and infantilism. The task of the political then consists in restoring to it the perfection that is its own.

Deepening the decadence of the True

We need to reflect on the idea of decadence by taking up a trait that Nietzsche notes in his manuscripts for the Will to Power.

As Nietzsche says, there is indeed a decadence of societies. But it vacillates. It neither adopts a linear course nor a continuous rhythm: it procrastinates. Or instead, there is a procrastination of decadence that is a part of decadence. On the one hand, decadence acts (obviously in its kinship with nihilism) as a destruction of values, notably of the value of truth; and, on the other hand (which is a movement contemporaneous with the first), it works toward the establishment of “new” values. Thus, we have a panicked and pathetic nihilism, for which nothing has value[note][The phrase “plus rien ne vaut” can also mean that “nothing is valid anymore” and/or that “nothing is worth anything anymore”. The translation above is in light of the discussion of Nietzsche and the destruction of values, but these other meanings are just as appropriate and are implied at the same time — TN].[/note] anymore, and an active nihilism that responds: nothing has value anymore? too bad, let’s continue in this direction. The latter is on the side of destruction. The former is the return of faith, the recurrence of an obstinate belief in the unity, totality, and finality of a Meaning. Therefore, the value of truth, which is certainly displaced, nonetheless persists through the discourse of science and its reception.

Nietzsche has clearly seen this restoration of faith on the outskirts of scientificity. One no longer believes in anything, and yet something remains behind: scientific ascesis. It is the school of suspicion, of distrust, because nothing is ever definitively established; but this distrust, which thoroughly traverses the practice of science, contains an act of trust that is renewed each time in the value of labor, i.e. with the goal of knowing and dominating. Trust, which is masked in the critical spirit, maintains activity and thought in the belief that the true is the most important thing. It is certainly no longer the truth itself that is revealed, but nonetheless the happiness of societies and of individuals remains attached to a better knowledge of reality.

Platonism persists today in this way: the prejudice that there is a reality to be known. One distrusts everything, except distrust. One must be prudent, so they say, but what could be more imprudent than prudence?

There are thousands of examples, both elevated and trivial, of this vigorous belief in the true. For example: intellectuals always believe in economic, social, political theory; they expect from it a decent knowledge of realities; they think that without it a just (effective and ethically positive) social transformation cannot ever be produced. The most honest intellectuals attribute to Marxism or to the forms of discourse that borrow from certain parts of its lexicon and syntax this double privilege of being par excellence the language that suspicion takes and that escapes from all (“unavoidable”) suspicion. Here is a shorter example: certain scientists do not hesitate to present “science” as the only reason to live that survives the disintegration of values — thus proposing themselves as new candidates to take over from the clergy. Here is an equally banal example: the importance granted by the culture of the media to scientific works in the form of their spectacular results, but also in the form of roundtables between famous researchers. Even though these researchers publicly express their doubts, their suspicions, and their skepticism regarding their own activity, and even though they nevertheless attest to the decline of the value of truth, especially where it is supposed to persist intact, nothing much changes: the mass-media apparatus, including its spectators, merely turn this into a number of features that highlight certain heroes faced with daunting tasks. The heroism of the will to knowledge for the betterment of life remains a certain value that spans the whole gamut of the forms of trust (of the trust in distrust). One last example: what the American scientists call the new gnosis.[note]Raymond Ruyer, La Gnose de Princeton, Fayard, 1974. [At the time of writing this, Lyotard did not yet know that Ruyer had written this work in order to capitalize on a trending interest in France concerning American scientists; thus, this work is actually a hoax, insofar as it claims to delineate the beliefs of a Princeton cohort of scientists, but it allowed for Ruyer to better disseminate his ideas in a way that he perhaps thought he could not have done if he were claiming to write on his own behalf. It was one of his last but easily his best-selling work—TN].[/note] Certain astrophysicists and biologists are seeking to establish a sort of discourse derived from the paradoxes that stem from the results of their science, a discourse that would be able to envelop these results and explicate them. Through its own humor, the endeavor is obviously seeking to reconstitute certain values of security, which are the very same values that have served to cover over and suppress nihilism since Plato.

Decadence consists in a double movement, in an ongoing hesitation between the nihilism of incredulity and the religion of the true. It is not a process of decay[note]Le pourrissement des sociétés [The Decay of Societies], special issue of the review Cause commune, U.G.E., 10/18, 1975.[/note], which is a univocal process that arises from a biological model of the social, and it is not a process that is dialectical in its most rarefied Marxist sense. Nietzsche instead indicates a movement on the spot that, on one side, exhibits the nihilism that was until then hidden by values and, at the same time, covers over this nihilism with other values. In this regard, science seems at best to satisfy this double requirement: everything must be examined, but not the duty to examine — which is simply conflated with “thought”.

Procrastination arises from this contrariety in movement; decadence does not take the form of a degeneracy. It would be necessary to say that it has lasted since Platonism and that it has never stopped since. And, as Nietzsche emphasizes in Twilight of the Idols, remedies, therapeutics, philosophy, politics, and pedagogy are an integral part of it. In one swoop, in a single perspective, it is “decided” that humanity is sick and that we are starting to want to heal it.

Here is a political path: to harden, to deepen, to accelerate decadence. To assume the perspective of active nihilism, not by remaining at the simple (depressing or admiring) evidence of the destruction of values: to get one’s hands dirty in their destruction, to go ever further into incredulity, to fight against the restoration of values. Let us travel far and quickly in this direction, let us be undertakers in decadence, let us accept, for example, the destruction of belief in truth in all its forms. This is a serious matter for us, who claim to be not just intellectuals, but still to be “on the left”[note][Translating “de gauche” as “on the left” is an approximation; in actuality, the phrase can be appended to any noun (for example, Parti de Gauche/The Left Party) in order to function as the adjective “left” — TN].[/note], i.e. guarantors of the true. It at least requires that we abandon our faith in the value of the position of our own discourse, of theoretical discourse, and of its function of true discourse or of discourse in view of the true.

Science between power and inventiveness

Let me add a short note here. To those who will not fail to retort: “These are all abstractions; science functions de facto, and it never stops obtaining the most incisive results”, we ask that they go interrogate the state of the sciences.

