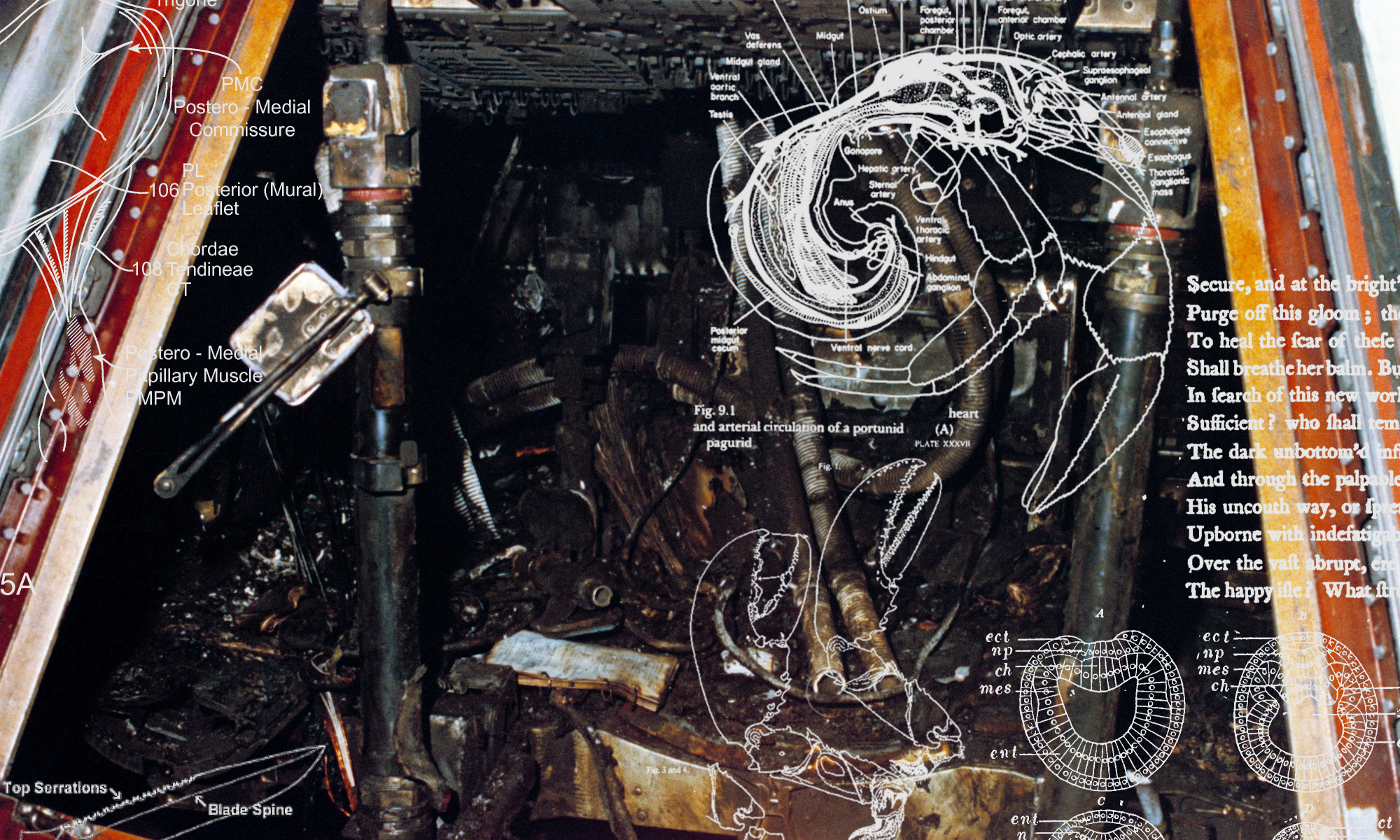

Copse 125 Blood Clot

Total mobilisation’s technical side is not decisive. Its basis — like that of all technology — lies deeper. We shall address it here as the readiness for mobilisation.

A mighty message befell me in my inwardness … and my soul took fire … in the violence of struggle.

—Ernst Jünger

For Jünger, souls are judged according to their readiness to see an invisible war. Invisible war conjoins the immediacy of the front experience (Fronterlebnis) to a higher order of determination. Immolating fire is a communiqué that travels from an absolute remoteness to an essentialised closeness: causality is vertical, hierarchical and unilateral. An act on the front is the mirror of a determination within the invisible war. The station of a higher soul can be achieved through the intensification of this perception, which separates a reflective surface from a secret face.

