by Laurence Kent

Thought is primarily trespass and violence, the enemy, and nothing presupposes philosophy: everything begins with misosophy.

—Gilles Deleuze[note]Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, trans. Paul Patton (1968; New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), 139.[/note]

A philosophy of horror inevitably reaches transcendental limits; it is thought itself which is born in the shadowy depths of a horrific sublime. Nick Land screeches in the void that “horror first encounters ‘that’ which philosophy eventually seeks to know”, and we will trace this pre-philosophical trauma of thinking in the abstract spaces of German Expressionist cinema.[note]Nick Land, “Abstract Horror (Part 1),” Outside In (blog), August 21, 2013, http://www.xenosystems.net/abstract-horror-part-1/[/note]

The Discordant Harmony of the Sublime

For Kant, the sublime is a form of aesthetic judgement that arises when the faculty of imagination is stretched beyond its limits. This violence done to the imagination in the face of a formless presence of ungraspable immensity or power creates a negative pleasure. In the wake of imagination’s inadequacy, the Ideas of reason take over, proving that “the mind has a power surpassing any standard of sense”.[note]Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgment, trans. Mary J. Gregor and Werner S. Pluhar (1790; Indianapolis, Ind: Hackett Publishing, 1987), 106.[/note] Kant divides the sublime into mathematical and dynamic variants, depending on whether the encounter is with an immense magnitude, stretching our “cognitive power”, or if an unimaginable might is presented, stretching our “power of desire”.[note]Ibid., 101.[/note]

However, the concept of the sublime is not merely an aesthetic category in Gilles Deleuze’s reading of Kant, and in fact provides support for the transcendental faculties. The sublime marks an important step in the communication between faculties; it confronts us with a direct subjective relationship between imagination and reason. What makes this relationship important is that, unlike the free play of imagination and understanding that takes place in the judgement of the beautiful, the sublime brings the faculties into a discordant harmony. The sublime points to the genesis of the faculties’ accord in discord. The third critique grounds the first two critiques, but at the same time undermines the presence of a stable ground or natural harmony between our thinking faculties. The sublime indexes the groundless ground of apperception.

We thus find a violence at the birth of thought, a traumatic encounter with an outside that cannot be assimilated — something that can only ever be problematic to thinking; as Land writes, “the sublime is only touched upon as pathological disaster”.[note]Nick Land, “Delighted to Death,” in Fanged Noumena: Collected Writings 1987-2007, ed. Robin Mackay and Ray Brassier (Falmouth, UK: Urbanomic, 2011), 135.[/note] Something is sensed which is imperceptible, something is thought which must remain unthought. This is the transcendental exercise of the faculties: when a faculty takes its own limit as its object – not empirical or part of the given, but the genesis of the empirical, that by which the given is given.

Gothic Geometry

To flesh out some of these claims, we turn to Deleuze’s analysis of German Expressionism in Cinema 1, and especially his take on Robert Wiene’s 1921 film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Deleuze’s analysis of German cinema lies in the shadows of art historian Wilhelm Worringer. Art, for Worringer, exists because it fulfils certain psychic needs, and this will to form of artistic creation shifts with historical epoch depending on the relationship between humans and their environment. Worringer theorizes two urges that dominate the history of art: empathy and abstraction. The psychic condition that gives rise to artworks displaying the urge to empathy is “a happy pantheistic relationship of confidence between man and the phenomena of the external world”; empathetic art features naturalistic and organic aspects that allow the perceiver to enjoy their inner feeling of vitality.[note]Wilhelm Worringer, Abstraction and Empathy: A Contribution to the Psychology of Style, trans. Michael Bullock (1908; Mansfield Centre, Conn.: Martino Fine Books, 2014), 15.[/note] Abstract art, on the other hand, is created to fulfil a psychic need arising from “a great inner unrest inspired in man by the phenomena of the outside world”.[note]Ibid., 15.[/note] Abstraction soothes these psychological stresses through an encounter with a geometrical absolute where in the contemplation of abstract regularity the perceiver is delivered from tension, finding happiness in the presence of the “ultimate morphological law”.[note]Ibid., 36.[/note]