For about ten years, the scientific milieus directly implicated have been posing the question of their existence: what is it that we do?[note]Various works are the symptoms of what I am advancing. From memory, I am only citing one (which is among the most interesting): Autocritique de la science, by A. Jaubert and J.M. Levy-Leblond, Seuil, 1973. This book has been reedited recently in the collection Point.[/note] This is a question that remotely surpasses the simplified version, provided by the mass-media apparatus, of: what purpose does it serve? what usage can we make of our discoveries? etc. Instead, it signifies: how could we know what we say is true? In all simplicity, the man of science admits that what is called verification is taken up again by a certain sort of operativity. Effectively, science invents statements that satisfy certain formal requirements, and these statements must be able to be transcribed into practical and experimental dispositifs[note][There is no perfect way to translate the word “dispositifs” into English: it means “arrangements”, “set-ups”, “lay-outs”, but also “operations”, “plans”, “devices”, “frameworks”, etc. Thus, it runs the gamut from the concrete to the abstract, depending highly on its context. Here, it is transliterated for expedient reasons as well as to synchronize with Iain Hamilton Grant’s translation of Libidinal Economy (Grant provides a nice explanation for how Lyotard uses this word in the introductory glossary to that work — TN].[/note] whose effects can be observed and predicted, if possible. These effects are certain modifications of one or several variables, with the other variables being supposed as defined; they are capable of being observed and described. Understood in this way, “scientific research” is not that of truth, but of efficiency, or controlled, predictable operativity. The truth consists in the fact that the following is produced, along with the statements themselves: 1) a theoretical unity of the set of statements and 2) a meta-unity of this theoretical unity with the data set. However, when the state of the sciences is examined from the sole point of view of scientific theory (unity no. 1), what is witnessed are bundles of often independent and sometimes incompatible statements whose sole condition of coexistence is not even a hidden unity (of the last instance type) but an immediate criterion of operativity. In our view, contemporary science discovers a space of discourse and practice whose form is ultimately not at all defined in terms of conformity with an object, nor even with a formal principle of unity or compatibility of statements between them, but, whatever it may be in truth, is attached to a constant and minimum criterion of efficiency. The political and theoretical discourse of philosophers, sociologists, epistemologists, and other doxographers — for example, post-Althusserian Marxists or post-Levistraussian structuralists — is also very much alongside what scientists know about themselves, of what they have learned concerning their practice. Alongside, because it maintains traditional requirements: a unified, centralized discourse that gives way to the totality of the givens of the scientific field (“democratic centralism” in matters of knowledge). In its everyday existence, that of several million minoritarian “researchers”, science has no relation with this.

Thus, when it is a question of the decadence of the idea of truth, it is harmful to remain content on the level of habitual critique, which denounces science on behalf of capital, but the problem of the efficiency of scientific statements in themselves must be posed in terms in which it is scientifically defined today: prediction due to the exact control of variables.

An example becomes prominent as if by itself, the immediacy of which is the political transcription of the requirements of Skinnerian psychology by the Centre: that of the treatment of German prisoners, who are known as the RAF (Red Army Faction). The dossier published in France on their detention conditions[note]A propos du procès Baader-Meinhof, Fraction Armée Rouge: de la torture dans les prisons de la R.F.A. Collection Bourgeois poche, 1975.[/note] relates extremely interesting facts in this regard. We learn that the militants of the RAF have, among other things, been submitted to so-called “sensory deprivation” experiments. The subjects are placed in a cell that has been transformed into an achromatic environment in which all sounds have been neutralized (a dispositif of white noise: the individual no longer hears anything, not even the noises of his own body, the beating of his heart, his breathing, the gritting of his teeth, etc.; his cries are also inaudible). In the medium term, the result of the experiment is the death of the subject: this is the case of Holger Meins; in the short term, as professor Jan Gross, one of the scientists responsible for the important progresses made in this field, says: “this aspect [the possibility of influencing someone through isolation] can certainly play a positive role in penology (the science of punishment), i.e. when it is a question of rehabilitating an individual or a group, and when the utilization of such a unilateral dependence and of such a manipulation can effectively influence the process of rehabilitation”.[note]Baader-Meinhof, ibid., p. 71. It is good to know that these researches are led by the Sonderforschungsbereiche [Collaborative Research Centers] of the University of Hamburg. The same Institute of Hamburg has participated in 1973 on various days organized by NATO dedicated to aggressiveness. Besides the United States, England, Canada, and Norway, Poland was also represented there. Are these the faux pas of socialist science? Or is all science capitalist? Or is it socialism that is capitalist? Or rather, is it not above all a question, in every discourse of knowledge, under all regimes, of the same imperial madness?[/note]

Yet what is particularly revealing in what Jan Gross says is that the conditions of sensory deprivation allow us to obtain a guinea pig that is situated in the optimal conditions of experimentation, i.e. because the non-controllable factors that can act on the subject have become negligible (almost null) in the course of the experiment. Total isolation, such as it is practiced on the members of the Baader group, thus offers the possibility of mastering the data set of the experiment. The modifications that will be obtained on the guinea pig-individuals will exclusively arise from the stimuli provoked by the experimenter.

Here we have a formidable perfecting of the techniques of torture, which stirs up disgust, hatred, and terror. And there is still something else: the old dream of the human sciences is realized: to constitute a totally controllable object; thus, since it is a question of men, the dream of obtaining subjects in which the capacity for retaliation is completely neutralized, i.e. the capacity to grasp information by which they are bombarded and whose effects they are distracted by. It is then that we rediscover the question of efficiency. For to define the efficiency of a scientific statement exactly comes down to being able to read and describe a result whose variables, which were present from the start of its production, have been in their totality, without any interference by an uncontrolled variable, mastered by the researcher. However, with this example of the treatment to which the RAF group is submitted, we are delineating a sort of congruence between a certain idea of scientific efficiency and a certain idea that is much more than the idea of repression, an idea of the control of data in an advanced and liberal capitalism: bodies are these “data”. There’s no need for Hitlerian panoply, as this is all done under a democratic regime.[note]Better than anyone else, Claude Lefort has written on the delirium of homogeneity applied to the social “body”; cf. his commentary on The Gulag Archipelago in Textures, 10-11, 1975.[/note]

But science is in no way reducible to this centralist totalitarian aspect, an aspect through which it is congruent with the discourse of knowledge and with the intrinsic imperialism of capital. From the start, there are mathematics in which the question of the control of variables is not posed, where, on the contrary, since time immemorial the question posed is that of the invention of new concepts, that of making operative in the form of appropriated symbols the obstacles themselves, which are met with the desire to operate: inventions of numbers, of spaces that overturn natural mathematics. It surely must not be said that these quite sophisticated formations escape from an imperial usage by principle; but it is certain that they go hand in hand with the decadence of a centralist, homogeneous conception of escape, as in topology, or a centralist, countable conception of number, as in number theory. Thus, these formations introduce a capacity of imagining and operating that passes beyond the constraints that were previously held to be divine, natural, essential, or transcendental.

