“I am not I; I am but a hollow tube to bring down Fire from Heaven.”

—Louis Hemmingen, epitaph

“What happened to St. Louis?”

“I never heard of it.”

“How do you get down to the lake?”

“Oh, there is a cave system…leads down to grottoes.”—William S. Burroughs, The Western Lands

Portent

The sun rose the color of wax this morning against a shifting grey sky. By noon it has faded to slate, granite grey, with storm clouds mounting in the west. A soft rain at first. By the time I leave my apartment, the wind is throwing trash and leaves, sending it skittering for windbreak corners. When I get out of my car rain rips at my face like needles. As I walk to the café, I keep my head down, mapping my travel against the reflected light caught in the rapidly freezing water pooling on the sidewalk. Red yellow white blue cycling as I pass by storefronts, homes.

Opening the door to the café invites in a shot of the furious gale outside, prompting cruel glances. I order a black coffee and stammer thank you, before finding a table toward the back. A TV bolted to the wall silently plays CNN, captions lagging behind, the poor encoding making a grotesque mockery of speech.

I settle in and wait for Peter, scanning the room between drinks of coffee that burn my tongue. The light inside is too bright, too clinical, especially in contradistinction with the premature night outside. Over the murmur of conversation, I can hear the soft roar of rain and mechanical systems. A branch tick-tick-ticks staccato on the glass window to my back. 15 minutes gone. I can feel my frustration mount with every second, both with Peter’s lateness and our reason for meeting — my own intellectual torpor. Hopefully Peter can help. I have only met him briefly before, haven’t talked to any advisors after what happened to Maggie.

After a few minutes, Peter enters, rain sluicing vantablack off his jacket. At the counter, I can hear him order a tea. My coffee is already going oily in its paper cup. He spots me and waves, threads his way through the narrow tables, dress shoes tapping on ceramic tile. He slides into the chair across from me, makes genial small talk about the weather for a few minutes, adding sugar to his black tea.

After a pause, he looks up at me with renewed seriousness. “How’s the dissertation going?”

I pause for a moment. Sigh. “I’m a little stuck, truth be told.”

“Um. Hold on, don’t remind me…uh…mid-century modernism in St. Louis? Public housing, that kind of thing?”

“Right. Kinda.”

“Well, what seems to be the problem?” He pulls out his tea bag, sets it on a napkin.

“Well, I guess I’ve hit a wall,” I begin. “Everything available is too general, too banal. The archives themselves are a mess. Almost nothing is digitized, or even catalogued really. Just no one seems to care. I can’t even get a thesis formulated outside of doing some kind of historical survey.”

Peter nods knowingly. “It’s harder in these small cities, these mid-level places like St. Louis. Getting archives in shape and keeping it that way is basically a function of what your intern budget is.”

“Yeah. Every time I go to the City Hall records, they’re so overworked I don’t think they’d ever clean anything up unless I volunteered or something.”

“Why don’t you?” Peter muses. Then abruptly, he snaps to attention, seemingly having just recalled something. “Hold on one moment,” he says, “I have something for you,” and reaches into his bag. “You won’t find this in the archives, that’s for sure.” He treats the extracted object with delicate reverence as he places it on the table.

“Take a look at this.”

It’s a book. Titled City of the Arch, written by a Fatima Duré. I’m a bit unimpressed: it looks like cheap schlock, the kind of thing you’d find in the grocery store checkout line or the New Age section at a chain bookstore. The cover is pure bombast, all flashing golds and blues. The inner jacket begins, “For the first time in print…”

I look up and pause, trying to read Peter’s face. He’s utterly impassive. I can’t help but wondering if this is a joke, but decide to be civil. “What’s the story with this thing?”

“Well”, he mumbles, “I’m not quite sure. My friend is a historian on contract with the Natural History Museum. I had mentioned offhand I was meeting with a student into, and what you’re interested in, she dug this out of the archives and let me borrow it. I didn’t get very far into it but, uh, it’s on St. Louis history, and apparently has something to do with your thesis. She was very adamant this would be very helpful for your work.”

“Well, thanks,” I mutter, setting it on the table facedown. The entire back cover is dominated by Fatima’s author photo. The author is a small, hunched woman sitting in a simple wood chair, with enormous glasses set above her beatific smile. Her body is obscured in countless scarves, blankets, headwraps.

“Maybe it’ll be just what you’re looking for,” he grins hopefully.

The rest of the conversation is short. Any questions I ask seem to be met with mounting impassivity, terminating into an interval of concluding small talk. Peter theatrically checks his watch and stands up. “I have to go”, he placates. “Really sorry. I’m actually getting out of town for a few days. Have to catch my flight.” All I can do is nod passively as he collects his things, hurriedly drinking the last of his tea.

“Maybe Book of the Arch can at least be a bit of light reading over the weekend!” he suggests, half-cheerily, on his way out the door. The last of his words are nearly erased by the howling wind outside.

What a waste of time. This stupid fucking book. I flip through, starting in the middle and letting the pages fall. In the top corner of the inner cover, there’s a small, neat scribble, reading:

If Lost Please Return.

Emily Tocz

1918 Division St.

There’s no title page, no Library of Congress info, not even publisher information or a date. There’s just a blank page, and then the header CHAPTER 1, which begins with the line, “For the movement of peoples I have come to you.”

A chill. I instinctively look to see if someone opened the door, but the café is silent and still as ever, the doors shut tight against the storm outside. People’s faces lit by the phoresence of their laptops.

A voice in my head, a wicked conscience. Buried deep in the occulted backbrain. It warns me: Be careful. Barely louder than a whisper.

Careful? Sure. Of this ridiculous thing.

“And since I have come, the working has already begun. Ours is a history out of joint. Let us speak of the Empyrean Proceeding, the great project of the Aeon and of its End. Let this book be a message for those that will come beyond, for the Children of the Future. For they must be made to understand why he did what he had to and what he was bidden, within the structures of the age.”