This culminates in a bizarre synthesis of empathy and abstraction that Worringer discerns in the Gothic. In the art and ornaments of pre-Renaissance Northern Europe, Worringer observes a rejection of the organic that does not fully align with the abstraction and regularity of earlier artistic periods. There is vitality but no trace of organic and naturalistic features, an indication of the inner disharmony and unclarity of the psychic landscapes in Northern Europe, a “restless life contained in [a] tangle of lines”.[note]Ibid., 77.[/note] This is the aesthetic basis for Expressionism, defined by Worringer as “that uncanny pathos which attaches to the animation of the inorganic”.[note]Ibid.[/note]

Worringer’s Gothic line is of utmost importance to Deleuze-Guattari in A Thousand Plateaus as they use it to underline their concept of the nomadic or abstract line, and more broadly their theory of art as abstract machine: the creation of striated and smooth spaces.[note]For a reading of Worringer’s influence on Deleuze-Guattari that completely excises empathy, see: Mark Fisher, “Flatline Constructs: Gothic Materialism and Cybernetic Theory-Fiction,” PhD Thesis, University of Warwick, 1999.[/note] For Deleuze-Guattari: “the abstract line is the affect of smooth spaces, not a feeling of anxiety that calls forth striation”.[note]Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (1980; Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 497.[/note] Smooth space is the space of pure intensities, in contrast to the transcendental illusion of striated space, which is segmented and ordered. Smooth space is an aesthetic model that explicates the way abstraction can express intensities, and opposed to any idea of abstraction as purely rectilinear geometric absolutes. Abstract lines do not represent anything, but are lines of pure expression, abstract productions that uncover the transcendental conditions of production itself.

The Dread of Space

In Cinema 1, Deleuze analyses the themes and aesthetic strategies of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari through the production of space in the film, the “striated, striped world” created through set design and lighting.[note]Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 1: The Movement-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam (1983; Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986), 50.[/note] By drawing lines of flight between Deleuze and his work with Guattari, these concerns can be understood alongside the framework of the striated/smooth demarcations of space conceptualized in A Thousand Plateaus. It is impossible to truly separate processes of striation and smoothing, and Deleuze-Guattari instead state that the two spaces exist only in mixture. However, they identify a de jure distinction between the two processes of space production. It is this abstract distinction that we will trace by first focusing on the methods of striation to be found in Dr. Caligari.

From the moment that the story flashes back to the town where the protagonist, Francis, used to live, the painted and artificial nature of the set is obvious. The jagged lines abstract from any possible reality a strange terror, the pointed houses themselves forming a pointed hill of impossible proportions. The first image of the town is clearly an abstract depiction of a setting, and the lack of depth in the image can be understood through Worringer’s conception of the “dread of space”. This kind of abstraction works by marking an attempt to escape from reality and is what Worringer terms an “emancipation from all the contingency and temporality of the world-picture”.[note]Worringer, Abstraction and Empathy, 44.[/note] However, it is clear that the affect of this crooked image is far from a respite for the spectator, and could more accurately be described a space of dread. This is where Worringer’s hybrid of abstraction and empathy is important. The abstraction present in the backdrop of Dr. Caligari displays a contradictory urge: both to abstraction but also to the embrace of a form of vitality. Allowing no distinction of form and background to arise, the crooked shapes and the broken lines are imbued with a twisted life of their own, a strange inorganic vitality that produces oppressive atmospheres and violent affects.