And then, alongside this artistic mathematics, and sometimes due to it, an artistic physics, an artistic logic is established, in which the requirements of unity, totality, and finality are simply abandoned. In certain parts of contemporary science, the unthinkable gives rise to thought, to coherent discourse: the space of neighborhoods and of limits anterior to all measure; antiparticles; bizarre logics: the bizarre logic of Stanislaw Leśniewski allows us to demonstrate the proposition: The section of the book is the book.[note][The word “tranche” here could also refer to the “edge” of a book. What is important to understand is the advances that Leśniewski made specifically in mereology, the theory of part and whole, along with contributions to protothetic (the logic of propositions and their functions), ontology (the logic of names and functors of arbitrary order, a theory of classes attributed specifically to Leśniewski himself), and metalogic (the study of properties of logical systems). His work also involved reintroducing Frege’s language/metalanguage distinction in order to diagnose the liar’s paradox, which Lyotard will address in an upcoming section — TN].[/note] It is not sufficient to notice that these inventions move us quite positively toward the traits of the unconscious Freud described negatively; they must inspire our imagination and our practice of an unmeasurable sociopolitical space that is not mediated by a countable center or that is not homogeneous and also our imagination and our practice of a non-Aristotelian logic, as A.E. van Vogt said.

In this function, science never stops being itself, and it continues to submit to the rule of operative fruitfulness: the new symbol must be defined, the new proposition must be demonstrated, the effects of the new law must be observable in reproducible conditions. But the input must make the inventive imagination of researchers reverberate. Then the meaning of the condition of efficiency changes. Instead of accentuating the control of variables (like aggressiveness), the latter — submitted to formal requirements, logical requirements, axiomatic requirements, and the requirements of experimental dispositifs — merely serves as a means for inventiveness. Science is not the discourse of effective knowledge, which claims to find in its conformity to “reality” the confirmation of its value; it is creative of realities, and its value consists in its capacity to redistribute perspectives, not in its power to master objects. In this regard, it is comparable to the arts.

In the arts as well, there is a whole expenditure of energy dedicated to defining the means that render the “idea” of the artists realizable; but from the start, artists have always conceived the arts as proofs of inventiveness rather than as safeguards of truth; and, particularly for modern art, what is important above all is not that the effects of the work conform to some sort of an “idea”, to some sort of a “reality” (of the soul, of feeling, of man, of social structures, of political conflicts): what is important is the tenor of the works’ capacity for new effects.

This novelty can be misunderstood, assimilated to the tradition of the new introduced by the grand industry of consumption, and reduced to the mercantilism of “innovations”. But novelty is still something else and is quite serious; it says: there is no nature, no history, no good god, there is no received, given, revealed, discovered meaning; there are (so to speak) chromatic, sonorous, linguistic energies that obey constants of order only by exception, and, as with every bit of matter, it is man’s responsibility to play with these energies to make them into perspectives, sets of relations. The object of these instances of play is neither to attain the true, to obtain happiness, nor to demonstrate his mastery, but to take part in the simple capacity of putting in perspective, even on a minuscule scale. (What is written here for its part is nothing but a brief putting in perspective.)

This is how the decadence of the true can be deepened in science. It has a choice to make concerning the place to give efficiency and control: either the occasion of an increased rationalization and totalitarianism, or the means to multiply inventive realities. It is to be expected that science gets around itself cunningly.

-

Decadence of the idea of labor

Another question: what is in decadence? Nietzsche says that values are in decadence. Some people think, especially during these times of unemployment, that it is capitalism, that capitalism is in crisis, and that crisis always signifies (whether in the short or long term) an impossibility of functioning, a blockage in the course of a process (we shall return to this notion soon).

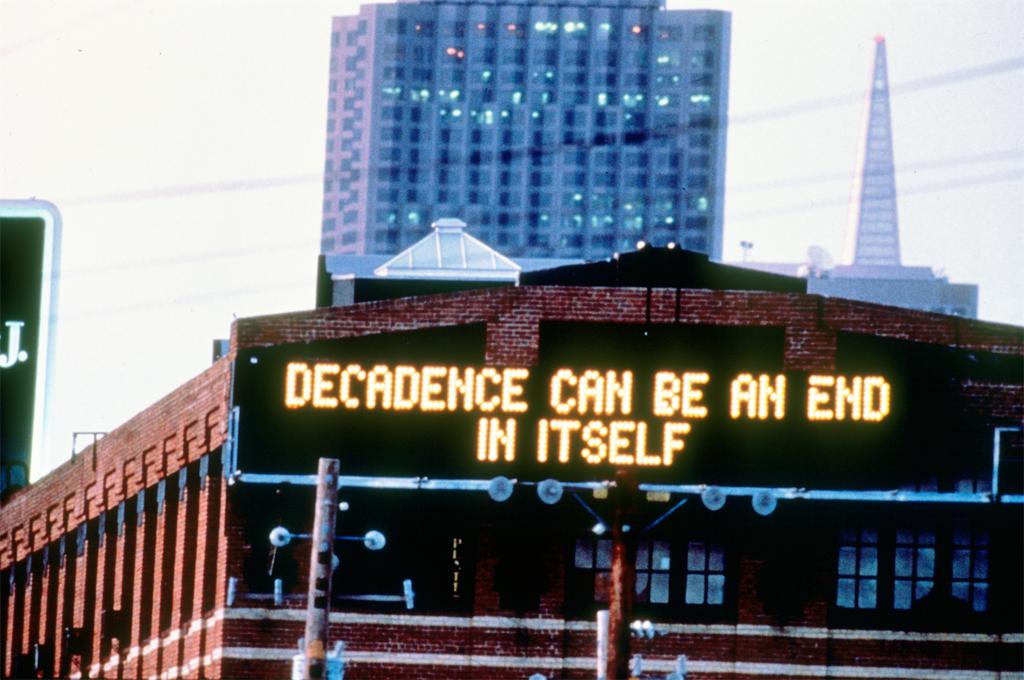

But we need to note something beforehand: capital is not aware of a crisis, it is not itself in decadence, but its functioning supposes and involves decadence [la décadence], or, if you will, crisis [la crise]. Better yet, crisis is a condition of its possibility of functioning.