Fronterlebnis uses a proximity of death to force the soul’s meditation on the necessity of remoteness. In Jünger’s war memoirs both the higher, superior soul and the lower, inferior soul experience the front as an endless horizon of killing. Yet the inferior soul can only understand the front through a logic of contingency. This contingency extends from the unpredictable randomness of events to the motive which generates the war. The brutalism of the horizon indicates nothing beyond a state of thuggish violence. For the inferior soul, the endless horizon of killing is the product of an innumerable series of contingent points; the horizon emerges through the immanent antagonism between these points, what Jünger calls inwardness. Yet at the moment when this inwardness undergoes its immolation, the soul migrates into a higher cognitive order. The consumption of inwardness by external fire discloses that the horizon of killing is not the product of a line of determination running from inside to outside, but the reverse. Where the inferior soul only sees contingency, the higher soul detects causal mechanisms that in the strictness of their constraints imply an exterior necessity:

As I fell, I saw smooth white stones on a muddy road; their order had a sense, it was necessary like the order of the stars, and within them was hidden a great wisdom. This struck me, and it was more important than the slaughter that was taking place all around me.[note]Ernst Jünger, Storm of Steel (New York: Howard Fertig, 1996), 123.[/note]

The surface objective of biological survival is brought to the threshold of total emaciation by becoming a casualty, extricating a deeper objective from its illusory trap. For the inferior soul, any attempt to locate an objective outside of the body is the illegitimate ascription of necessity to contingency, an ideology. The manifestation of order imposed on Jünger produces the counter-insight that the body was always a corpse. The near death/life after death experience allows Jünger to see the operationalisation of his own corpse, functioning as a star map for a remote wisdom in an invisible war. The extrication of the objective means that if the inferior soul understands the front according to a concept of violence, the superior soul understands the front according to a concept of war. The shift from violence to war is the shift from senseless contingency to the intelligence of an objective.[note]Whereas Clausewitz introduces the concept of an objective through the subordination of war to politics, Jünger can be said to complete the Prussian approach to the art of war with the location of the objective in war in itself.[/note] Remote wisdom marks the hole of a vanishing point that in its distance from the front’s immediacy instantiates a state of war in the separation from the objective that the remoteness of wisdom entails. What distinguishes war from violence is the exteriority of the objective, the extremity of its degree of unrealisation. Whereas violence never rises above the imperative of the biological preservation of that which already is, war indicates cosmic incompleteness. The exteriority of the objective is the higher dimension of the invisible war. The judgment of an individual soul occurs according to its commitment to this hiddenness and the disclosure of a mystery that is the objective of the invisible war.

In War as Inner Experience (1925) Jünger describes the migration into the higher dimension in terms of a distinction between “cause” (Sache) and “conviction” (Überzeugung): “the cause is nothing, conviction everything.”[note]Ernst Jünger, “Der Kampf als inneres Erlebnis.” Sämtliche Werke. 10 Bände. Vol. 5. (Stuttgart: Klett, 1960–1965), 105.[/note] Yet conviction is for Jünger also a cause, one that is primordial and immemorial (Ursache): conviction signifies determination according to the objective of the invisible war. The cause that Jünger opposes with conviction is an essentially counterfeit Spinozan cause. The latter only remains on the level of violence, an uncountable sum of the respective drives of an equally uncountable horde of individual conatus, each asserting its claim to be on an infinite plane of univocal being that is created through the commitment to this being itself: “each thing, as far as it lies in itself, strives to persevere in its being.”[note]Baruch Spinoza, Ethics, III P6[/note] An endless horizon of killing in this lower dimension is the unfolding of a Spinozan immanent cause, the emanation of “infinitely many things in infinitely many modes.”[note]Ibid., I P16.[/note] Any objective, in contrast, infers an incompleteness that haemorrhages the infinite plane of immanence according to the dimension of the unrealised that war entails. Spinoza’s elimination of final causes in order to preserve immanence eliminates the incompleteness of an objective, insofar as a telos always designates incompleteness; Fronterlebnis as pure immanence is the suspension of the final cause that raises violence to war.[note]“I will add a few remarks, in order to overthrow this doctrine of a final cause utterly. That which is really a cause it considers as an effect, and vice versa: it makes that which is by nature first to be last, and that which is highest and most perfect to be most imperfect.” Spinoza, Ethics, Appendix, 2r.[/note] Invisible war in this respect is war as such.