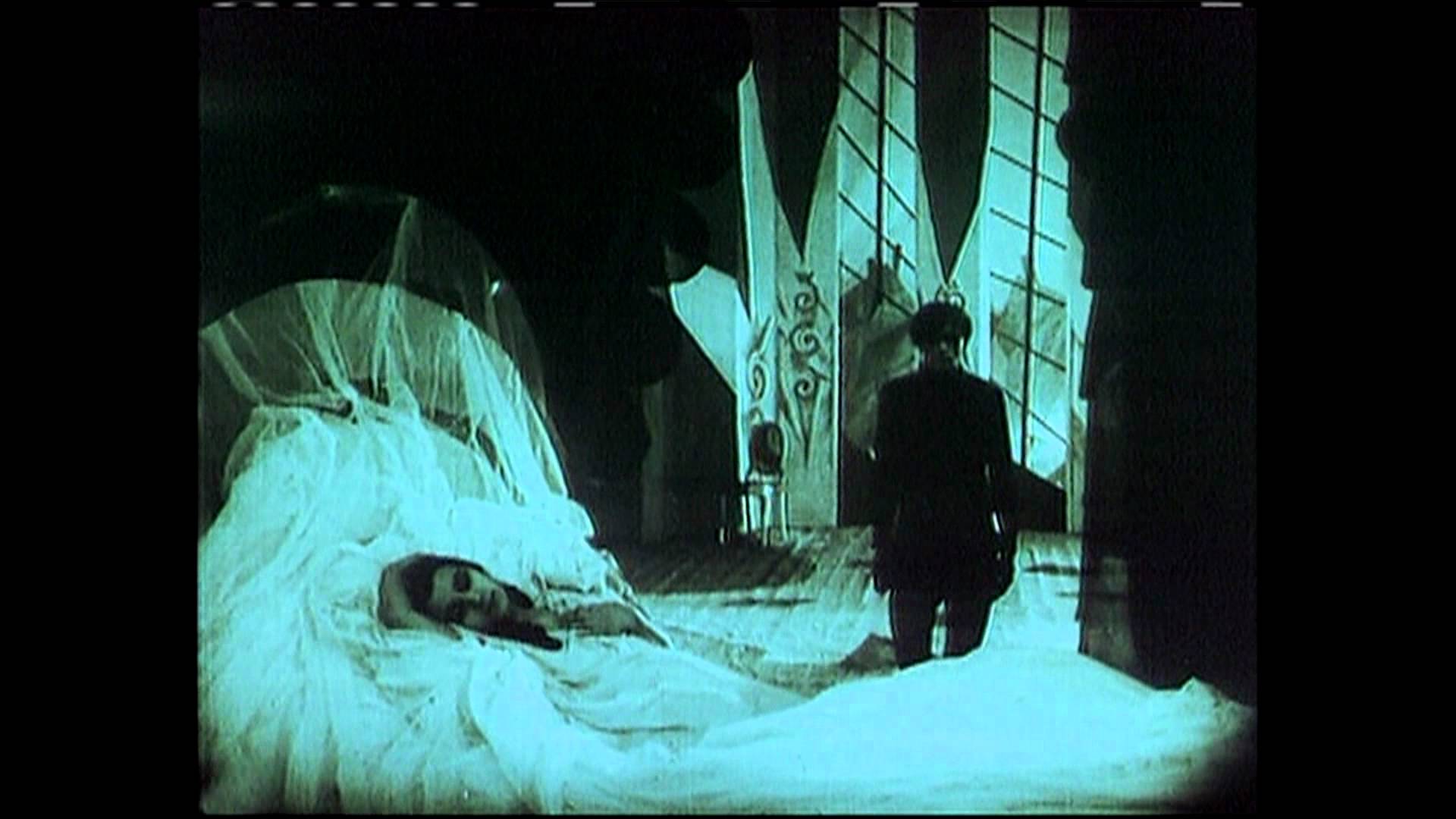

The way the characters move in Dr. Caligari can be understood as an extension of these design principles; indeed, Lotte Eisner observes that the acting is “like the broken angles of the sets” with movements that “never go beyond the limits of a given geometrical plane”.[note]Lotte H. Eisner, The Haunted Screen: Expressionism in the German Cinema and the Influence of Max Reinhardt, trans. Roger Greaves (1969; Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 25.[/note] This is thus a different kind of stratification of space, where the lines from set to character leave no separation of set and figure intact. A scene which displays the geometries of horror in the actors’ performances is the first awakening of the somnambulist Cesare. Interestingly, the background set of the stage in Caligari’s spectacle is relatively bare, with only a few jagged lines on Cesare’s coffin displaying the expressionistic impulse. But it is these lines that become intermingled with the crooked movements of both Caligari and his captured performer. Cesare slowly emerges from his box, Caligari watching him and presenting his spectacle to the audience with his rigid arms, extended and emphasized by the use of sticks in both hands. Cesare slowly walks from his box, his eyes seemingly on us the audience, a shock of self-reflexivity as we participate in the spectacle. Caligari edges out of the way, his legs straight and pushed together, his artificially extended arms pulling limited geometric poses. This is interspersed with reaction shots of the audience, the characters Francis and Allen picked out by the lighting. Their acting is more naturalistic, a trace of the organic contrasting heavily with the inorganic vitality that finds expression in the rigid movements of the characters on stage. Caligari’s and Cesare’s acting is described by Rudolf Kurtz as achieving a “dynamic synthesis of their being”, and it is the ability they have to striate the space of the image that synthesises the terror of the set design and the tension inherent in the actors’ small deliberate movements;[note]Rudolf Kurtz, Expressionism and Film, trans. Brenda Benthien (1926; Herts, UK: Indiana University Press, 2016).[/note] each body part is separate, and the organic totality of the human is lost to unknown forces controlling the characters. Cesare is the puppet of Caligari, Caligari is being controlled by madness, and perhaps both are on the strings of delirium from Francis’ troubled mind.