I flip a few pages ahead, to something that looks a bit more coherent. In the middle of page 13:

“In 1948, infuriated with Karl Germer’s leadership after the death of Crowley, Louis Hemmingen began holding small colloquia in the basement of his South City home. These initiates eventually began referring to themselves as the Church of Starry Wisdom, meeting under the sign of the Saturnine (later Empyrean) Arch. With the Church, Hemmingen became increasingly obsessed with the Liber 474, a text written by Crowley and which announces itself as “the Gate”. The figure of the gate, borrowed from Royal Arch masonry, would come to consume Hemmingen as his star rose in his professional life…”

Ok, this is actually interesting. Or at least, it makes slightly more sense. I actually know the name Louis Hemmingen, vaguely: St. Louis Housing Authority Director in the 1950s, presiding over the heyday of urban renewal, generally remembered by history as a racist asshole and not much else. Not really of any particular interest — just one of a priestly bureaucratic class of lifelong public servants of the type that seemed to be a dime a dozen in the postwar period. When I look him up, his Wikipedia entry is basically empty, a sedate listing of facts: born to a high-level Purina exec and a homemaker, graduated from Washington University with a degree in architecture, became a planner in Pasadena before returning home at Bartholomew’s request for appointment to the Directorship of the Housing Authority. His exploits in St. Louis read like a laundry list of urban renewal initiatives: slum clearance (especially for the Jefferson Memorial Park project), public housing project construction, the works. No mention of any Gate or Empyrean Arch…

“…as his star rose in his professional life”. This seems like a bizarre description of the career of a technocratic company man now entombed in the dustbin of history, whose only legacy is blundering his way toward the utter collapse of St. Louis’ as a city altogether. Is that what counts as a “star rising”? Clearly, Duré isn’t urban faculty anywhere…

The Liber 474. Karl Germer. Both of these names are strangely intriguing… especially in relation to the name Crowley, which I’m guessing is the famous magician, Aleister. The Liber is easy enough to find online (assuming I have the right one — this one is titled Liber OS ABYSMI vel DAATH sub figura CDLXXIV).

But underneath the overwrought title, the first line is plain enough: “This book is the Gate of the Secret of the Universe”.

I have been becoming increasingly uncomfortable as I read, every word grasping at me with icy importance. This sensation suddenly crests, becomes unbearable. I realize I have been shivering badly. The wind outside must be worming in through the windows, under the door. The book itself feels frozen, the cover a skein of ice.

I need to get out of here and calm down. I slip the book in my bag and wrap myself in my coat. When I step back out onto the sidewalk, the air is thick with ice, cutting into my face. All the other figures I pass on the walk back to my car are shrouded, faces couched back deep under shadowed hoods. They walk with harried purpose, loping inhuman in and out of the pools of light from streetlamps.

When I chance a look up, the clouds are piled high against a black sky, rising into boiling, noxious infinity.

Call to mind

When I get home that evening, I’m still thinking about the gnomic passage on Hemmingen, Germer, and Crowley. Let’s pretend it were true, I tell myself. What would this mean? Hemmingen, boring civil servant. I recall reading some article a few months ago that referred to him as “St. Louis’ Robert Moses, but as evil as he was dull”. Kind of hard to square that with the allusions in Book of the Arch, however: Hemmingen moonlighted as the priest of some crackpot church? The hypersecular pragmatism of Moses’ blight-burn-build axiom lashed to apocalyptic theology and weird magic. I wonder what would happen if I cited it in the dissertation, tucked it into a footnote or something: “Oh yeah, Hemmingen? Sure, he was a boring racist weirdo, but did you know? He also was some type of sorcerer…”

Murmurs.

I’m hearing things. I need to sleep. But I can’t — the Book of the Arch seems to be beckoning me to read on, demanding I continue. I look over at my stack of books to read, piled messily in the corner, and sigh. Far too much to do.

The Housing Question will be there tomorrow, I tell myself. Take a night off. If you can call it that.

I go sit at the kitchen table and reread the passage I read earlier. First order of business is to figure out who these other people are, beginning with Karl Germer. When I look him up, the first result is some ancient page naming him the “successor to Crowley in the Ordo Templi Orientis, Frater Saturnus, personally appointed as Outer Head by Crowley after his death”. That’s not much of a help.

The second result is an article, blessedly written in some approximation of normal english by a British O.T.O. “excommunicant and poet” named Kenneth Grant. The article is titled “On Love Lost: The Sad State of the Ordo Templi Orientis”, denouncing Germer as a “charlatan” and “extracephale, a rotting Head”. Hemmingen’s name swims up out of the noise-pattern of text. Grant quotes him, no less. Further, Grant is speaking specifically about Hemmingen’s Church of Starry Wisdom as some type of schismatic precedent. “Hemmingen’s letter to me sums up my position exactly: ‘Following Germer’s ascendency, I became ashamed of my status in the Ordo Templi Orientis. Yes, I broke away, ensnaring and ensuring the good name of the O.T.O., of Crowley, of Parsons, preserving them and smuggling them into the future under the Empyrean Arch.'” A few lines later, Grant indicates his allegiance to “Hemmingen’s model of a diffuse, patchwork faith” as a counterweight to “the old sin of the unitiated and monomythic hubris”. He ends the essay sketching out some tenets for a new organization, a “Typhonian O.T.O… a friend to Hemmingen’s American church…”

Flipping back to Book of the Arch, Duré continues the passage: “Hemmingen did not act alone in carving out his sanctum in the Kingdom. There were others, and indeed others beyond them. But one man emerges as a particular friend and mentor of Hemmingen’s Empyrean Proceeding: Harland Bartholomew, then VIII° in the American O.T.O. It was the agape shared between him and his mentor that animated and sustained him, a perfect closed loop of masterful willpower. Harland Bartholomew was the law, and Hemmingen, working under him, but fiery and driven, supplied an infinite engine of will. The two were exemplary of what is possible within the Current — artists and scientists both, a masterful syzygy, perfect cosmic twins.”

I have to laugh at this one. There’s just no way. Harland Bartholomew? Urban renewer sui generis, the father of the field of planning in general? If Hemmingen being a secret mystic was one thing, Bartholomew was quite another…

I give Bartholomew a cursory look, specifically sniffing for any occult-seeming connections, only to find an immediate dead end. Surprisingly (just like Hemmingen) the amount of data available on him is extremely small. The bulk of the search results are his obituary, or longform articles on the urban renewal he championed. On JSTOR, the first substantive option is a paper entitled, “’The Whole City is Our Laboratory’, Harland Bartholomew and the Production of Urban Knowledge”. The title seems interesting enough to warrant a read. Skimming the text, I find a pertinent quote: “’In the science of city planning,’ Ford wrote in 1915, ‘the whole city is our laboratory. All its facts and symptoms are more or less under observation and in play, but the expert city planner soon sifts the significant from the less important.10’” Endnote number 10 is even more pertinent, reading:

“Bartholomew, a life-long Mason, often referred in his private letters to the notion of ‘tesselation’. One can see why. To Masons, the warp and weft of contemporary life is represented as a chessboard — and tessellation, then, is the checkered patterning. The crucial turn for a Mason such as Bartholomew is the acquisition of an analytical & scientific critical distance, a view to a process of data control, of cybernetic authority, allowing for the careful movement of pieces across the board.”

The power of tessellation. To make the “whole city our laboratory”. The word laboratory seems wrong in that typical, technocratic way — the city isn’t a controlled project with a defined set of variables. “Moloch, whose mind is pure machinery!” No, no.

“What sphinx of cement and aluminum bashed open their skulls and ate up their brains and imagination?”

Moloch is the city. A massive sorting machine, a god of eugenics slaved to a meat grinder. A flesh engine. All that’s necessary is for operators like Hemmingen, or Bartholomew, to stick the key in and break it off.

Moloch by another name. Choronzon.