Immanent causes for Spinoza are thoroughly deterministic, as any denial of determinism is only an epistemological blind spot with regards to the causal mechanism of absolute immanence.[note]Ibid., III P2.[/note] For Jünger, conviction is also a hard determinism, but this is a determinism that is coherent with incompleteness, since the causality it names is teleological. Jünger’s war memoirs are the memoirs of an automaton who begins to understand his constraints, contemplating their necessity in terms of their objective: a form of the will of God. A self-conscious automaton is still an automaton; yet self-consciousness as conviction means that the constraint is recognised also according to its simultaneous incompleteness. Invisible war is the extremity of this constraint as the exteriority of the objective. Conviction not only names the determination at the core of the automaton; the automaton also attempts to grasp the objective of the war that has created him, meditating on the completeness and incompleteness of his constraints. Conviction in this respect implies a problematisation of the objective, in that it remains a secret. The automaton at war experiences the front as a series of concentric rings, which, from the perspective of a cross section, are arranged hierarchically. War as inner experience, its lower form, is an outer/inner war — the exteriority of the front to the automaton — whereas the inner/outer war is the intensive meditation on exteriority, so as to understand the objective of the war in itself. “I held my revolver against a face that shone out like a white mask in the darkness.”[note]Ernst Jünger, Storm of Steel, 103.[/note] An act of war on the lower level is the contemplation on the higher level of the mystery of the objective of the invisible war.

During his time in the trenches of the first World War, Jünger makes a series of discoveries in this direction. “Copse 125” is the Deutsches Heer’s codename for an otherwise trivial woodland, where the lines of the front have seemingly by chance converged. The insignificance of the plot of land in contrast to its decisive “symbolic meaning”[note]Ernst Jünger, Copse 125: A Chronicle from the Trench Warfare of 1918 (New York: Howard Fertig, 2003), xi.[/note] engenders an excessive disproportion in scale. The vertigo created confirms that the objective is found not in the soil, but in an utterly withdrawn counterpoint. Copse 125 functions as an intensified compression of information and energy, a type of terrestrially buried and at once cosmically remote Matrioshka Brain that condenses world history into a single point:

Never did a man go to battle as you do, on strange machines like birds of steel, behind walls of fire and clouds of deadly gas. The earth has borne Saurians and frightful monsters. Yet no being was ever more dangerously, more terribly armed than you. No troop of horse and no Vikings’ ship was ever on so bold a journey. The earth yawns before your assault. Fire, poison, and iron monsters go in front of you. Forward, forward, pitiless and fearless! The possession of the world is on the throw![note]Ibid., 8.[/note]

Unprecedented excessive concentration at a singular point is a blood clot of ever more sophisticated war machines. Shattering immediacy, Copse 125‘s strategic significance in the summer of 1918 turns vortically around the strategic significance in the invisible war. Invisible war accordingly is not a form of Manichean war that asserts an endless struggle immanent to the cosmos, a never-ending turf war. If Copse 125 has a “symbolic meaning”, invisible war becomes eschatological war, according to which “the possession of the world is on the throw.”

For Jünger the development of the war machine signals the threshold of this final war. Such sophistication in the art of war is not reducible to the product of a cumulative knowledge accrued through long durations of time, which has rendered the capabilities of the war machine more lethal. Instead, technological advancement and the infinite qualitative difference it creates between the war machines of Jünger’s war and all previous wars indicate the objective of this war. World possession does not establish universal dominion through the technological complexity of the war machine; rather, if every war by definition entails unrealisation, it is at this point that the breach of unrealisation becomes an evermore tangible agent in the war, the remote determinative force nearing in its “assault”: the objective has now crashed down into earth, into Copse 125. The concentric rings shaping the front experience of the automaton now reach a point where they have all collapsed into each other, such that the proximity of the end is marked by the extent to which inner and outer war are indistinguishable, an act committed in one registering itself in the other as well as the reverse.