The lighting in Dr. Caligari works in a similar way to the acting and set design, creating spaces full of jagged lines and confusing angles. Although making a distinction between the effect of the lighting and other aspects of the mise en scène is not truly a feature of the film itself, it is through the use of lighting that we can explicate the creation of smooth space, the space of intensities. To do so, it is important first to understand the metaphysical ramifications of intensity for Deleuze as propounded in Difference and Repetition. Deleuze posits that “intensity is the form of difference in so far as this is the reason of the sensible”.[note]Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, 222.[/note] Intensity is difference-in-itself, the production of the sensible that, being its genesis, cannot be sensed. Thus, not being actual or actualisable, the notion of intensity refers to virtual events wherein any variation produces a change in the whole. This is prior to the transcendental illusion that produces measurements of extensity where quantities can be added on to each other (say time or distance). An intensive difference cannot be divided or added up in the same way. Instead, intensity marks a difference in the quality of the whole. However, we never experience intensity as, being virtual, it is only through the actualization of intensive quantities in extension or quality that intensity is grasped. Intensive quantities thus express a smooth space, away from the striation of things in terms of extension and against the understanding of the world as multiplicities upon a stable ground, the transcendental illusion of unchanging whole to which things take positions that do not change their sense.

For Deleuze, light in German Expressionism is “a potent movement of intensity, intensive movement par excellence”.[note]Deleuze, Cinema 1, 49.[/note] Light expresses an intense contrast with shadow, wherein darkness is not the negative of light but black as intensity=0. Light is thus an intensive quantity wherein the differences between light and shadow mark a virtual struggle on the scale from the zero-point of negation, and every variation expresses and actualises these virtual events in a change in the quality of the whole of the image. In Dr. Caligari, this manifests itself in the increasing tension and terror of sequences involving the somnambulist Cesare. As Cesare sneaks through the town, making his way to Lucy to commit murder, he emerges from the shadows near the door to her house. His body retains the darkness, dressed completely in black; he sticks to the wall as he advances, his shadow indistinguishable from his figure, the virtual flip-side of his actual materiality. Cesare enters Lucy’s room through a window, and his shadow skirts the lit wall as he slowly approaches Lucy’s bed, a spread of virginal white. His movements and body are a function of light and darkness, and every movement affects the whole of the image, heightening the violent affects in this intensive battle of light.