Capital is crisis because, as Marx said, it must destroy precapitalist institutions, values, and norms, and it must regulate the “production” and “circulation” of goods, men, women, children born and to be born, words… But it is still crisis because it must incessantly proceed to the destruction of its own creation. Here, once again, we encounter this movement on the spot we brought up a moment ago. This is a sort of incessant crushing movement, a movement of destruction/construction. Crisis, just as much as capital, is permanent. And if, borrowing from Nietzsche, one intends to give it the connotation of a decadence, this is because the functioning of capital in effect requires that it equally disaggregate and elaborate familial and social institutions, human communities, etc.

Nietzsche himself does not describe this situation as that of capital. He speaks of the decadence of values and of culture, but he does not attribute it. I believe that he has a “reason” for this: decadence is a perspective that is an indispensable complement to another perspective, that of “Platonism”. To present decadence in terms of capital shows that capitalism is a new but displaced stance of Platonism, a Platonism of economic and social life; this is not to explain decadence through capital but only to extend the idea of “perspective”, to relativize the dispositif of “modernity”, and also to refuse the therapeutic attitude, since the latter is part of decadence.

Now with the case of labor. For Marx, the value of labor, the importance granted to it, both in society as well as in the life of individuals, is put back into question: what must be abolished is the exploitation and alienation that productive activity undergoes. However, particularly in the West, it is today more probable than ever that the value granted to labor is on the decline.[note] See in particular the investigation of Jean Rousselet, l’Allergie au travail [The Allergy to Work], Seuil, 1974, and J.-P. Barou, Gilda je t’aime, à bas le travail! [I Love You Gilda, Down with Work!], France Sauvage, 1975.[/note] In France, a recent investigation reveals that in nearly 50/100 youths from amongst all socioprofessional categories, labor is not recognized as having any other goal than to ensure survival. Labor is denied all ethical value (it is good to work) and all value of the individual ideal (it is in work that I realize myself, thus coming nearer to the Freudian ego ideal). In other words, the idea of labor has lost a part of its motivational power: yet the latter was not only an important piece in the functioning of the great capitalist machine, it was also a resource of socialist critique, insofar as it conveyed the distaste of the aristocratic professions for the industrial conditions of labor.

The phenomenon is interesting because it is visibly inscribed in the movement of decadence: the system destroys a value that seems indispensable to it.

But here still, it is necessary to ward off the trap that, for politics on the left, the habit of thinking in terms of underlying processes tends toward, i.e. in terms of Augustinian or Hegelian history leading to an end. It would be useless to build a politics modeled on such a conception of history, to build it on the perspective of the ruin of the value of labor. The decadence of this idea is not its simple decline, and it in no way causes a catastrophe. The decline is constantly reprised, inverted, and neutralized in many different ways. First, socioeconomically: the part of total capital that is invested in labor-capacity[note][Here, I am following the translation of force de travail (Arbeitskraft) as labor-capacity, which is also translated by other translators of Marx as labor-power — TN].[/note] diminishes to the benefit of the part immobilized in the means of production; at the limit, there should be a production without workers; in any case, the crisis of labor would then lose its importance. But this deepening of the organic composition of capital is in turn subject to caution; one must distinguish the quantity of wages and the amount of wages, one must count the indirect wages that enter into the circulation of capital, one must introduce employment multipliers for each technical or technological “improvement”, there is the immigration of labor-capacity coming from the Third World, etc. All of this tends to maintain a certain rate of employment and thereby the actuality of a “crisis” of the idea of labor.

Above all, the important point is that capitalism does not need labor to be valued (no more than it needs truth to be valued in the order of scientific discourse), since it merely suffices for labor to exist. It is in this sense even better for capitalism: the attachments of the qualified worker to his professional habits are misunderstandings that block a free circulation of labor-capacity. The pulsional[note][The word pulsionnel in French is the adjectival rendering of Freud’s Trieb (drive, rendered in French as pulsion) and is misleadingly translated by Strachey as “instinct”. See Iain Hamilton Grant’s translation of Lyotard’s Libidinal Economy, specifically his explanations in the introductory glossary to that work — TN][/note] dispositif of investments into products, tools, and manners of operating gives way to completely different investments. It is premature to claim to define these investments in libidinal terms, for in reality there must be quite a large number of them. It is nevertheless very important to show that under what is generically called wage labor various modifications are produced in — and produce — the placement of affects onto tasks. “Alienation” is not just a term that belongs to the pedagogical problematic (that of the masters) but is a tenuous word that does not allow these modifications to be distinguished and navigated but on the contrary obscures them.

These questions of names overshadow concrete attitudes. All the discourses and actions of protest or politics that remain content with denouncing wages (exploitation) or labor conditions (alienation) in order to improve them are so many refusals to resonate with and navigate the modifications of libidinal investment we are referring to, and thus they are merely various repressive blockages. Syndicalists and politicians channel the wealth of decadence-on-the-spot from the idea of labor into the lexicon, syntax, and rhetoric of the masters’ discourse, into the masters’ space-time. It should not be said that this is because they are evil or bad, etc., but that this is in their interest; and it should no longer be said that none of this decadence lends itself to being translated into widespread protests and programs. With the circumstantial complicity of the interested parties themselves, the crushing that workers’ organizations make the libidinal displacements of labor undergo stems from the fact that the apparatuses represent their leaders and incarnate the subject they are supposed to constitute, either in a unitary space and time or on the so-called scene of history. The displacements of libidinal investment onto labor occur in spaces and times and obey logics that have nothing to do with the philosophy of history, even though they are not embedded anywhere else. They indeed take place there, but the signs that they constitute (protest movements, declarations, demonstrations) are not the tensions that they are.

If it would be necessary to clarify these mysterious tensions or drifts for labor, we could seize upon the occasion of the present “crisis” associated with the increase in the price of energy in Western Europe. The reduction of purchasing power (not to mention unemployment) that must result from this is well known. In the protest-perspective, the alternative is simple: either workers are crushed by their pauperization, and the fear of losing what little remains for them annihilates their combativeness; or, exasperated, “having nothing left to lose”, they engage in long-term struggles. These are the two statements that make possible and can anticipate militant language. And what else can the “masses” say, if they must speak a language that can be quickly translated by their leaders into dialogues with the bosses and into the decisions of actions, beyond: Yes, let’s go/no, let’s not?[note][The phrase here on y va can mean “let’s go”, “want to go”, and “here we go”, depending on the emphasis of its performance as a question, command, or invitation — TN].[/note]

However, as these lines are currently being written, it seems as though nothing of the sort is taking place: neither great fear, nor great revolt. Not that nothing is happening, but that what is happening is not currently being said in this language. This is not only true of the visible movements, whose singularities, if one is not on the spot, are difficult to describe. It is also probably the case for situations or facts that are deemed adjacent and are indeed connected if one sticks to the authoritative language of militants, albeit within the confines of the spatiotemporal and logical dimensions of an “experience” that this language ignores.