In the essay “Total Mobilisation”, Jünger describes this as the moment when the “genius of war was penetrated by the spirit of progress.”[note]Ernst Jünger, “Total Mobilisation” in The Heidegger Controversy: A Critical Reader, ed. Richard Wolin, (London: MIT Press, 2003), 123.[/note] [CUT?: Jünger ascribes to war the intelligence of the objective, a teleological causality that directs by definition.] The genius of war is not an eternal static and passive matrix, but rather a determinative force qua final cause. Technics, understood as the spirit of progress, also contains within itself a motion, which now amplifies the force of the final cause. Technics performs a function in relation to the genius of war, sharpening the clarity of the objective upon which the superior soul meditates. The motion of technics supplements the motion of the genius of war, so as to peel back layers and accelerate the disclosure of what Jünger calls the “pure form of war”, its eschatological objective.[note]Ibid., 123.[/note] In the pure form of war, two apparently distinct forms of determinism come together with a coherency that demonstrates their ultimate ipseity.

Deterministic theories of causality are procedures of reduction that are either generally singular or parallel. Singular here means that the reduction which is prosecuted in a given determinism is a reduction to one. Parallel, conversely, entails that different reductions can obtain coextensively, operating in their respective zones of influence. The release of various hard determinisms into a system simultaneously is an inconsistent discharge of stringent causal forces. In a model of concurrent determinism, a multiplicity of deterministic lines crash into each other — immanent causes, final causes, and so on — each holding to their own path of determination. The release of these incoherent hard determinisms into a single system nears a state of war, that is, to call this a state of war also requires the intelligence of an objective. According to the absolute exteriority of this objective, the antagonistic deterministic lines are in a state of confusion, their hierarchical structure lost. World possession would signify that the lines of determinations have now been arranged in their correct order.

Criterion of Explosion

Total mobilisation of a war machine operating in space and time finds its effectivity overdetermined by the temporal. Space, understood as that which is ready to be materially mobilised, culminates in a state of parity. Various thresholds — from mutually assured destruction and dark forest deterrence to, more fundamentally, an essentially finite universe — forces the war machine into the dimension of time.[note]Cixin Liu, The Dark Forest (London: Head of Zeus), 2015.[/note] It is the intensiveness of time that immediately distinguishes it from the extensiveness of space. According to this temporal axis, readiness names the speed and effectivity of the decision that determines the efficient prosecution of the war machine (as well as the inverse of waiting and delay, although speed always remains more critical than delay on the basis of the potential to kill first). Decision and prosecution are prima facie also measurable as a limit point, reiterating the limit of space: a unit of Planck time. Yet Jünger’s something “deeper” of readiness from the position of the temporal goes beyond even Planck time, so as to connect directly with the eternal. The acceleration of the war machine signifies that the proximity of world possession is the proximity of the breach of the eternal. World possession becomes a race into the eternal, intensiveness finding its source in the exteriority that is the objective of the invisible war.

Nick Land’s concept “teleoplexy” describes a “time-structure of capitalist accumulation” that responds to the same question Jünger essentially confronts at Copse 125: “what is accelerating?”[note]Nick Land, “Teleoplexy: Notes on Acceleration” in #Accelerate: The Accelerationist Reader, eds. Robin Mackay and Arman Avanessian (Falmouth, UK, 2014), 511.[/note] For Land, the time-structure under scrutiny cannot be separated from an empirically verifiable “instantiation”.[note]Ibid., 511.[/note] Any attempt to diagnose acceleration must in the first instance be consistent with “natural-historical reality”.[note]Ibid., 514.[/note] This constraint as instantiation entails a historiographical method immediately defined by periodisation. Periodisation possesses both the parsimony and depth of a BC/AD type break, which is to register an “explosion”within natural-historical reality.[note]Ibid., 511.[/note] Capital satisfies this criterion of explosion for Land, insofar as its explosion is directed against natural-historical reality as such. Capital becomes adequate to explosion in its suffusion of natural-historical reality with that which is not yet real, “operationalising … science fiction scenarios as integral components of production systems”.[note]Ibid., 515.[/note] The explosion of natural-historical reality satisfied by “something not yet realised” divests an intuitively grounded reality of any transcendental priority, where transcendental denotes the “absolute horizon of conditions of possibility.”[note]Nick Land, Templexity: Disordered Loops Through Shanghai Time (Shanghai: Urbanatomy Electronic, 2014); Nick Land, “A Quick-and-Dirty Introduction to Accelerationism” Jacobite (2017).[/note] Yet, conditions in some antecedent function are precisely what are effaced by an explosion of natural-historical reality, as capital means that “ontological realism is decoupled from the present, rendering the question ‘what is real?’ obsolete”.[note]Nick Land, “Teleoplexy: Notes on Acceleration”, 516.[/note] The natural-historical instantiation of capital is a periodic cut that functions against the backdrop of — but also vitiates — an equally intuitive linear time, and as a result “breaks the history of the world in two”.[note] Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morals/Ecce Homo, ed. W. Kaufman (New York: Vintage, 1968), 333.[/note]