I put down Book of the Arch and go outside to the small balcony off the kitchen, 3 stories above the frozen mud of the yard. The wind threatens the flame as I light a cigarette. The trees have been stripped by the storm, leaves fluttering in spiral columns up over houses. Embers peeled off the end of my cigarette join the dance, lofted higher and higher against the flat black sky. My heart is beating quick and erratic, my mind still plagued by the Book sitting on the table inside. Maybe I really can mine it for something useful.

I drown my cigarette in a flowerpot on the railing, overflowing with sooty rainwater. I check the time. 9:30. I had told friends I would meet them for a show. Better keep my promise.

I get to the bar 15 minutes later. The band is unlistenable shit, as I feared. As I get drunker, the leering mental spectre of the Book gives way to a full-blown haunting. Hemmingen and Bartholomew stalk my brain, conjoined in abominable shapes, joined at the head, the hips, fractalizing into pixelated worms. I almost see them everywhere, lurking in crowds, disappearing around corners. My body feels too heavy, and with a creeping dread I realize the chill in my spine from the café earlier never left. Instead it has rotted into my bones, seeped into my muscles, begun to leech black dread. I keep drinking. Wonder if I can poison it.

After the show, I’m talking to Sarah, smoking on the dark patio, huddled under the dull eye of a whirring busted heat lamp. I’m five beers in, a sixth in hand.

More people come out to join us. She starts talking about her thesis, as always. Some type of Benjaminian flânerie thing that frankly, escapes me. I’m jealous as hell, I admit. She’s somehow scammed funding out of enough people to go on research trips, all from recording her ‘walkabouts’. She’s gotten write-ups in Places, Log, and other publications I don’t even know about. She’s shopping her dissertation to publishers already, has Routledge talking last I heard.

Meanwhile, I can’t even break 20 pages, and my summer plans currently are to just boil alive in my South City apartment. I just let her talk, hope I’ll soak up her good fortune or something by keeping a pleasant smile on my face. Right now she’s talking about Paris, and something called a “flâneuse”.

“…Elkin is a fucking wrecker, you know? Neoliberal bullshit. Like, ah, wow, cool, neat, you just wrote Eat Pray Love for the CityLab set…”

We all laugh at that. Alan, sitting next to me, mutters with a glass to his lips, “… never read the Convolutes…”

I can’t tell anyone I have no idea what they’re talking about. I should be home, reading something relevant. Writing. The old panic of failure. These conversations always drain me. They get worse as the night goes on and the talk gets more theoretical. I know I can’t talk about the Book without these people. These are actual scholars. They would call me either insane or childish. I realize quietly that I’m not sure if they’re right, or just myopic — blinkered by some reality that is nonetheless irreal. What is the real difference between Benjamin and Hemmingen? Both are mystics, aren’t they?

I make an excuse to leave early, and come home to Book of the Arch. The cover seems to be glowing phosphorescent in the pitch black of my room.

I know I should be reading something else, something important. Inertia pulls me over to the Book and I randomly flip to a page toward the middle.

“When we call the mound-builders Cahokia,” Fatima expounds, “we are participating in a memetic anachronism, a flatline of meaning. As the French explorers themselves admit, the city had no name. Cahokia is a nominator applied retroactively; like the ghost lemurs of Madagascar, by the time the explorers found the poor souls sulking in the ruins of the city-without-a-name, they were only shades of their former selves. The Nameless City. And, ‘[w]hen I drew nigh the nameless city I knew it was accursed’.

If we must name it, let us call it the City of the Pyramids. To arrive at the City of the Pyramids requires a bridging of the gap. The City of the Dead is matched on the eastern shore by the City of Eternal Unlife. Despite his dissension, Hemmingen doubtlessly knew Choronzon must be superseded. The mound-builders also knew this, in a sense, because their quotidian was a state of constant supersession. They lived forever under N.O.X., the Night of Pan, that old, Old Night, wrapped in transcendent kairos.”

Old Night. I’m not sure what that means, exactly, but the name seems to imply… uh. Something more than just nighttime. I look outside. The blackness presses heavy on my window, deep and utterly impenetrable, telescoping unseen onto boundless infinity. Suddenly seeming tangible, not the absence of light at all but a sustained assault against the wan bulb overhead. “Unreverberate blackness”. What’s that quote from? Lovecraft? Ligotti? No no, none of those are right.

I make tea before falling asleep, hoping to head off an impending hangover. Ginger and chamomile wreathed in pallid steam. Another random page of the Book:

“William Burroughs’ intricate pseudo-Ægyptian cosmology points us to the West. His way, however is fraught, dependent on theoretical knowledge and lashed to the prow of narrative. Practically, Bartholomew constructs the door and Hemmingen draws back the Gate. Passage from the East to the West. Passage into St. Louis. Passage into the City of the Dead, the capital of Sheol.”

“… draws back the Gate.” The Gateway.

The Gateway to the West. The Arch.

Of course.

The whispering voice. Again. So far back in my mind this time I think I can hear it behind me. When I spin to look for the source I nearly fall over.

Fuck, get yourself together. You’re drunk, you’re hearing things, you’re concocting weird shit. Don’t go insane. Go to sleep. Wake up and try not to be a lunatic.

As I crawl into bed I blearily make a note to follow up on Peter’s friend from the Natural History Museum, the curator. Must make sure to email him tomorrow and ask for her information.

Sleep is restless. Bodies and faces flicker like a bad connection. The Book is a terror, sprouting tentacles, stalking corridors of dream. Rasping in the deep. It wears Hemmingen’s face, eyes black and burning.

Proceeding

The next morning I wake up and email Peter, asking after the friend who had initially recommended me the Book. Within seconds: mailer-daemon error. Address not found. No out of office, nothing.

After my morning class I look him up on the faculty directory. Another dead end — no results. The office phone at the end of his old emails is dead air.

He’s new, I remind myself. Probably just not fully in the system yet. I’ll try again in a few days.

The day is deep grey. Light rain. Bitter cold. In the evening, after class, I stand in the parking lot, my hand frozen, and watch the skyline preside over roaring highways, glowing hearthlike. There’s a knot in my stomach as I see the dull gunmetal parabola through the buildings and remember

Gateway

The Arch the arch the arch thearch the arch on the archon the horizon blazing black bleary burning in the distance

In the library, I pull Book of the Arch from my bag. On the first page my eyes again fall on Emily’s scribbled note and address.

Well, in the absence of getting to talk to Peter’s friend, Emily may be my best bet to get some answers. No email or phone number. Just address. It occurs to me that I could visit her right now. Just to see if she knows anything. And besides, I rationalize, if I stay here any longer, I’ll lose my mind.

The recently-passed rain has left behind heavy, iron petrichor, quickly becoming encased in ice. 1918 Division is only a few blocks away but the night air is so cold the yellow pools of light from the sodium streetlamps are frozen cones and hollow buzzing. My car whines, the synthetic leather of the wheel sticking to the heel of my palm, my fingertips. I park on Hogan, a small residential cross-street, and quickly walk down towards Division. At the corner, I stop.