Thus, although the world of dread created in Dr. Caligari is full of striated spaces, these spaces are always on the verge of smoothing out, expressing the intensive quantities of light to produce the movements of affect in the image. The actors intrude on the sets as forms of striation, but as they become indistinguishable from the background there is a smoothing of their organic forms — but this process is one of constant oscillation as the characters dissolve from extended figures to intensive movements and back again, different forms of striation emerging from the smooth with bizarre new impetuses. To return to the aesthetics of Worringer, just as the abstraction of the sets and characters is imbued with the strange vitality usually enacted under Worringer’s conception of empathetic art, the striated and smooth are in constant mixtures, strange hybrids. As the organic representation of a world of divisions and striations starts to crumble under the non-organic life which rumbles in the virtual lines of smooth spaces, the film affects us in a more profound sense; it, argues Deleuze, “unleashes in our soul a non-psychological life of the spirit”.[note]Ibid., 54.[/note] This is the point where horror becomes sublime.

The sublime violence done to our imagination is the destruction of the organic, it is what Deleuze calls “difference as catastrophe” that acts “under the apparent equilibrium of organic representation”.[note]Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, 35.[/note] Organicism in cinema is defined by Deleuze as a sense of the whole: “a great organic unity”.[note]Deleuze, Cinema 1, 30.[/note] However, with cinema such as German Expressionism, which instead privileges the inorganic vitality of things, this sense of the unchanging whole is lost. Not only is the organic conception of the image undone but by doing violence to the spectator’s imagination in presenting an impossible whole, an intensity that can never be contained in sensibility, this invokes a destruction of the spectator’s organic being: the inorganic life overwhelms us in a dynamic sublime. This is the violence from which thought is born. We now see how the sublime is connected with the aesthetic strategies of intensive quantities: the unity of representation as a form of common-sense — in other words, apperception under the aegis of the imagination — is shown as the transcendental illusion that it is, and our higher faculties encounter the intensive movements beneath, the smooth spaces underlining the striation of thinking is revealed, forging in us an empathetic link to non-organic forces that give vitality to abstract lines.

Misosophy

The aesthetic regime of horror becomes metaphysical as it traverses the problematic origin of the faculties. Horror is important and, indeed, enjoyable as it uncovers the discord beneath the harmony of thinking that we classify as good and common sense. This harmony is thus not pre-established, but instead produced from an original contingent trauma. The non-necessity of our common-sense opens up the possibility of a different harmony, a different image of thought. Horror may not appeal to us on the surface (it is of course horrible) but it appeals to us as a “people to come” — the pain of the present being ungrounded and the pleasure of a world of pure difference: the future ravages the now.

If philosophy can never clearly think the unthought limit of thought, we find in horror a misosophy; the discord from which knowledge flows is an original rejection of knowledge, a hatred of wisdom. This does not mean that philosophical approaches to horror are futile though, but instead entail an acceptance that alongside any philosophy or horror is, what Eugene Thacker calls, a horror of philosophy, an original trauma at the birth of thought with which we must engage in order to grapple with the arbitrary nature of our philosophies: “Thought that stumbles over itself, at the edge of an abyss”.[note]Eugene Thacker, Starry Speculative Corpse: Horror of Philosophy Vol. 2 (Winchester, UK: Zero Books, 2015), 14.[/note] Noël Carrol says that “monsters are not only physically threatening; they are cognitively threatening”,[note]Noël Carroll. The Philosophy of Horror (London: Routledge, 1990), 34.[/note] and, through the aesthetic hybrids of abstraction/empathy, smooth/striated space, extensity/intensity, something foreign to our common-sense forces us to think the possibility of thinking completely differently. Horror opens the gap in our cognitive geometry, the rupture between the transcendental illusions of apperception and a possible noumenal realm of intensive difference. Encountering this undercurrent of inorganic force bring us face to face with the contingency of thinking but there is pleasure in our ability to think absolute alterity — Deleuze writes that “we lose our fear, knowing that our spiritual ‘destination’ is truly invincible”.[note]Deleuze, Cinema 1, 53.[/note] This destination of thinking is also its origin and its limit: the endless possibility of difference, where new harmonies can sound in the spectator, born from the discordant affects of horror. And, since each new image of thought must reside in the shadows of an arbitrary transcendental, terrifying yourself becomes the experimental vector of a practice of misosophy. ![]()