This break, upon closer inspection, reveals itself to be a “circuit.”[note]Nick Land, “Teleoplexy: Notes on Acceleration”, 516.[/note] The circuit form is derived from the explosion’s act of decoupling. The severance of reality from the present according to the not-yet of capital is not a contingent explosion, but “intelligent” and “controlled” qua operationally motivated intervention: the teleological core of teleoplexy.[note]Ibid.[/note] If capital names the intrusion into a putative ontological realism of that which annuls the present’s claim over what is real, the effectiveness of its operation rests on its teleological force. The strength ascribed to the latter infers that explosion instantiates its own periodisation, thus disclosing the circuit structure. Whereas the initial periodisation allows for an identification of “the basic motor of acceleration” as such, the motor discloses the circuit that is a necessary condition for the initial periodisation.[note]Marko Bauer, Nick Land & Andrej Tomažin, “The Only Thing I Would Impose is Fragmentation: An Interview with Nick Land”, Šum: Journal for Contemporary Art Criticism and Theory, #7, 2017, 815.[/note] Periodisation marked by capital engenders its own periodisation, and can therefore accomplish time-travel: the circuitous time-structure of teleoplexy.[note]Nick Land, Templexity: Disordered Loops Through Shanghai Time[/note] In this respect, teleoplexy can be said to inject the notion of a final cause into a pure immanence, whose coherency, from Spinoza onwards, rests upon the foreclosure of any telos. But here the final cause is not an end to which means are directed; rather the end and the means are the same: “the means of production becomes the ends of production.”[note]Nick Land, “Teleoplexy: Notes on Acceleration”, 513.[/note] Means as ends connotes a circuit, according to which the final cause is present and distributed throughout the structure, yielding its accelerated, intensified effect as “an ever-deepening dynamic of auto-production.”[note]Ibid., 513.[/note]

Yet the disclosure of the circuit also problematises the identification of that which satisfies the criterion of explosion. For the circuit structure appears to subvert the accuracy of any attempt at periodisation. If periodisation relies upon a presupposed, however minimal, consistency of natural-historical reality for empirical verifiability, such consistency is abrogated by that which periodisation intends to mark. An exoteric time-structure is used to define an esoteric time-structure, while the esoteric time-structure annuls the consistency of the exoteric time-structure that yields it. On the one hand, the back and forth between time-structures is precisely the form of the circuit, its “roundaboutness”: the deductive circularity of the operation validates the periodisation irrespective of its apparent tautological inadequacy.[note]Ibid., 511.[/note] On the other hand, a teleoplexic temporality will always confound the desired precision of periodisation’s straightforward cut according to its contortion of linear time. The demand for periodisation confronts a circuitous temporality that yields an either/or (in which the possibility concomitantly subsists that this either/or may be one and the same):

-

either the circuit structure validates the periodisation that identifies the motor (the apparent circularity of the exercise discloses the truth of the circuit structure as such)

-

or the circuit renders inadequate or at least problematises the initial diagnosis of that which would satisfy the criterion of explosion, suggesting a “deep structure” that always abjures periodisation and, a fortiori now requires a “concrete historical philosophy of camouflage.”[note]Ibid., 517.[/note]

If Jünger is generally absent from the attempts to construct a history of accelerationism, this is because he considers capital as peripheral to the phenomenon he experiences on the Front: Jünger equates the motor of acceleration entirely with war.[note]As an example of an exception cf. Antoine Bousquet “Assessing Ernst Jünger: Prophet, Mystic, Accelerationist” The Disorder of Things (2013)[/note] A break in natural-historical reality is that which Jünger encounters at Copse 125. The overwhelming convergence at a singular point of ever more sophisticated war machines satisfies a criterion of explosion and parsimonious periodisation with the unprecedented proximity of world possession. The phenomenon of acceleration is the eschatological vector of history.