A vast, fenced-in nothingness: 1918 Division doesn’t exist. There are no houses at all — just a metal fence, with a parking gate, stretching the whole block. When I cross to peer through the iron gate, I can see the back of a huge structure, a sulking behemoth of concrete panels dotted with sallow floodlights way across a dead parking lot.

The entire complex looks new, but not too new. 1918 Division, if it ever did exist, hadn’t been residential for at least a few decades. There goes my last attempt to find anything out about all this, I guess. As I turn away, I barely notice a shadowed plaque, mounted low to the ground, nearly hidden in the manicured brush. Embossed serifs gleam dully in the light. “Former site of Darst-Webbe Homes.”

Darst-Webbe? I know this one. It was one of Hemmingen’s housing projects, one of the biggest in the city. Demolished in the 70s, I believe. Had Emily been a resident of Darst-Webbe? Where was Emily now?

You mean when. This time the voice sounds just like it’s coming over my shoulder, muttering in my ear. I don’t even bother to look this time. I know there is nothing there I will be able to see.

Terra Form

I have barely slept when my alarm goes off. I head to campus to go to Olin, desperate for more info on Hemmingen, Bartholomew, anything. Realizing I’m getting a bit fanatic. Feeling strung out, exhausted. Huddle against the cold, raising trembling fingers to my lips to smoke as I walk from my car to the library.

Sarah is in the first floor — her usual spot — surrounded by a pile of books and paper. She gestures me over but I just wave back and continue on. I can’t stop right now.

The only sources on Hemmingen are Volumes 54-63 of The Handbook of Government Employees of the City and County of St. Louis, stored offsite, and almost certainly of not much use. There are 3 publications listed by Hemmingen directly, though. In the search results I can’t help but notice Book of the Arch does not appear as a source, which seems odd. A further quick search for Fatima Duré brings up nothing. Something to check back on later.

Hemmingen’s 3 articles are heterodox (to say the least). Though written on wildly different topics, and years apart they betray a deeper fascination with St. Louis esoterica than any rigorous urban planning subject, or really even his own profession as STLHA Director. The first of his works is an essay published in the Annals of the American Association of Geographers, Volume 43: “Stumbling Through the Ritual”. The second is in Cosmia Wandering — whatever the hell that is: “Social Trance-Formation: On the Empyrean Proceeding” and the last, published several weeks after his death in late 1963 in AAG 62, “A World Beneath Our Feet: The History and Continued Utility of the Cherokee Caves”.

The only one available is A World Beneath Our Feet, which I find tucked into the middle of AAG volume 62, itself sitting quiet and senescent, entombed in dust in an abandoned section of the stacks. Under the title, Hemmingen’s name is centered in the yellowing page, followed by a short, italicized epigraph: “…as Babalon above, so Babalon below.”

The essay begins:

“There is a massive cave system that underlays the downtown core of St. Louis, Missouri. This complex, known today by the marketing name ‘Cherokee Caves’, has in fact gone by many names and served many functions: subterranean chiller for breweries, a hub on the underground railroad, and most recently, a tourist attraction. But prior to the founding of St. Louis, these caves served as the fundament for the great imperial seat which the uneducated called Cahokia, but which truly is The Nameless City. And like the titular city in Lovecraft’s work, the Nameless City is, first and foremost, a grotto city, interred underground. The ruined mounds that the City is known for today are simply the surface literations of the large, sunken passages below. The mounds point down, not up, are the violent tip to a slumbering iceberg. The builders of the Nameless City understood they were holding territory. If one can undermine the enemy, victory is near at hand. And if one lacks the high ground, it can be manufactured. This is the true purpose of the mounds. Pyramids as war machines. Pyramids as monuments to the godforms of victory.”

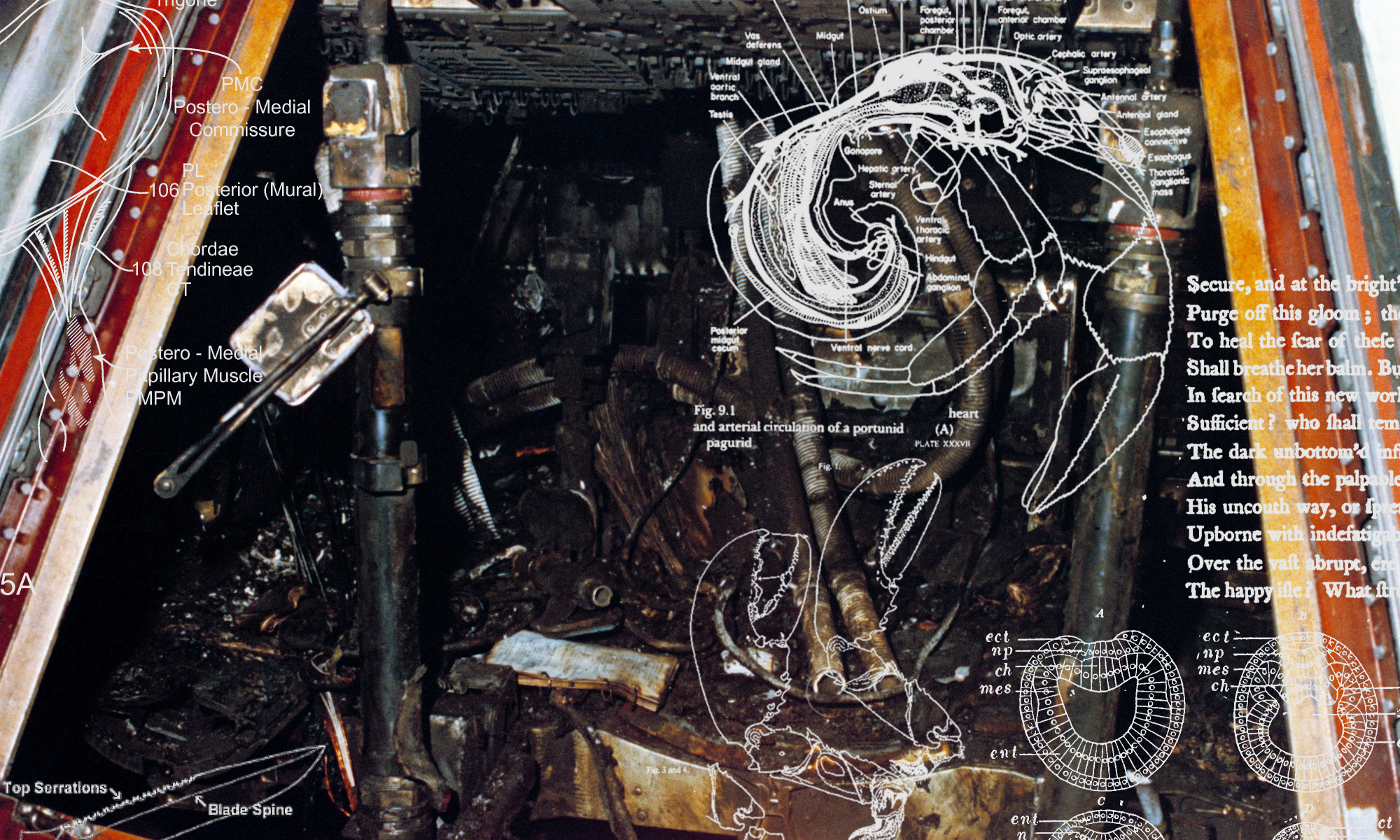

An inline map overlays the positions of the ancient mounds and known entrances to the greater cave network. The caption reads: “Map of the true city, out of sight, an arboreal cuidad lineal cut through solid lith.”