To come back to the case of labor, black labor would be one of these notable displacements. In the current crisis, a doubly important function could be supposed for it. First, it is likely that it allows for many of the employed and unemployed to illegally maintain their purchasing power; second, its singular epistemological property deserves some attention: just because it escapes from economic and sociological enquiry due to its position doesn’t mean that its scope cannot be appreciated and that the totalitarian desire for “clairvoyance” then encounters a hermetic opacity; but if its scope is supposed as non-negligible, it must be acknowledged that many goods and services are exchanged without passing through the intermediary of the masters’ control, whatever the bosses, local or national administrations, or syndical agencies may be. Since this involves jobs of payment, upkeep, or fabrication to order, it is most likely here that one would not find the features of a series of industrial labor: this is a different pulsional investment. Similarly, the relations in this sort of work would need to be described carefully: the controls of the employer, of the syndicate, of the administrations are short-circuited, the client is often known, one arranges with him directly, etc. It is certainly necessary to be wary about building on these discrepancies a sort of utopia of good or true labor, which would be the underground.

Thus, within the body of capital, there is another form of socioeconomic life, another “kingdom”, one that is acentric and is constituted by a multitude of singular or anarchic exchanges, foreign to the “rationality” of production. And it cannot be said that this way of living is a challenge or a critique of capitalism (it is not even certain that it is related to the decadence of the idea of labor). But it reveals this paradox that, even in a society mainly centered on production and consumption, working can become a minoritarian activity in the sense that it is unrelated to the Center, neither evoked nor controlled by it.

This independence is vast; if it is true that black labor is a manner of getting around the decrease in the standard of living, then it is a stratagem that does not imply any resentment; the “crisis” is experienced unabated and without revolt, without credulity toward catastrophism. These features appear most strikingly in Italy no doubt, in everyday life, in la petite vie: again and again, one encounters there many situations that are far from being exclusively agreeable (or disagreeable), that are all formed by initiatives that are independent from or unconcerned with the central power. A sort of “civil society”, one that is not Hegelian but is quite flexible and active, never stops eluding the authorities of the masters.

The lie as perspective

Now for another, less sociological reflection on “crisis”. The very idea of crisis, as we said, inscribes the object in a dialectical perspective. The latter sketches out the image of a history, a sort of body bathing in a homogeneous temporality where it will attain the limit of its organization, exceed its conditions of possibility, and disintegrate into something else. Particularly in Capital, Marx suggests that crisis is the contradictory moment internal to capital that leads the latter to its end. This amounts to situating the social body in a negative temporality, in a time that is the concept itself insofar as it is contradictory. The question is what halts the choice of the type of temporality. Can a practice be situated in another temporality than that of the concept?

According to Nietzsche, decadence introduces three categories: the true, unity, and finality. Decadence of the true = decadence of a certain logic, of a certain type of rationality; decadence of unity = decadence of a unitary space, of a sociocultural space endowed with a central discourse; decadence of finality = decadence of an eschatological, oriented, finalized temporality.

If these multiple aspects are transcribed in terms of capital, it becomes clear that each of them designates logical, topical, and chronic operators that define new “political” practices.

Back to the decadence of the True: capital is this alleged organism that is nevertheless incapable of providing the discourse to found its own truth. It does not resort to religious, metaphysical discourse, which is capable of accounting for its existence and lending it authority. Not the least bit of this is why I’m here, or this is why I have or I am power. Not only is our society deprived of foundation, but it also intensely makes the very idea of a foundation, of a final authority, decline. Instead, capital takes initiative; this is an inventive perspective, in a sense, because it completely reverses the question of meaning: I laugh, it says, at founding meaning, i.e. at receiving it from elsewhere; on the contrary, I propose axiomatics that are decisions about what has meaning, that are choices of meaning. The coherence of the system rests on meta-statements that must be able to be grouped into a set of axioms: everything must be in agreement with these axioms, failing which there is a violation of “rationality”. All analytic philosophy and modern logic work in this vein. What has Piero Sraffa done, if not write the axiomatics of a capitalism regulated in a self-replacing state?[note][The italicized words are English in the original text — TN].[/note]

However, a path is indicated here that is not one of theoretical, epistemological, or political critique, but where a completely different pseudo-theoretical and pseudo-political perspective can be “taken”. This formalism, which gives rise to (for example, economic) axiomatics, maintains a certain status of truth. The latter is quite different from what it is in a metaphysics or in the theology of a revealed religion; but it must exist, without which it becomes impossible to assign any statement a determined truth-value. Statements that declare the truth or falsity of a set of statements must not belong to the class of the latter. In other words, the discourse that decides on the true must not be included in the (mathematical, etc. but also economic, political, etc.) discourse whose conditions of truth, the axioms, it establishes.

To speak concretely, the baker’s statement “this Parisian bread is worth x cents” or the boss’s statement “your hourly wage is worth x francs” (type 1) must not belong to the same class as the statement that says, “these values are correct” (type 2). What does this latter proposition state? The authority of a power, government, chamber, or union, which is itself the expression of a sovereign, the “legislator”, is supposed to be, for example, the “people”. If for the time being one neglects the question of representativity, how is this authority recognized in terms of truth-value? Precisely due to the simple property that its statements establish the value (true/false, good/bad, etc.) of other statements, those of the boss and the baker, and because they therefore do not belong to the same class as the latter.

Thus, to dissociate the statements of type 1 (whose references are some sort of “object”: bread, hourly wage — commodities in our example, although there are many others: children in school, number of sexual partners, parental responsibility…) from the statements of type 2, whose references are totalities of statements of type 1 — “we declare true that Parisian bread is worth 150 cents”, i.e. for whichever propositional variable x (this bread here, that bread there, individual-breads), the statement f(x) = y, which is read as “for x, the price in francs is 1.50”, is always true.

(Here, we should note that Marx maintains this position of truth. The text of Capital indeed implies that there is a statement or group of statements of type 2 which assert the truth-value of all the statements of type 1, i.e. the equations regulating capitalist exchanges: money/commodities. Marx’s meta-discourse declares that it is not true that all exchanges take place at equal value; he at least detects an inequality in them, which is that of the inequality of labor power with the commodity, and this is how he is critical. But Marx himself establishes a statement of type 2: “I declare true that every value of a commodity consists in the total amount of time of the average social labor necessary for its production”; this equation is the meta-operator for all the others; it is not a part of them.)