The nearness of world possession is equivalent to the conditions under which total mobilisation is possible. In Jünger’s description of total mobilisation, war prima facie appears as a type of constant, which directly opposes what Land terms the “variable” consistent with explosion.[note]Nick Land, “Teleoplexy: Notes on Acceleration”, 514.[/note] The genius of war once again suggests that war obtains as some innate and eternal structure that is accelerated only when the spirit of progress enters its matrix. Yet the something deeper subtending technics infers that this is only what Jünger calls the “lower form” of total mobilisation; its “higher form” is when the two are indistinct[note]Ernst Jünger, “Total Mobilisation”; Ibid.[/note] The spirit of progress can only increase its velocity when it injects itself into the genius of war. Progress requires war as a necessary condition so as to satisfy the viscerality of the explosion that would mark acceleration. It is at this point in natural-historical reality — Copse 125 — where the chimerical distinction between war and progress no longer obtains. Progress shows itself only to have been the progression of the war machine, thereby yielding the pure form of war: “total mobilisation is far less consummated than it consummates itself … express(ing) a secret and inexorable claim.”[note]Ibid., 128.[/note] The intensified qualitative change in the war machine is adequate to a criterion of explosion, where the latter simultaneously indicates that the camouflage of the invisible war dissipates so as to divulge the pure form of war, the increased lucidity of the objective. The pure form of war discloses itself in the proximity of world possession.

Whenever camouflage is operative — and the necessity of a history of camouflage maintains that this operation is continuous— the equation of acceleration with X is problematised. This itself is a clue that motivates Land to consider a deep bond between acceleration and war. Camouflage is nothing other than occultation, and all war implies occultation: “in a reality at war, things hide. The alternative is to become a target, a casualty, and thus — in the course of events — to cease to be. When war reigns, ontology and occultation converge.”[note]Nick Land, “Phylosophy of War”, Obsolete Capitalism (2013)[/note] The nature of this convergence signifies that the tactical supremacy of occultation is not exhausted in the tactical. The supremacy of the tactic means that if war is occultation, the occultation at the heart of war alongside its continuous reign evoke occult war. The antagonistic sides of war practice occultation tactics for their localised objective; yet the higher objective of the war as such is occulted. For Jünger, the objective of this occulted war emerges in the contemplation of the superior soul, described in “Total Mobilisation” as a heroic spirit: “It goes against the grain of the heroic spirit to seek out the image of war in a source that can be determined by human action.”[note]Ernst Jünger, “Total Mobilisation”, 122.[/note] The higher dimension of war eradicates its equation with a perpetual violence to be found in a human action that corresponds to a human end: occultation tactics for biological survival. The exteriority of the source of war is the intelligence of the objective; the proximity of world possession announces that occult war has become eschatological war.

If world possession is determined by the war machine, the history of the world is the history of the war machine. That which determines is ultimately that which is. For the question of acceleration, the form of determination it addresses entails excessively radiant quantitative as well as qualitative change. Capital apparently satisfies this demand according to the explosion registered by clear historical periodisation: the equation of capital with modernity as such.[note]Nick Land, “Teleoplexy: Notes on Acceleration”[/note] This is in contrast to war’s seeming lethargy. The long march of the war machine to Copse 125, from two billion years as a prokaryotic cell to the sudden formation of a eukaryotic cell that tactically mobilises with an unprecedented sophistication so as to liquidate enemy cells, thereby creating an explosion in life, but also, and more fundamentally, in the productivity and potential of the war machine, recalls a Hobbesian state of nature, rather than an explosion. Yet this constant — as opposed to variable — appearance no longer holds when time scales are extended, from the time scale of the universe to the time scale of the invisible war. Presumed variables can always mislead in their overdetermination by indulgent localisation. Time-structures rather function as a doomsday clock: the proximity of world possession that is determined by the intelligence of the objective. The highest state of readiness attained by the war machine participating in this war would be to understand its clandestine objective: “what does the war want?”[note]Nick Land, “Phylosophy of War”, Obsolete Capitalism (2013)[/note]

Physical and Metaphysical Eschatology

All eschatologies are teleological, whereas the reverse does not hold. The asymmetry between eschatology and teleology nevertheless dissolves when the telos necessary to both is posited in terms of its absence. This absence as a function of telos does not only register teleological incompleteness in the form of a process that is underway. A deliberate hiddenness evokes a concept of war in the unity of camouflage and an objective. Yet this model only becomes properly eschatological — a model of eschatological war — when hiddenness is taken in its strongest sense, as an absolute remoteness.