“Morphology of the Nameless City: rich villas bored into rock high in the main caverns, the poor sleeping standing up in narrow passages, dying early due to being forced to cook in unventilated areas during the constant states of emergency. The city presented its hidden face of indomitable stone as marauders ceaselessly violated the prairie overhead in great warbands. Long sluices through solid rock become spines of communication networks populated by chains of callers using the natural reverberating properties of the caves as a public announcement system to communicate information and coordinate tactics, lending their fast voices to the slow muttering of tectonics. By speaking with the Earth, the cave dwellers achieved an efficacy in the transmission of data that, to surface enemies, must have appeared nearly instantaneous. Hic et ubique?”

As I read on, Hemmingen’s argument is clearly well-researched, but absolutely delirious: As the population of the Nameless City began building up, the search for better real estate and scenic caverns led to a search further and further into the depths, the city complexifying as it ambled downwards, with elaborate and as-yet-undiscovered cisterns and agricultural construct machines. Pulling away from the surface together, going native in the bowels of the lithosphere, surface access essentially kept as a matter. The surfacemost points, according to Hemmingen, were left to become slums, being the most open to attack. These slums were “packed to the brim with the pitiful, seething dregs of the great civilization, those nearest the state of barbarity in which they’d be discovered later by the French”.

Hemmingen finishes this passage with a cryptic musing: “…as the elites of the City discovered in its course, the notion of a sacrificial mass of persons as a ‘buffer’ population definitely has its utility, a truism lost to history and the creeping humanitarianism of liberal socialism. This expendable mass functions as antibodies for the city, allowing mistakes without disaster, growth without bloating. They knew of the need for a prairie fire to sweep through society. The dross must be burned off.”

Further: “Apocryphal legend among the Shoshone peoples describes one such attack wherein a warband gained entry to the City. The only fatalities suffered by the attackers in their initial assault were three warriors who drowned in the blood of those they executed, after being pinned down by the deluge of those they had killed. The legend describes these wretched as too listless to fight back or even move. The elites, plotting deeper in their cave, were removed altogether from the violence, and thusly, allotted time to plan. When the Shoshone warriors finally burst into the cavern, having fjorded the insane flood of the dead they had created, the fighters of the elites were waiting there, and slaughtered them to a man. The city defends itself by sacrificing itself”

The paper ends with an omen: “The last extent entrance to the abyssal complex is due to be shut forever with the completion of the I-55 corridor, which follows the path of the original French expeditions. Thus the future shuts the door on the past. But the work of the mound-builders continues, as it is not done.

Their secrets will continue to be uncovered by myself and others. I have discovered what they only assumed, and confirmed it as fact; as such, I believe I can recreate and more importantly COMPLETE the centuries-old experiment.”

Finally, the essay closes with the words: “Keep your eye to both the East and the West. A new Proceeding has come.”

Dis-aster

“A new Proceeding has come,” Hemmingen says. For some reason, this phrase sounds familiar, reverberating off down catacombs of crumbling memory. From the Book, of course. Somewhere toward the beginning, if I remember correctly? It tumbles through my mind all day. After classes, I rush home and start to skim quickly through the pages, scanning feverishly. Within a moment, it abruptly it surfaces out of the torrent of text, at the end of the first chapter. Duré quoting Hemmingen:

“Two Oh Nine.

This will be my name at the completion of my Empyrean Proceeding, when I shall become other without losing myself.

Two Nine Zero is I;

Servant of Coph Nia,

Servant of Babalon,

Servant of the Starry Arch.”

The next paragraph is equally curious, containing a quote by “arch-itect and Grand Mason Saarinen” on what Duré calls the “holy form of the double wand”: “’…to achieve the simplicity of… the great pyramids of Egypt, because the simplest and purest forms last the longest, and I have always felt this arch of stainless steel would last a thousand years.’”.

“The form of the double wand, the form of the ARCH,” Duré continues, “is not just the Secret Gate, but is itself the toroidal Key unlocking the Sacred Hex. The peripatetic hubris of the obelisk, the arch, the towers, the mound, and yes, the key itself finds itself inverted in the transition from 1 to 0, from pyramid to Arch. In much the same way, one must derive from the Hex the symbol of Pisces in the way the method dictates: by constantly involuting, with appropriate rite. The way is thus: invert Pisces about its meridian, which must and will always remain true. The resultant alchemaic sigil is that of two arches; one above, one below; one celestial, one pelagic.”

Under this paragraph is a small note: “For the full text of the Proceeding to which this passage alludes, please turn to the Chapter called “Walking the Method”, at the end of this book.”

When I flip to the end of the book, looking for the extended quote, I discover the pages have been removed, torn out, leaving only their tattered remains still sewn into the binding.

Archive

I text Alan and ask if he’s at work. He works as an archivist at Olin, and I’ve had him help me with stuff before. I figure it’s worth a shot. He texts back a few minutes later that he’s at work and I tell him I’m coming up, looking for “a weird book”. After a few minutes, he responds that he’ll be there until 6 — sitting at the circulation desk. When I come in, I stamp off ice and snow, and he waves me back around to the small research area. Microfiche machines sag on tables and to the back of the alcove, a boneyard tangle of overhead projectors lying fitfully under a blown out light. As he sits down at the small, scratchy CRT monitor, he asks me, “so, you haven’t found anything on the book online?”

“Nope,” I offer, sheepishly.

“Well, I’m sure that means it’s very hard to find,” he says with what I’m sure is a self-assured air. “What’s it called again?”

“The Book of the Arch.”

He turns back to me with an eyebrow raised. “Weird title.”

I shrug. “I guess.”

He begins with a digital search in the University databases. Nothing. The keys chatter like insects under his fingertips as he makes multiple attempts, all dead-ending. Finally, he says, slightly exasperated, “you weren’t kidding about it being hard to find,” and moves over to the microfiche. A few minutes with his eyes buried in the catalog, he breathes deeply and leans back, clasping his hands behind his head.