However, this dissociation of statements from meta-statements merely requires a decision. One decides before everything else to safeguard the possibility of the true. This is what Bertrand Russell says unambiguously when he endeavors to refute the liar’s paradox.[note]Cf. chapter VII of Bertrand Russell, My Philosophical Development, London: George Allen & Unwin (1959).[/note] Cicero relates this paradox in the following way: If you are saying that you are lying and you tell the truth, then you are lying.[note]Cicero, Academica, II.[/note] This statement thrusts us into undecidability: if you are lying when you say that you are lying, well, then you are telling the truth; but if you are telling the truth although you say that you are lying, then you are lying… Russell wants to stop the perplexity by declaring that “you are lying” is a statement of type 1 and “you are saying (true or false) that…” is a statement of type 2. The paralogism consists in including the second statement in the set of the first.

The goal toward which the labor of the logician strives is to safeguard metalanguage (which is understood as language that establishes the truth-values for a set of statements). This is also the goal of the Centre, except that the latter in turn intends to authorize the type 2 status of its statements by deriving it from an authority of superior status, for example the opinion of the majority (or something similar). By all means, this is not less paradoxical than the liar’s paradox, since this majoritarian opinion consists of type 1 statements.[note]It will be given afterwards elsewhere.[/note]

Even without insisting on this circulus, this little circle, it remains that in the wake of Russell’s reflection, a decision must be taken to disjoin statements 1 and 2 if we want the truth-value of whichever statement to be decidable. The liar’s paradox indeed mocks one’s ability or inability to say of a statement that it is true or false; furthermore, it constitutes a little dispositif such that this decision cannot be taken and thus where no authority can be established or halted that resorts to metalanguage. It thus inspires a completely different “logic” wherein there would be no metalanguage, not because it would be forever hidden (as in a certain (Judaic) religion or in a certain (Lacanian) version of the unconscious), but because falsehood and veracity are indiscernible. Any statement with metalinguistic pretention is potentially capable of belonging to the set of statements that constitute its reference. But no one knows when… On occasion, the class of all classes is part of the latter.

If one now directly and abruptly transposes this latter proposition into the socioeconomic domain, it implies that no social “class” has authority or calling to make use of metalanguage, or it implies that every “class” does: no one knows when the master is lying and when he tells the truth. And social class must be understood as every set of individuals defined by a bundle of distinctive traits: housewives, proprietors of capital, Bretons, left-handers, vegetarians, college graduates… Thus, one can see how the logic revealed by the decadence of the true here encounters the politics of minorities about which we spoke earlier: politics without master, logic without metalanguage. But enough of this for the moment.

Minorities as perspective

On the decadence of unity, the second trait revealed by Nietzsche, which we are here taking in its political sense — it has been said that capitalism invented the nation. It certainly is a question of a historical shortcut; nevertheless, it can be acknowledged that the bourgeoisie have if not produced then at least imposed (under the name of the nation) a sort of meta-set of various populations whose unity was connoted economically, politically, and sometimes religiously and culturally. We are in the last quarter of the 20th century, and it seems that an apparently inverse movement is being put in motion. This is a decadence-movement of national unity that tends to bring forth multiplicities, and these multiplicities are far from merely being what they were before the formation of national unities. This movement can seem like the adversary of capitalism, but it belongs to the decadence of values, which is contemporaneous with it. Nietzsche says: why have we become incredulous and mistrustful? Because we have taught veracity and because we have turned the requirement back against the speech that would be taken for veracity itself, i.e. revealed speech. It can also be said: why are national minorities rising up in modern countries? Because we have taught the minority that they were taken as placeholders of the nation. Nations are born in the breakup of the space of Empire; but this breakup has formed many empires; for the provinces of today, the national capital is what Rome was for the provinces of yesteryear. On the scale of mainland France, the royal masters or the republicans of Paris have not been and are not less imperialist in regard to the provinces than Rome was to its own or its allies. The language maintained by Paris is suspicious, detested. Centralism is put into question, along with the sociopolitical (and economic) space that is proper to it, including its Euclidean traits: the isomorphism of all its regions, the neutrality of all its directions, and the commutability of all its figures according to the laws of transformation were already present in the Greek ideal and in the Jacobin idea of citizenship.

What is outlined is a group (to be defined) of heterogeneous spaces, a great patchwork of fully minoritarian singularities; broken is the mirror in which they are supposed to recognize their unity by means of the national image — decadence of the mise en scène of the spectacular production that was the political. Europe takes it down a notch in the definition of elementary political groups: whereas the masters tried to unify it from on high, the little people reconstructed its apportionment from below.

This is of the utmost importance. Not that it is fitting to attain from this the promise of a happiness, of an equality… For example, there is already something like this in American sociocultural space, yet the coexistence of a large number of minorities is not quite Edenic there. In the wake of the decadence of unity, a problem is posed that was already posed by politicians (by the communists in particular) but is now posed in the most secret and yet most prominent affects of peoples: either the upkeep of the Centre, of some phraseology that is political (union of republics, of States, federation, republic, empire…) or socioeconomic (liberalism, socialism) and with which the masters’ function is equipped; or the breakup into minorities, whose responsibilities are to incessantly establish and reestablish modūs vivendi among them. The decadence of the Centre goes hand in hand with the decline of the idea of Empire. In this context, there is more to find on the side of the thinkers of multiplicities (like Thucydides and Machiavelli) than on the sides of the centralists of every allegiance.

Let’s add two more observations on this point. First, the movement of breakup involves not just nations but also societies; the appearance of new elementary groups that were not recorded on the Official Register: women, homosexuals, divorcés, prostitutes, expropriés[note][This term refers to those who have been subjected to the compulsory purchase of property due to eminent domain — TN].[/note], immigrants…; the multiplication of categories goes hand in hand with the weighing-down and complication of central bureaucracy, but also the tendency to regulate its affairs itself without passing through the authorized intermediary of the Centre or by short-circuiting it cynically (as in the taking of hostages).

And secondly, in relation to this process of multiplication, the existing political organizations seem completely engaged in the other direction. They fully belong to the masters’ reassuring, representative, exclusivist space. They largely contribute to the procrastination of the Centre’s decadence. The “politics” of minorities demands their decline.