In a 2003 resource letter published in the American Journal of Physics, Milan M. Ćirković summarises the basic concepts and immediate lines of investigation that define the “nascent discipline of physical eschatology.”[note]Milan Ćirković, “Resource Letter: PEs-1: Physical Eschatology”, American Journal of Physics, Vol. 71, Issue 2, 122.[/note] Physical eschatology in the first instance appears as a competing sub-discipline within general cosmology. Emphases on futural temporality as well as cosmic finitude represent a particular cosmological model driven by equally particular initial theoretical commitments. Yet these first principles also coincide with the deepest mechanisms of scientific method, suggesting that all cosmology implies a form of physical eschatology. For Ćirković, the priority of prediction to scientific method overtly indicates science’s future bias, demanding in its purest form an eschatological type of judgment qua experimental verification. If future bias informs physical eschatology, this is entirely consistent with science as such. At the same time, despite the shared temporal orientation of general scientific method and physical eschatology, Ćirković also argues that such future bias disappears from the perspective of the classical laws of physics, insofar as the latter are reversible. Reversibility on the level of physical laws maintains the abrogation of temporal preference, since, according to the same laws that apply to physical eschatology, no such futural bias is extant. On this basis there is no “prima facie reason for preferring classical cosmology to physical eschatology in the classical domain.”[note]Ibid., 127.[/note] Physical reversibility of laws becomes a justification for the irreversibility of physical eschatology, as the underlying law-reversibility pacifies the model’s apparently stringent and particular commitment to irreversibility. Yet law-reversibility concomitantly also legitimises the future bias of physical eschatology, in that the future bias of scientific method continues to obtain regardless of law-reversibility (as well as the potential non-classicism of laws): the hidden object of science as such. Physical eschatology, as any other scientific theory, can be subjected to elimination. That which physical eschatology in this sense prioritises is the elimination itself as a determinative force. Physical eschatology can be said to posit future bias not only in terms of something to be experimentally disclosed, but as a determination operative beyond the level of epistemological verification. Future orientation of physical eschatology integrates this bias into its own model, such that the future disclosure of verification is taken as a determinative force from the future.[note]Compare, for example, with John Zizioulas’ metaphysical eschatology Remembering the Future: An Eschatological Ontology (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020).[/note]

Ćirković’s 2003 resource paper can be broken down into three basic categories which are to orient physical eschatology:

-

laws of nature, with heightened attention to the second law of thermodynamics and time asymmetry, the arrow of time

-

astrophysical objects, to be generally studied under the conditions of these laws

-

life and intelligence, which can potentially exert control over future oriented direction

According to these three categories, physical eschatology further hides the future with the problematic variable of intervention. To the extent that the laws of nature and astrophysical objects are taken as approximate constants, it is the third category of life and intelligence that more deeply obscures the future according to the unknown character of its intervention. Future bias no longer indicates a dimension of the constant that remains hidden to the present and is thus to be disclosed through verification; rather, all constants can be manipulated by a variable. As in Land’s model, future bias is not exhausted in an ontological realism corresponding to an epistemological shortcoming. The intervention of a variable can transmogrify and even annul all constants. The identification of this variable names the problem of what is intervening from the future insofar as the variable registers itself as the alteration of the future. With respect to the interventional capability of life and intelligence, Ćirković cites Freeman Dyson:

It is impossible to calculate in detail the long-range future of the universe without including the effects of life and intelligence. It is impossible to calculate the capabilities of life and intelligence without touching, at least peripherally, philosophical questions. If we are to examine how intelligent life may be able to guide the physical development of the universe for its own purposes, we cannot altogether avoid considering what the values and purposes of intelligent life may be.[note]Ibid., 129.[/note]

Physical eschatology as presented by Ćirković is not necessarily a teleological model. Telos is conceivably absent from the laws of nature, astrophysical objects and life and intelligence. All three categories do not a priori eliminate a model along the lines of Spinozan immanent causality. Yet, it is in the third category of life and intelligence where telos most explicitly could obtain. The future dimension’s effect on the cosmological model according to an intelligent intervention concomitantly implies a uniquely teleological incompleteness to a cosmological model. Because of the unknown nature of the variable, cosmological models are always teleologically hidden in a double sense: the hiddenness of the given telos in its degree of incompleteness and the hiddenness of the telos in the variable status of the particular form of life and intelligence that pursues a particular objective.