“Fuck, man. This book may as well not exist,” Alan says, squinting hard at the ceiling. “Well, let me take one more swing at it. Wait a minute.”

He starts over on his circuit, but deeper this time. Repeated searches in multiple databases, at multiple libraries. After several minutes, he turns to another computer. He grimaces and says, “it’s time for the nuclear option” as the computer screen goes white and starts humming. After a minute, he turns the monitor to me, which has a single link:

Did you mean: Liber Arcus?

“I’m not even really sure what database this is pulling from. This computer got pulled up from the basement last week,” he muses.

“Can you click on the link?”

When he does, an ancient webpage appears, deep maroon on black. The masthead reads VYSPAROV DIGITAL COLLECTION. In the middle of the page is a spinning wheel and text which reads “contacting database…”

“Ever heard of Vysparov before?” I ask. He nods no, he hasn’t.

Finally, the database entry on this Liber Arcus loads in:

“The Liber Arcus is a late-medieval codex of unknown provenance. Only one copy is known to have survived, but sadly with a good amount of the original pages lost. The Liber Arcus was previously housed in the Vysparov collection, and prior to that was located in the Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana.”

“Don’t think we have ILL access with the Vatican Archives,” Alan says.

“The text has been the subject of much debate over the years due to its obscure subject matter; it describes in detail a City of the Pyramids (Pyramidum Civitas) and the coming, or rather summoning, of some unknown apocalyptic event using the form of the city itself. Some early scholars claim it is the first dystopia, predating the heyday of the Renaissance utopian imaginary by hundreds of years. The text is said to have been written by an Ottoman beatus, identified alternatively as Lecta or Lucta.

[NO DIGITAL COPY AVAILABLE]

The only extent copy was purchased in 1952 by an anonymous buyer on behalf of the Harland Bartholomew & Associates Private Archive, from the Vysparov Collection. In 2008, it was gifted to the Library of Washington University, where it remains to this day.”

“Huh,” says Alan, after reading the last line. “Private archive, huh? That’s usually not indexed — must be why it didn’t show up on my first search.”

“Can I read it?” I ask.

Alan stares at me, blinks, laughs. “Oh, I doubt it. No way, actually. Not officially. The HBA archive is basically closed to anyone that isn’t a relative of Bartholomew himself.”

I press my luck. “Could you get me in?”

“No chance. But, uh…” he looks around conspiratorially, “Well, maybe. But only for a few hours. Would that even be worth it?”

I nod yes. “I could leave the keys out tonight,” he says. “But we’ll have to make a plan.”

It quickly comes together: tonight, when Alan locks up, he will leave the skeleton key to the basement archives on his desk in his office, underneath a file folder. The door to the wing of offices is 8430. The private archive rooms are in the basement, and are all protected with simple, ancient locks. No cameras, either. When I’m done, I’ll replace the key in his office.

I thank Alan and go to leave. “Come back late as you can”, he says. “There’s night security, but they do the rounds for the whole campus. They usually start in here around 2 and then walk around.”

“I’ll be back at 3,” I assure him.

“You must really need this book, huh?” he asks. I have no answer.

I go home for a while. I take a fitful nap and wake up sweating. The weather has shifted. The previously frigid wind seeping in through the half-cracked window has been replaced by a noxiously warm breeze that almost surges and falls like breathing. I’m feeling haunted and anxious again, trying to identify anything out of place. When I roll over, I realize Book of the Arch has been lying facedown next to me, and Fatima’s face is staring out from the back cover. Her previously benign smile now seems gnomic, sinister. I throw the book in my bag. It’s been years since I took Latin, but I still have my translator’s dictionary, so I throw that in too. When I check the clock it’s 2:30 AM.

The library is quiet, looming, its highest stories plunging into a shroud of fog. The windows are too harsh and bright against the black, too ineffectual. Old Night. My stomach is churning acid.

When I look out the third floor window across the windswept vacancy of the campus, I can see the black security SUV with its lights pinched again the gloom. Inside, there is no light except for the periodic wink of fire alarms from between broken-toothed stacks. The white-glass door on the east wall is right where Alan said it would be, and when I enter the passcode it whispers open with a sigh. The key hidden on his desk is a bizarre, ancient thing — black iron with teeth gleaming predatory in the dull light from the hall.

At the end of the hallway containing the offices is a small back of house elevator, leading down to the basement archives. As I descend, I run through Alan’s description: “The basement is kind of strange. It used to be one huge room back when it was originally built. You’re looking for an door with old, black wood and a brass knob. The only one unmarked. White plaster, butted against the southern wall…left if you’re coming out of the office elevator. Once you get inside, there’s a single bulb overhead, with a pullstring.”

The elevator opens onto deep blackness. Within the cone of my phone light, I catch disordered stacks of paper lining the walls and jutting into the corridor, sedimented into stacks or spilling from banker’s boxes, forming a labyrinth. The air is still, deadened with the smell of mildew. When I find the black door, I slip the key in as quietly as I can. Afraid of disturbing something. As I turn the key, tumblers in the lock rise and fall like a ragged breath then thud home. When the door opens, the stench of rot sweeps out, so strong I nearly gag. Feeling in the dark, I find the pull string for the light overhead, and the bulb flickers on resignedly. The ashen light illuminates stacks of books and rolls of drawings, all spilling out of gridded wood shelves that rise to the ceiling. In multiple places the shelves have collapsed, producing cascades of paper, plastic slipcover, and canvas binding. The center of the room is dominated by a massive wooden table, long dulled with dust and raked with fine cuts, its surface completely empty. As my eyes adjust, I notice a black mass in the back corner of the small chamber, seemingly alive. As I move closer, curious, I can make out within its folds words, inscriptions, drawings. When it’s nearly a foot from my face, I put it together: this is the source of the smell. This sinusoidal thing is a colony of black mold, quietly feeding on papers, drawings, diary pages. It is nearly as tall as my knee.

I gag again, and vomit this time for good measure. A horrendous image comes to mind: in a few decades’ time, another person coming to the Bartholomew Archive, opening the door only to be greeted by an impossible wall of obsidian hyphae, the organism having feasted on the entire of Bartholomew’s knowledge, eating what remains into obscurity.

I imagine cutting it open for Bartholomew himself to tumble out like a botched Caesarian.

I can’t stay here long, with this thing. I just have to hope that catalog entry was right. As I flit my fingers over burst shelves and sift through aged sheafs of paper. A schizo library. 1907 Proposal. Notes for 1947 Master Plan. The dismembered spine of an enormous book, faded gilt lettering reading Irem: City of Pillars by Al-Hazred. An enormous column of pages curled with water damage, identical ink footers reading AN ENGINEER’S REPORT. A flurry of identical notebooks dusting everything, their bindings long gone.

On a high shelf near the door, sitting on yet another caved-in stack, is a small black lockbox, violent with intensity. Its lid is dented and scarred, the hinges burst. I pry it open to reveal a small, black book, eating the light. On the aged cover, subtly inset, is a title.