Opportunity as perspective

A short note on the decadence of finality. The years 1850-1950 flourished with eschatological discourses, some on the liberal, planist, fascist, Nazi side and some on the socialist, Bolshevik, communist side. These are intense, bloody oppositions, but they are in the same field of a temporality oriented by the more or less compatible values of happiness, freedom, grandeur, security, prosperity, justice, equality. In short, the field shared by these finalisms is the one that Augustine circumscribes: The City of God contains both the theme of the accumulation of experiences — which is taken up again in a laicized form in the discourse of liberalism — and the theme of the reversal of hierarchies — which will provide their resource to revolutionary movements. Both of these themes are articulated in a teleology. The great opposition of continuous time and discontinuous time, which sparked quite a few intense discussions in the German socialist movement of the 1880s and afterwards or gave rise to Lenin’s break with the Bolshevik direction in April 1917, stems from the same approach to temporality.

However, all of this remains lively in liberal discourse as well as in discourse on the left; all of this remains capable of gathering together the accumulated forces of malaise and discontent in the little people and of the will to more power in the bigwigs. It shouldn’t be said that all of this is finished or will finish, which would be a new eschatology. But the decadence of ends penetrates this liveliness itself, which consists in the reduction of their capacity to “put in perspective”. The finalism on the left, which is the only one that interests us (for right or wrong), can indeed speak out and now gain a non-negligible number of votes, such that no one lives according to its values and such that no one is in a state of sacrificing himself — as it is said according to Jesus in Matthew XIX, 16-30 — and his real-life acquisitions, even in a particular “grand occasion”…with the exception of the politicians. The decadence of the idea of revolution can be compared (this isn’t saying anything new) to that of the idea of the Last Judgment in the beginnings of Christianity: the managers of the ecclesiastical empire replace the ever-absent kingdom of Jesus. Alas, they are neither traitors nor imposters, they are instead exemplary! Their force is due to the fact that they maintain a perspective that saves Western humanity from falling into nihilism. The Church (= the Party), or nothing (= nothingness, interminable evil).

What politicians (privately) disparage as the apathy of the masses, as the decrease in combativeness, as alienation, is something completely different. It is an intense discordance, even if it is sometimes imperceptible, between the so-called political perspective and another barely defined perspective; and this discordance does not pass between the leaders and the people on the ground, but it suffuses everyone. It well and truly bears on temporality. The political voice says, await, hope, endeavor, prepare, organize; and the other voice says, seize the proper moment, the future is, potentially and not necessarily, in the moment and not tomorrow, no voluntarism, do what presents itself as to be done, listen to what desire asks and do it. Thus, no eschatological historicization, but oppositely, no more ethics of the fulfillment of desires or theology of jouissance (which are the simple reversals of classical asceticism and in the same field). Opportunity, what the Tragedians and Gorgias called kairos.

Nothing is more realist than this other perspective, contrary to what is said to disparage it. Many struggles that arose in endeavors or elsewhere — for several years, perhaps since time immemorial — have resorted to this perspective, alongside others. It is in the eschatological perspective that one claims to oppose such an initiative — which was previously taken as imaginary, unrealistic, irresponsible — to an alleged final reality in the last analysis. It therefore matters little that politicians launch these invectives. After a century of their practice, the present state of things provides the measure of their realism.

An effectiveness without third-party

Back to the Red Army Faction . What is the nature of the expected effectiveness of its actions? The problem does not lack an analogy with the one posed by scientific efficiency. The objection raised against the new perspective[note]We are referring only to what is formulated by thinkers open or inclined to the aforementioned perspective: Pierre Gaudibert, l’Ordre moral, Grasset, 1973, pp. 141-152; Mikel Dufrenne, Art et politique, U.G.E., 10/18, 1974, chapter VII.[/note] is to neglect effectiveness. You will not unsettle the system if you do not coordinate your actions, if you do not explain the scope of your actions. Without this, these are merely tiny libidinal self-indulgences within little unproductive minorities that will not convey the slightest (we won’t even say attack but) offense against the system.

Let’s not discuss this at the moment but instead observe the following: that in a movement as extreme as the RAF, the value of effectiveness is in full decadence, and that the latter doesn’t quite consist (as our objectors seem to believe) in negligence for effects, but in a sort of double movement: the attention on effects is split along two perspectives. There are two sorts of effects which are sometimes not distinguished, and so here as well we will have to choose.

Dufrenne cites certain passages of Marcuse[note]Herbert Marcuse, Counterrevolution and Revolt, Boston: Beacon Press, 1972.[/note], of which he disapproves without ever disavowing, where effectiveness is overtly subordinated to pedagogy, thus conforming with the tradition of old. However, in the dossier of the Baader-Meinhof trial, there are traces of this classical attitude. To a question asked by one of Der Spiegel‘s journalists, “Don’t you see that no one is taking to the streets for you? Don’t you see that when you started setting off bombs, no one is speaking out on your behalf?”[note] Baader-Meinhof, op. Cit., p. 241.[/note], the member of the RAF responds by citing polls from 1972 and 1973 that claim to show support for the group with the German public and thus tend to prove that if the group has not convinced, it has at least succeeded in gaining the sympathy of an important part of the population: an indispensable moment in the pedagogical process.

Or, in the leaflet of 2 February 1975 ordering prisoners to stop their hunger strike, it reads, “The class struggles are not sufficiently developed due to the corruption of the organizations of the proletariat class and a weak revolutionary left […]. The possibilities of the lawful left […] have not been sufficiently developed […]. We declare that the strike has accomplished just about what could be done here to explain, mobilize, and organize anti-imperialist politics, its escalation has not been perceived as a new quality of struggle.”[note] Ibid., pp. 213-214.[/note]

The effectiveness required here is that of pedagogy: to make the principle of rationality, the Platonic logikon, rise up in the soul of children, the masses. Thus, there are three poles in this strategic field: we, the RAF; them, the imperialist apparatus; you, the students, the masses. We are effective each time you understand. But who will judge whether you understand? This will be when you will come to agree with us, i.e. if you speak according to our language and act according to our ethics. Thus, we shall judge, just like Socrates judges the moment when Meno is rational and when he is not. (In any case, we specify that our description does not at all imply that it would be necessary to continue the hunger strike at all costs…).