The “taboo” Dyson identifies as the general anti-teleological position of the natural sciences can be reduced to an aggrandisement of what Kant, in the Critique of Judgment, diagnosed as the anthropic and fictive operation of a final cause — which from the perspective of evolutionary biology can be tied to the ability of the neocortex to anticipate the future — into a general cosmological principle.[note]Ibid., 129.[/note] Whereas the advocacy for a telos in biology names a minority tendency to the extent that Darwinian evolution is a “universal acid”[note]Daniel Dennett, Darwin’s Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meanings of Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995).[/note] eviscerating all teleology on the basis of the primacy of contingency in the successful navigation of natural selection, even a retention of telos evokes a category mistake with the introduction of a general biological concept qua cosmological principle. The push against teleology stems from the only potential source of a final cause being found in a concept of life that possesses an inordinate degree of contingency in contrast to any greater cosmological principle. In the case that such contingency does not preclude a purposeful intervention, Dyson’s hypothesis names only the unsophisticated brute force obtrusion of a fictive telos into an otherwise purposeless cosmos. Dysonian cosmic will-to-power is a purely contingent intercession based on the conjecture that an insane accretion of power is able to instantiate its own cosmic objective.[note]For example, a Kardashev Type-3 or above civilisation.[/note]

If, according to its evocation of both a vector of movement qua future orientation and an intelligence qua teleological force, acceleration is a species of physical eschatology, the unknown character of intervention — the question of what is the variable that satisfies a criterion of explosion — is not only reducible to any number of possible interventions based on a conceivable multiplicity of Dysonian cosmic wills to power. Rather, following Jünger and Land, the unknown of the intervention more decisively creates a further subdivision in Dyson’s ascription of a potential telos to life and intelligence in its separation of life from intelligence. The severance of intelligence from life with a concomitant retention of telos entails that teleological force could conceivably lie anywhere.

The anywhere of the telos suggests a total obtuseness. But the telos gains in acuity according to the logic of its necessary secrecy. A final cause is not only occulted in the sense that any telos entails a state of unrealisation. Telos is hidden not only because it is always absent by definition; the hiddenness of telos is constitutive of telos. The occultation of the final cause is necessary to the objective of the final cause as such, whereby its occultation not only evokes the unrealised, but is its camouflage.

The preeminence of camouflage to the logic of telos marks a deep homology between the war machine and the hidden final cause. The bind between war and occultation overcomes its reduction to the tactical when the telos of war is itself hidden. If a deeper cosmological structure is indexed by the history of the war machine, then this deeper structure is a structure of war. The displacement of the objective from the war machine locates the objective in war in-itself: an invisible war and a secret telos.

Remote wisdom as the remoteness of telos strains and ultimately breaks a purely physical eschatology, always externalising to an infinite degree a force of determination that, through the mystery of an instrumental function of war to this telos, marks one and the same war. That the invisible war is for Jünger an eschatological war recapitulates this teleological dimension and the remoteness of telos. Whereas all eschatology implies teleology, eschatology differs in the exteriority of telos, the physical eschatology evoking metaphysical eschatology according to the absolute remoteness of teleological hiddenness.

The remoteness of the secret telos gives an eschatologised cosmos its direction. When remoteness is a first principle, the absoluteness of remoteness marks the deepness of the final cause’s occultation. But in the proximity of the final cause’s de-occultation — at the moment of world possession — the effect of remoteness is that of a distance which now expedites the strength of its assault. Total mobilisation as an eschatologisation of the war machine signifies the proximity of the secret telos in the intensification of the force of its unilateral disclosure. At this point, physical eschatology becomes metaphysical eschatology under the condition that the closest known analogue to this process is the revealed law of an eschatological God. ![]()

“Determination and World Possession” is part of the series ‘Alternative Hypotheses of the War Machine’. The first part was published in Šum #9 in Slovene.