The Liber Arcus.

The words are barely legible. A few stragglers of gilt inlay, the bulk of it long gone, are embedded in the fibers of the canvas. The book itself is small, thin, somehow emaciated. I realize now I had expected something huge, tortured, covered in faces of demons and…well, god knows what. A massive necronomicon, bound in human skin or something like that. The book seems to be immaculately preserved, with thick cord holding the pages together. When I pick up the book, a small slip of paper flutters to the floor, text printed on one side. Set in a simple border is a typed message:

“The ESTATE of LOUIS HEMMINGEN bequeaths the contents of this box to the WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY of ST. LOUIS, MISSOURI for eternal inclusion in the private archive of the LATE HARLAND BARTHOLOMEW and his ASSOCIATED, with the knowledge that there will come a more enlightened Aeon find themselves under the EMPYREAN ARCH, and the KNOWLEDGE contained within shall be freed and forthwith GIFTED to the NEW MAN.”

So Hemmingen is the “anonymous buyer” that purchased the Liber Arcus from the Vysparov collection. Of course.

Under the Liber, in the bottom of the box, is a folded-over polaroid of two men, one seated and one standing, in a small drab room. On the back, in Bartholomew’s slanted script:

Auspicious convening of Church of Starry Wisdom. 1950.

Bartholomew is seated, pointing at a map unfolded on his desk, with Hemmingen watching intently. The map is covered in markings. Stars, blocked-out areas, and heavy scarring — gashes on the landscape, etched with frantic intensity. But underneath the markings, it’s inescapable — St. Louis, sitting inside the gentle curve of the Mississippi.

I sit down at the long, low table in the center of the room and set the Liber Arcus before me, along with Book of the Arch and the translator’s dictionary. The frontispiece of the Liber is a drawing of a woman under an arch made out of stars in the night sky, the symbol of Pisces seated at the crown. She walks on a concave sea of flames.

CAPITULUM I.

“Ob motum gentium perveni ad vos.”

This one is easy to translate: “For the movement of peoples I have come to you…”

The first line of the Book of the Arch…

I look at the cover of the Liber and shiver uncontrollably. Air suddenly gone ice cold. Just like I did when I first held it. What is this thing? What is Emily’s copy of the Book? The thing is rotten with time, a prison break note from outside history.

Heart racing, I flip to the back pages of the Liber Arcus, those missing from my copy, hoping to find an answer. The missing pages seem to be intended to be read together, one line each set dead center of the 7 pages. I feverishly translate them word by word, and transcribe the english onto a nearby scrap of paper. When I’m finished, I read it back aloud, my voice cracking in the entombed squalor:

- I am BABALON. The word before was true, but improperly spoken. I am COPH NIA, that of RA-HOOR-KHUIT.

- My PROCEEDING is in the gathering of the child. The child is multiple.

- My wand shall be completed. The wand is the PASSAGE, a canal of divine birth.

- The Empyrean path works in TRINITY. Look ye both above and below, heavens and hells. I shall bring ye up from them, and also down.

- I will PILGRIMAGE for ye. Prepare my resting place. My home is inside the inversion. My consummation is in A Blessed Mirror.

- Only I am enough this time, as it always was. My SIGN IS THE STAR. Look to the East and also for its passage in the boundless.

- Call my name BABALON and know the sundering of the AEON is at hand.

I get up from the table fast, my breathing frantic, overcome by blinding panic. Breath visible in the air. Everything feels wrong. Deep in the turgid pit of my stomach, something has changed. These were not just words at all, but an incantation. The light flickers overhead, allowing shadows to swamp the room for a moment. When the light comes back, a shifting by the black body of the bibliophagic mold draws my attention. Something in the world, something secret, has been overwritten.

With my fear overcome by curiosity, I investigate the mold again. Dying to know. Whatever change that entered the room when the lights went out is centered here. I know it.

After a moment, I notice a crushed, rolled tube of paper I don’t remember being there before. Its edges are torn, and the surface printed with something dark grey, mottled. I’m drawn to it. I pick it out of the drift of papers, inches from the advancing mold colony, and retreat to the table to unroll it.

It’s the map. The same one from the photo in the box of the inaugural of the Church of Starry Wisdom. The one on the desk, on which Bartholomew is drawing. But this map is just a 1950s satellite photo of the city, no drawings on its aged surface. The edges are dirty, torn.

Suddenly, the whole room seems to sigh, and I know I am not alone. But instead of rising, my anxiety vanishes, replaced by a resigned stillness, a divine hush.

Unroll the map on the table and follow. I will guide thee.

At peace.

Walk the incantation.

The Voice. I allow myself to be lead, my body and mind under some type of soft duress, responding to both my own commands and those of the alien Voice.

- I am BABALON. The word before was true, but improperly spoken. I am COPH NIA, that of RA-HOOR-KHUIT.

Center thyself. This is a greeting from the hopelessly beyond, the Bound Infinite. An announcement of unbirth.

- My PROCEEDING is in the gathering of the child. The child is multiple.

The children are the dead, the sacrificial, the chattel for slaughter. Hemmingen’s projects, the public housing. Mark the towers with the sign of the star.

- My wand shall be completed. The wand is the PASSAGE, a canal of divine birth.

The wand is the Arch, doubled and joined. A canal of life into death. A tube of fire. A resplendent exit. To the West. Signify it with a line.

- The empyrean path works in TRINITY. Look ye both above and below, heavens and hells. I shall bring ye up from them, and also down.

As Babalon above. The stars. So Babalon below. The caves. So Babalon in the meridian. The city.

- I will PILGRIMAGE for ye. Prepare my resting place. My home is inside the inversion. My consummation is in A Blessed Mirror.

The Pilgrimage up from below. The old explorer’s corridor. I-55. The Arch, the double wand. Doubled again by its reflection in the Mississippi. Trace the river with a line. Complete the sign of Pisces.

- “Only I am enough this time, as it always was. My SIGN IS THE STAR. Look to the East and also for its passage in the boundless.

The Morning Star, the Fallen, traversing to the West. To the East is the Nameless City. Passing into Eternity through the gate to the West. The passage tracing the Starry Arch both in the firmament and below. The conjoining of the syzygetic pairs. The Nameless past to the aborted future.

- Call my name BABALON and know the sundering of the AEON is at hand.

The birth is the death. Passage through the gate draws all of reality with it. The Axis Mundi, centered at the Arch, at Saarinen’s Pyramid, cracks and screams. The sky weeps black ichor at the end of the Age.

Still possessed of the same resolute quiet, I look at the map. All of it is centered, spinning on the Arch. A geographical sigil. What had Duré (or ‘beatus Lecta’) called it? The toroidal key to the Sacred Hex, the involuting center of Hemmingen’s thaumaturgy. I realize the Arch is not just a gate to the East and West, I realize, but also above and below. A 90 degree revolution. Or rather, it would have been, had Hemmingen completed his task.