[/note] Milton describes how God “as with a mantle did invest / The rising world of water dark and deep, / Won from the void and formless infinite”: he provides it with a protective skin, a form-suffusing “mantle”. As such, through wrapping the entire created universe in a “clear” liquid sack, this “crystalline ocean” becomes purposed with protecting the cosmos from the “loud misrule” of the Chaos that lies just beyond it [PL; vii.269, vii.271].[note]Chaos is, thus, analogical to the ‘energetic excess’ that Freud describes as facilitating the epithelial individuation of the originary vesicle, in his account of metapsychological abiogenesis, in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (Penguin, 2003).[/note] It is therefore a prophylaxis against an external chaoticism, and — as such — a spheroid cosmic immune system and metaphysical life support.[note]Cf. Peter Sloterdijk, Globes: Macrospherology, Volume II: Spheres (Semiotexte, 2014).[/note] A crystallic womb. Certainly, pre-Copernican cosmology is precisely a cosmology of ‘immuno-containment’, and containment takes place across similar mediums (containment implies infinite divisibility); thus, to stress the ‘containment’ of the sublunary within the “hyaline”, as Milton does, is to impart some of the latter’s “crystalline” perfection to our own world. In other words, through its vitreous dialysis, this primum mobile acts as a vesicle purposed with separating Creation from Chaos: the happy harmony of this amniotic encasement — a placental harmony, therefore, between sublunary fundament and crystalline firmament and achieved through the shared medium of crystal perspicuity — announces the pre-lapsarian stability of Paradise Lost’s “new-made world”. Nonetheless: just as there was something wrong at the heart of the Crystal Pepsi venture, predestining it to fall, so too is there a blackening necrosis within this pellucid womb of Milton’s fictional cosmos.

[/note] Milton describes how God “as with a mantle did invest / The rising world of water dark and deep, / Won from the void and formless infinite”: he provides it with a protective skin, a form-suffusing “mantle”. As such, through wrapping the entire created universe in a “clear” liquid sack, this “crystalline ocean” becomes purposed with protecting the cosmos from the “loud misrule” of the Chaos that lies just beyond it [PL; vii.269, vii.271].[note]Chaos is, thus, analogical to the ‘energetic excess’ that Freud describes as facilitating the epithelial individuation of the originary vesicle, in his account of metapsychological abiogenesis, in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (Penguin, 2003).[/note] It is therefore a prophylaxis against an external chaoticism, and — as such — a spheroid cosmic immune system and metaphysical life support.[note]Cf. Peter Sloterdijk, Globes: Macrospherology, Volume II: Spheres (Semiotexte, 2014).[/note] A crystallic womb. Certainly, pre-Copernican cosmology is precisely a cosmology of ‘immuno-containment’, and containment takes place across similar mediums (containment implies infinite divisibility); thus, to stress the ‘containment’ of the sublunary within the “hyaline”, as Milton does, is to impart some of the latter’s “crystalline” perfection to our own world. In other words, through its vitreous dialysis, this primum mobile acts as a vesicle purposed with separating Creation from Chaos: the happy harmony of this amniotic encasement — a placental harmony, therefore, between sublunary fundament and crystalline firmament and achieved through the shared medium of crystal perspicuity — announces the pre-lapsarian stability of Paradise Lost’s “new-made world”. Nonetheless: just as there was something wrong at the heart of the Crystal Pepsi venture, predestining it to fall, so too is there a blackening necrosis within this pellucid womb of Milton’s fictional cosmos.