But a totally different effectiveness is sought and sometimes obtained by the same group. For example: in Heidelberg, when it destroys the American army’s computer, which, among other things, programmed the bombings in North Vietnam, it doesn’t say: the masses will understand, but: this is potentially an accomplishment against the imperialist adversary, one that is not merely a military accomplishment but a moral one, too.[note] Baader-Meinhof, p. 239.[/note] This is everything. Here, this is a strategy without third-party (moreover, a false third-party, since one of the parties, Socrates, is also the judge): just the RAF and the American army. The anticipated effect is not the awakening of the logikon of the masses but the disorganization (albeit provisional) of the enemy. There’s no demonstration. And this is indeed what the group writes: “We conclude that the revolutionary subject is everyone who is freed from these constraints of the system and refuses participation in the crimes of the system. Those who find their political identity in the struggles of the liberation of the peoples of the Third World, those who refuse, who no longer toe the line, are all a revolutionary subject, a comrade”.[note]Waging the anti-imperialist struggle, constructing the Red Army [Mener la lutte anti-imperialiste, construire l’armée rouge], leaflet of the RAF, 1972, cited by Viktor Kleinkrieg (great name!), op. cit., p. 33 (passage emphasized in the text). [Kleinkrieg in German literally means “little war” — TN].[/note]

This is how the disappearance of the third-party, of the child as potential reasonable subject, of the proletariat as potential revolutionary subject, is described. And an immediate implication of this disappearance is found in the responses to Der Spiegel, in the statement of principle a propos of the penitentiary regime: “Every political prisoner who understands his situation politically and who organizes the solidarity and struggle of prisoners is a political prisoner, whatever the reason for their imprisonment may be”.[note] Op. cit., p. 219.[/note] This is a perspective that emerges in the old words. Let’s imagine that such was the course of the German (and other) communists in the Nazi camps, instead of that of saving the apparatus at all costs, the one David Rousset describes…

Thus, what effectiveness? We are not defending the military strategy of the RAF here; we instead would think that the extremism of its actions, in its very hopelessness and by inversion, remains subordinate to the classical model of educative political action. And this is no doubt why in matters of effectiveness the procrastination of decadence appears in this apparently borderline case.

The elimination of the educable third-party belongs to the new perspective, along with the elimination of finality, truth, and unity; and its upkeep belongs to the old perspective in which we are also immersed. In the first case, there is no body to be organized and reorganized, but harassments. And here it would be necessary to show 1) that there are other types of harassments than bombings and 2) in what harassment consists. It could be shown that there is also something like a retaliation, the ruse or machination by which the little people, the “weak”, become momentarily stronger than the strongest. To make a weapon out of illness, said the Socialist Collective of the Heidelberg patients. And the Convention against the Torture of political prisoners in the German Federal Republic: “Become aware of this material force that is weakness transformed into force”.

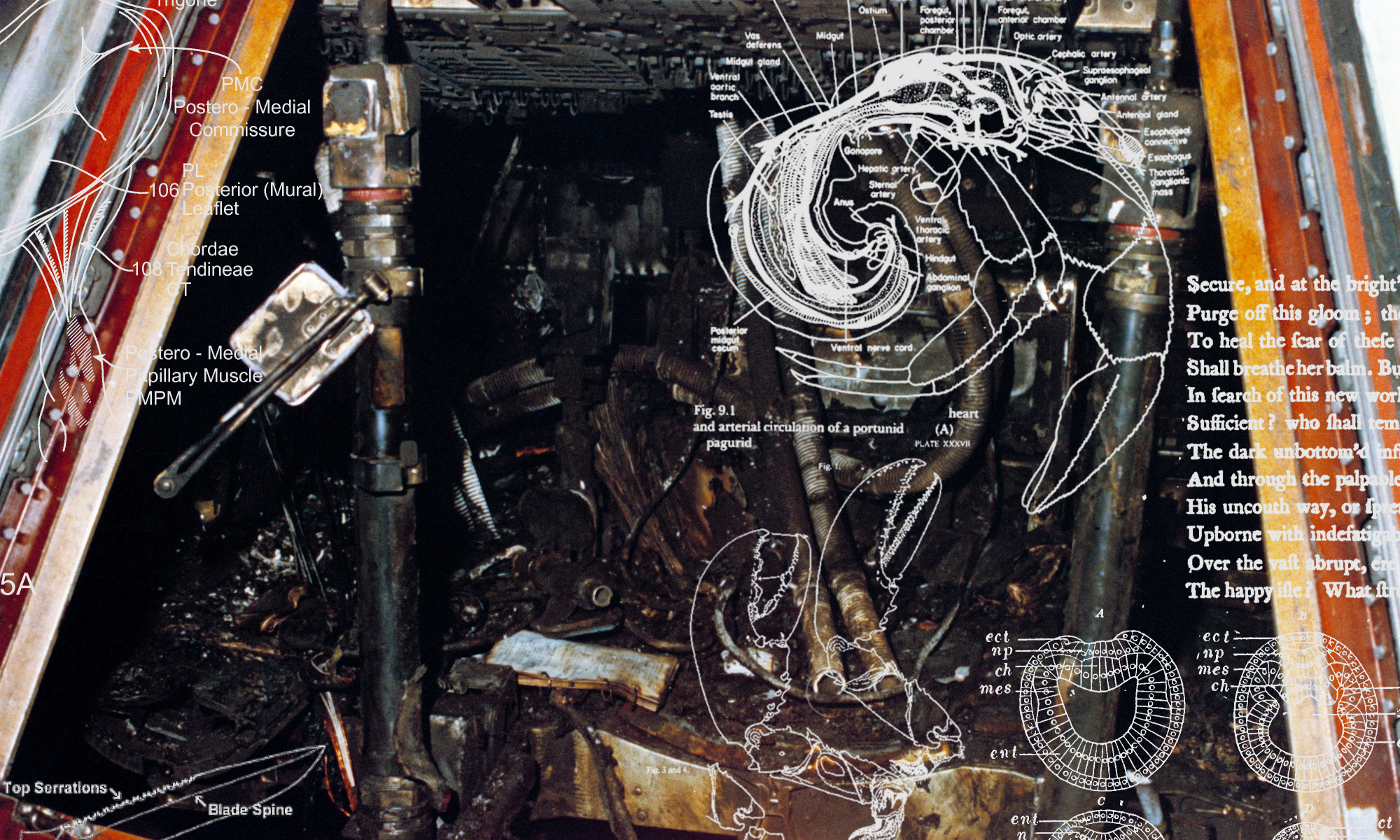

These retaliations belong to a logic that is a logic of first-generation sophists and rhetoricians, not of the logician, to a time of opportunities, not of the clock of world history, to a space of minorities, without center. ![]()

This essay was translated for Vast Abrupt by Taylor Adkins. Other translations by Adkins can be found at Speculative Heresy and Fractal Ontology. Adkins is also the host, with Joseph Weissman, of the philosophy podcast Theory Talk. You can support Theory Talk and their continued good work through Patreon.

One Reply to “A Brief Putting in Perspective of Decadence and of Several Minoritarian Battles To Be Waged”