You must complete it. And I know, again, the Voice is right. Why, I don’t know. But there’s no argument I could raise against it, or rather against myself. There was never any difference anyway.

Close the circuit, I whisper into the library-crypt. But how? Hemmingen had said the construction I-55, in completing the lower arch, had sealed the last public entrance. Follow the stars. He was intentionally being misleading, covering his tracks. To the towers. To the undercity. In the bones of the towers, in the sealed bowels, I know, beyond the shadow of a doubt, I would be able to find a way down to lower Babalon.

1918 Division. “Former site of Darst-Webbe Homes.”

Night-side

Arch forever on the horizon, a thin carving of steel against the night sky. The world barely breathing. When I arrive at 1918 Division I park hurriedly and slip the reproduction of the Starry Wisdom map in my back pocket.

At the gate, I jump the fence and break into a run. Straight ahead, the ground sinks to a drainage pit. At either end, the outflow sewers are sealed shut with grates, so I start to dig. With a rock, I scrape at the top layer of still-frozen mud at the base of the pit. It begins glassing off in shards. I keep going until the ground softens, and the rock loses its effectiveness. Undaunted, I use my hands to shovel out black earth. Any second. I can feel it now: the hollows below, singing in my blood, calling in the depths.

With a soft moan, the ground around me cracks and caves in, and I fall with the dirt and rock into a small subterranean chamber. The moonlight pools over the concrete walls and floor, sagged and shifted, open cracks with dirt pouring through. The ceiling, where it still exists, is covered in moldy, rotted insulation that sloughs in great sheets like sheaths of skin, revealing crumbling metal beams. An ancient water heater, nested in an impossible tangle of piping, sits in the corner on a ruinous concrete plinth, listing horribly to one side. An old laminate table, 3 legs buckled and the top cracked in half, is lying in the middle of the floor. My shoes crunch dead shards of glass when I walk. I check — yes, the map is still in my back pocket. A single metal door, the frame warped and burst, sits in the shattered wall. Red block letters painted on the cerulean face say WARNING. The door is cracked slightly, dust on the floor saltating in the jet of air exhaled from beyond. I make my way across the room and throw the door open fully. Further in and further down. A thin stair, built out of the same devastated concrete as the floor, projects into the darkness, bending gently right as it disappears downward. The walls are earthen, but poorly trammeled, and small tumbles of earth have calved off into piles that scatter down the steps. There is a great, ragged respiration coming from deep inside the abyss, sallow and distant. It is only now that some part of my basal brain rebels, terrified of the Night beyond the door, howls at me to turn back.

I step forward into the blackness anyway, guided by the Voice.

There is no light but I feel along the walls, rotating ever left, stepping carefully. After a minute or two, a pale, green glimmer blooms beyond the curve of the wall, not exactly illuminating so much as throwing what had been hidden into hypersaturated relief.

When I reach the last step I have arrived in not a chamber, but rather a narrow channel, only wide enough for me to advance sideways. The green light is coming from everywhere and nowhere. The walls are solid rock, slicked with dampness. I run my palms along the smooth surface.

Halfway through the passage my steps are accompanied by crunching, chittering noises. When I look down, I can just make out my foot. Next to it is a staved-in skull, not bleached white but pocked with viscsera and gristle. Looking ahead are countless more skulls, ribs, and other bones, heaped in messy tangles. When I draw my hand back from the wall it’s covered in viscous oily blood, unmistakable even in the green phosphorescence.

Forward. Doesn’t matter any more. The way out is through.

The majority of the bones scatter to dust when I disturb their careful assemblages. Every inhale paired with a cough. Finally, as the passage opens, the graveyard thins. The vibrancy of the claustrophobic green fades to a watery ambience, less defined by green then by a yawning black.

When my eyes adjust, I can see the cave has expanded into a massive cavern, the bulbed ceiling overhead upheld by immense knarled pillars of rock that recede into blackness. From below they reach down like the tentacles of some hideously aged god. One of these, a massive stalactite, hangs to my left. Its drip-drip-drip sounds off seconds in the vast hollow, reverberating down unseen chicanes. I catch a drop in my palm and note it is also blood, squirming in my cupped hand.

I walk deeper into the cave. Away from the surface, into the involuting complex. The Voice narrates to me from inside my own head a vision of history collapsing on itself — the caves open to the air, swallowing St. Louis whole, plunging it back through history into deep time. Digging down is time travel. The open cave is a broken loop, a paradox. I can see it as it speaks: highways dragged like choppy ribbons across bottomless chasms, the Mississippi delicately pouring itself into the warrens over a rocky lip. The whole complex, slowly filling the entire to diluvian completion. Never mind the work will take centuries.

Hearing the Voice speak of ruin gives the devastation shape. In burst open concrete, hypnogogically perfect, I can read sedimentations of hatred like tree rings, Hemmingen’s strata being the darkest color of bile, but also ending furthest from where they began. The hideous rocketry of malice. The bowed floors of downtown towers close like a book on fate. I point myself out from the looping turbulence, poised at a fulcrum, or maybe an eye. As remote from the future as the Nameless is from me. Walking on the cavern floor is to ambulate through the once and future ruin of empire, walking a tightrope along an unbroken continuum of ruin that extends forever. Hemmingen’s landscape. The revolt of the caves. Revolve around the toroidal key. Heaven becomes hell. The whole world a sacrificial population.

Even more than Bartholomew, Hemmingen had found a comrade in time. An engine of will. A shaper of a black current. Stick the key in and break it off. The Voice says: It is only in making oneself a disciple of total dissolution, by waging jihad on form itself, that one can see their work completed. Tesselation is hubris. To design, to plan, is to fail: the only success is in making oneself a part of the slavering mob of time that is always waiting patiently. An architecture of patience. The entropic assault is at the gates: in the lost neighborhoods of Old St. Louis, boarded up houses sag to pieces and century-old bricks shatter in the wall.

All Hemmingen was doing in completing the work of the Nameless was inviting the utter nullity of Outside in, warmly, like an old friend.

Here in Babalon I am home. Passed through the Gate of the Secret. The Secret is the End. I know I will be meeting Peter here, soon. And Emily, and Sarah, and Alan, and everyone else.

The whole city will come down to me. Hemmingen did not fail because he could never succeed: the human cannot become the agent of the inhuman. All Hemmingen could do was identify and organize the process, and leave the rest. Time itself will happily take up the yoke. Coph Nia, the weeping mother, postpartum Medea, waiting at the end of the line. Weary and battered, drowning time in the bathwater. The Aeon will sunder on its own, and St. Louis will drift down and apart, sinking quietly into the soft alluvial mud, until this cavernous, rocky womb bursts open to once again accept its child.

Born of violence and dead of quietude, just like all the cities that had come before.

All there is to do now is wait.

One Reply to “Gateway to the West”