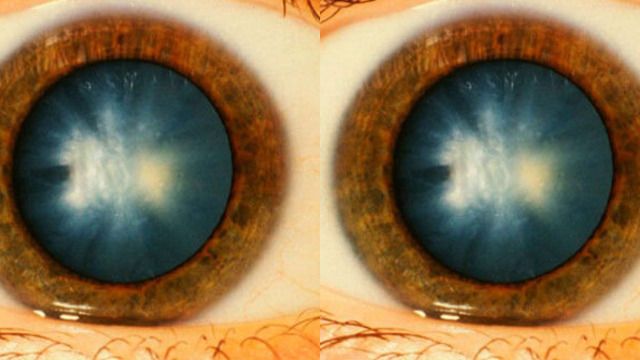

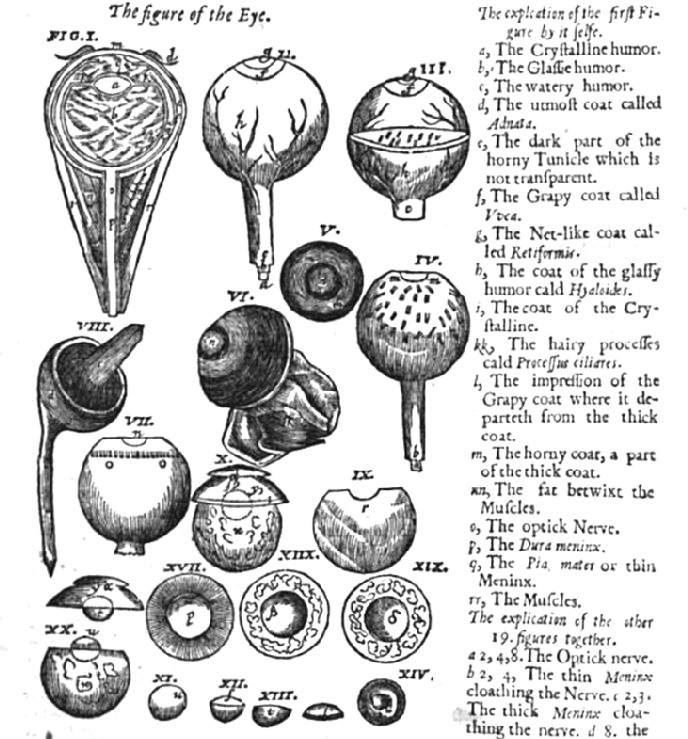

[/note]). Just as the planets are ‘contained’ within the life-support of the supernal realm, so too are our bodies, vouchsafed via the microcosm-macrocosm concordance of eyeball and firmament. ‘[T]here is a double firmament, one in the heavens and one in each body, and these are linked by mutual concordance’[note]Walter Pagel, Joan Baptista Van Helmont: Reformer of Science and Medicine (CUP, 2002), 99.[/note] This semantic entanglement between eyeball-strcuture and cosmos-structure is, unsurprisingly, ancient. As the Talmud, which Milton was familiar with, puts it:

[/note]). Just as the planets are ‘contained’ within the life-support of the supernal realm, so too are our bodies, vouchsafed via the microcosm-macrocosm concordance of eyeball and firmament. ‘[T]here is a double firmament, one in the heavens and one in each body, and these are linked by mutual concordance’[note]Walter Pagel, Joan Baptista Van Helmont: Reformer of Science and Medicine (CUP, 2002), 99.[/note] This semantic entanglement between eyeball-strcuture and cosmos-structure is, unsurprisingly, ancient. As the Talmud, which Milton was familiar with, puts it: